The US has a tart cherry problem. Amy Iezzoni, professor emerita at Michigan State University, is trying to change that.

For many people, tart cherries only come to mind when it’s time to fill a pie crust. For Amy Iezzoni, tart cherries are everything.

Iezzoni is the only institution-affiliated tart cherry breeder in the United States. And if you’re going to work with tart cherries, Michigan is the place to do it. Michigan is the leading US producer of this fruit, accounting for 75 percent of tart cherry acreage.

But if Michigan has a tart cherry abundance, it also has a tart cherry problem: The industry is dominated by one type of tree. The Montmorency cherry originated in Europe, and today, it is the main commercial tart cherry in the US. Most of the tart cherries you’ll find at the store—often in cans or in the frozen food aisle—are Montmorency. The lack of diversity in the tart cherry landscape has made growers vulnerable to threats such as disease, pests and climate change.

It’s a problem that Iezzoni has been addressing for her entire career.

Amy Iezzoni, professor emerita at MSU. (Photography courtesy of Amy Iezzoni).

Plant breeding is how we get the optimal versions of our favorite foods—the corn with the biggest kernels, the crispest apples, the tomatoes with the ideal shelf life. Breeding also gives us more options from which to choose.

Hybrid breeding is the process of crossing two varieties of something to create a new cultivar that has traits of both parents. It can take a few generations to stabilize the results, and it traditionally requires a lot of trial and error.

When Iezzoni was an undergraduate student at North Carolina State University in the 1970s, she got to work with a peach breeder. It was working with peaches that set the course of her career. Fruit, she says, had not made the same progress in breeding science as bigger crops such as vegetables and grains.

“I felt that I could make more of an impact—more of a change that consumers might actually see and benefit from—by working on fruit because it was rarely done,” says Iezzoni.

In 1981, Iezzoni was hired by Michigan State University as a tart cherry breeder, the first of her kind there.

“I didn’t inherit a program because there was no real program,” says Iezzoni. “There was really nothing to change; there was something to develop.”

Iezzoni was tasked with building a breeding program from the ground up. But there was a problem: She needed access to cherries that weren’t Montmorency.

“You need genetic diversity to make a breeding program,” says Iezzoni. “There are certain traits that the industry wanted bred into new cultivars, and if you don’t have the diversity to do that, you’re sort of stuck.”

So, Iezzoni went to where there was a diversity of tart cherries, which just happened to be behind the Iron Curtain. In 1983, Iezzoni traveled to several Eastern European countries in search of tart cherries beyond Montmorency. Iezzoni collected pollen samples, brought them back to the US, and began putting them to work immediately.

The first step was to infuse the breeding program with Eastern Europe’s cherry diversity. Having more options in the industry is not just a resilience tactic; it can open consumers up to a wide range of possibilities when it comes to the flavors and uses for cherries.

Cherry blossoms at the MSU Clarksville Research Center. (Photography courtesy of Amy Iezzoni.)

“Think of the apple industry with just Red Delicious,” says Iezzoni. “How many Red Delicious would you eat? There are cherries that are as different as Red Delicious is from Honeycrisp.”

The next aspect of the work was trying to optimize some of that genetic diversity to address the main challenges in the tart cherry industry. From her test orchard in Clarksville—25 acres of diverse cherry trees—she began breeding to address the primary threats.

Among the leading issues Iezzoni has worked on are cherry leaf spot (an infectious fungal disease) and spotted wing drosophila (a fly known for infesting and damaging certain crops). Iezzoni also focused on breeding for later bloom time. Warmer temperatures associated with climate change can prompt cherries to bloom earlier, but that makes them more vulnerable to late spring frosts. Michigan’s tart cherry industry saw huge losses in 2012 due to spring frost. Future breeding to address these obstacles will depend on the critical work done by Iezzoni.

Cherry trees at the MSU Clarksville Research Center. (Photography courtesy of Amy Iezzoni.)

The breeding process is long and slow, especially when it comes to fruit trees. The lengthy juvenile stage means that many years pass before you start seeing results. One thing that can speed it up? DNA. Having genomic insights can help breeders hack the process, by knowing what genes are associated with the traits for which they are breeding.

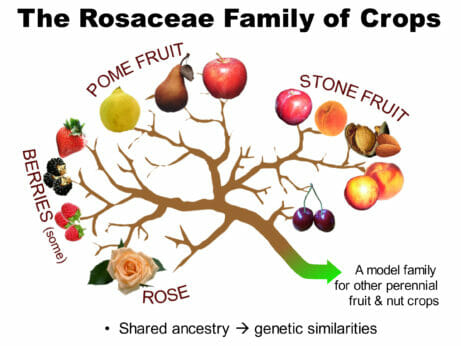

Iezzoni was awarded USDA funding to start and run RosBREED, a project intended to develop DNA tests and breeding strategies to create new cultivated varieties for eight different crops within the Rosaceae family, including tart and sweet cherries, apples, peaches and strawberries. Beginning in 2009, the project involved dozens of scientists across research programs.

Last year, Iezzoni was part of a team of MSU researchers that created the first annotated genome of the Montmorency cherry—a tool that will unlock a lot of doors for the future, not just for tart cherries but for other Prunus crops such as peaches and apricots, as similarities in the DNA can be used to speed up discoveries.

“I wanted to leave the program having crossed that hurdle,” says Iezzoni. “And so having done that is really good closure for me.”

The Rosaceae family of crops. (Graphic courtesy of Amy Iezzoni.)

Iezzoni officially retired in August of 2021, but she has been “keeping the lights on,” she says. Iezzoni wants to get certain cherry cultivars into the market, even if it’s just a cherry tree here and there, in peoples’ backyards.

“If I can just get to the point where they’re tested, and then I can get them in commerce,” says Iezzoni, “then that’s my goal.”

Even in retirement, Iezzoni retains her passion for tart cherries. She remembers a breeding class coming out to the Clarksville orchard. She let the students pick both sweet and tart cherries and take home whatever they wanted. Nearly everyone, she says, opted for a tart cherry variety called Jubileum.

“Who would have thought people would choose a tart cherry over a sweet cherry?” says Iezzoni. “You can’t even fathom that—until you taste it.”

The Morello cherry is the prized tart cherry in my native country Turkey.I am wondering if its unique flavor has found its way into Dr Iezzoni’s hybrids.

Love tart Cherry jam made with Montmorency cherries from France.