Will Bonsall’s collection has dwindled since its peak.

Over the years, Will Bonsall’s seed saving operation has been in flux. At one point, it included up to 5,000 different varieties of peas, potatoes and countless other crops that gardeners and farmers could request samples of.

Today, his collection has dwindled to just a few hundred varieties, as he has struggled with a lack of funding. Many of the seeds he’s stashed on his shelves over the years have died. Every year, more die, but the 71-year-old homesteader is still hopeful he’ll be able to revive his project with reliable funding.

“I want to be free to die and know that this stuff will continue on,” he says.

Bonsall launched his Scatterseed Project on his farm in Industry, Maine in 1981. In the early 1990s, Bonsall helped form a network of seed curators funded by the Seed Savers Exchange, an Iowa-based organization that looks to preserve heirloom varieties and facilitate seed sharing. Bonsall was one of a handful of seed savers across the country tasked with keeping certain varieties alive, and was in charge of some of the larger collections, such as biennials and potatoes. His funding was pulled almost ten years ago and his collection has struggled since. He now relies on limited grants, donations and fees he charges for seed samples, but it isn’t enough to hire the workers he needs to help.

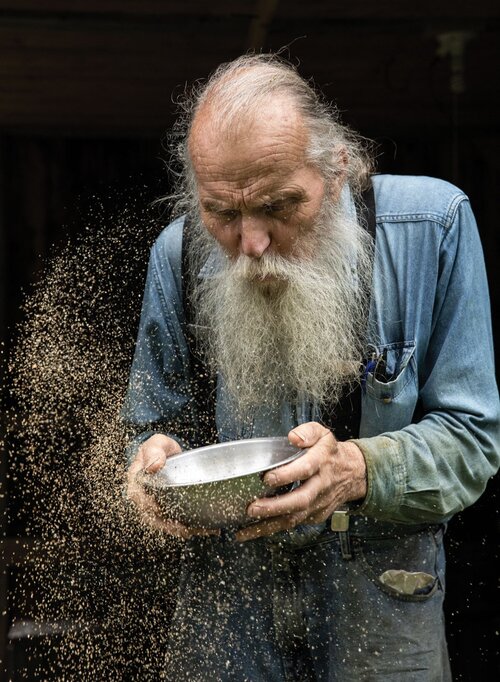

Bonsall grows his own food on a plot near his home, and has set aside two separate plots, whose sole purpose is seed saving. Any food he gets from those additional plots is incidental. He has gained a reputation for saving rare heirloom seeds and boasts what was once a world-class collection of rutabaga seeds.

When the vegan farmer first started saving seeds, he didn’t think much about the fact that certain varieties might need to be preserved because they were rare or endangered. His primary interest was saving them so he could be self-sufficient and grow all of his own food. Since then, he has come to recognize the important role seed saving has in preserving plant diversity and warding off famine.

“Our lives depend on it. If we want to eat, [genetic plant] diversity is the cushion. It is the buffer between plenty and starvation,” he says.

Bonsall believes the most sustainable places to conserve that diversity aren’t in public seed collections, such as those run by the USDA, but in the farms and gardens of America. Only 6 percent of vegetable seed varieties listed in the USDA’s seed inventory in 1903 were still available commercially a hundred years later. Bonsall blames this on the fact that food production has been consolidated and moved away from local farms and gardens. He says these places are the best places to preserve seeds, as the farmers and growers working in them have an incentive to grow these crops year in and year out and don’t depend on government budgets, which can be cut suddenly.

Bonsall says he doesn’t “sell” seeds in the way a seed company does, as he doesn’t offer pounds and pounds of a certain variety. He simply shares samples for a fee. He compares the difference between his operation and seed companies to that of a library and a bookstore. Seed companies are focused on selling varieties that are in high demand. His function, however, is to hold onto everything, as a library keeps books. “Do they get rid of it? No, their job is to keep it there,” he says.

While most of Bonsall’s seeds are lost, he believes he can retrieve most of them from his original sources and those he has shared his seeds with over the years. He has helped set up a new small organization called the Grassroots Seed Network, where he has listed some of his seeds. He is confident that if he can secure some reliable funding, he can come surging back to reestablish and even expand his collection. But what’s really important for Bonsall, is that the diversity of seeds within the collection lives on.

Were losing our farmers to old age, step up young ones and find a mentor before their all gone. Remember their wisdom is not on the web!!!!

Mr. Bonsall’s endeavors certainly seem worthwhile, but I’m afraid his business model seems lacking. He’ll need to figure out a way to bring sustainable revenue, or obtain consistent funding from government or foundation sources. Otherwise it seems that this project will go by the wayside when he does unfortunately.

To be quite honest,it seems he just needs human contact and support,help with basic stuff-like sending emails; crowd funding for couriers,some volunteers to build safe places for the seeds-real ,basic non rocket science being there reliably help?

Your article is not only fantastic but it is well-written as well….Much appreciated..

So, a guy relies on grants from others and then blames a lack of free money for biodiversity loss