One of Japan's top stem cell scientists is on his way to California to use pigs as incubators for human organs. Is the U.S. ready?

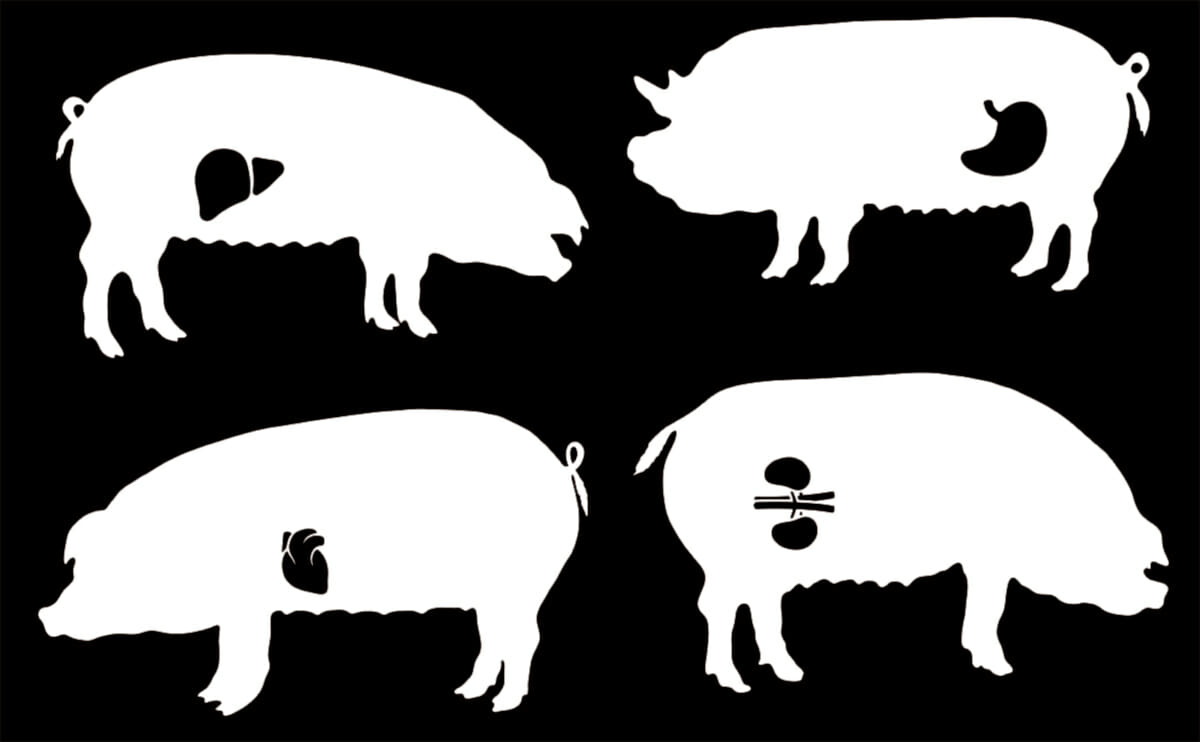

Over the last decade, Prof. Hiromitsu Nakauchi’s research at Tokyo University has shifted that question from science fiction to the agendas of government panels on bioethics. On one side of the debate, scientists see a near-endless supply of organs for patients awaiting transplants. Yet to get there, society would have to accept an image many find unsettling: farms full of pigs that, at a cellular level, are part human. Many bioethicists rank their queasiness in direct proportion to the humanity of those pigs.

“Should our worries about a Brave New World overwhelm something that would be incredibly useful and cool?,” asks Christopher Thomas Scott, PhD, Director of Stanford’s Program on Stem Cells in Society, Senior Research Scholar at the Center for Biomedical Ethics and now a colleague of Nakauchi’s.

So far, Prof. Nakauchi hasn’t made any pigs with human organs, but he has perfected techniques to make creatures that share cells from two genetically distinct sources. Scientists refer to those animals as chimeras, like the fire-breathing goat-snake-lion combo of Homer’s “Illiad,“ but outside of mythology, chimeras are rarely monstrous. Scott says anyone with a pig’s heart valve or even a bone marrow transplant is technically a chimera. Strange cases of chimeric people with two DNA profiles — the result of a rare fusion of two fertilized embryos in the womb — also litter medical history.

In order to harvest human organs from pigs, society would have to accept an image many find unsettling: farms full of pigs that, at a cellular level, are part human. Many bioethicists rank their queasiness in direct proportion to the humanity of those pigs.

In his Japanese lab, Nakauchi’s team has learned to develop chimeras with much greater precision using embryonic or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Of the two types, iPS cells have particular promise because they can be derived from a patient’s skin or blood, opening the possibility of pigs not just growing any pancreas, but your pancreas. Transplants have a much higher chance of success if the organ matches the genetic makeup of the patient.

Here’s how it works, according to Science Daily: The team inserts stem cells into an embryo that has been genetically modified to not grow an organ (say, a pancreas), then plant it into a surrogate mother. One gestation period later, a chimera emerges with the body of the embryo donor and the pancreas of the stem cell donor. Variations on that basic technique have allowed Nakauchi’s team to create a mouse with a rat pancreas in 2010 and a white pig with the pancreas of a black pig in 2013.

So why stop short of a pig with a human pancreas? From a biological perspective, having a pig host human organs is trickier than swapping body parts between two pig cousins. In comments to the BBC, Nakauchi said he wouldn’t expect such a success for at least another five years.

But in Japan, Nakauchi’s hopes were also well ahead of the law. A Japanese panel on bioethics recommended the country lift a ban on certain experiments combining human and animal cells at Nakauchi’s behest last July, but not before the promise of funding and laxer oversight had lured him to Stanford.

Now, Americans are going to have to assess their feelings on a farm animal becoming an organ farm. If history is any indication, it won’t be pretty.

In 2005, Republican Senator Sam Brownback — now the governor of Kansas — introduced legislation that would have sentenced scientists experimenting with human stem cells in chimeras to 10 years in prison and a million-dollar fine. Thomas Scott at Stanford says the legislation was so harsh and vague it politicized the issue, leaving the U.S. free of federal laws governing experiments with chimeras.

That doesn’t mean the research is free of concern or oversight. On a biological level, scientists want to be sure the experiments don’t create pigs that are perfect incubators for human disease. And for ethicists, there’s a far weirder question: At what point would a transgenic pig need to be considered a person? As Scott points out, ideas of what makes us humans human go deeper than a cellular census. People think, feel and talk. Even if a Dr. Nakauchi could make a pig with a brain made of human neurons, that pig probably wouldn’t introduce itself as Porky. That might be less true for animal that shares more of our neural architecture — chimps, gorillas and the like.

“So they are going to act like pigs, they are going to feel like pigs, whatever ‘pig-ness’ is,” says Scott. “We don’t know. We are not pigs.”

Even so, guidelines from the U.S. National Academies’ Guidelines for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research flag any experiments that could mix human cells into a chimera’s brain or germ line — the genetic material it could pass onto an offspring. Those rules impede the Sci-Fi Channel scenario of a conscious pig or a pig carrying a human fetus.

“So they are going to act like pigs, they are going to feel like pigs, whatever ‘pig-ness’ is. We don’t know. We are not pigs.”

Animal rights groups would also have worries over future organ farms. Scientists have selected pigs to carry our organs because they are common, well-understood and match us in size, but, as we’ve examined over Pig Week, they also share intelligence and a capacity for suffering. The organ farms of the future would likely subject the pig — an animal some people consider a beloved pet — to routine surgeries and intensive drugs. To harvest some organs, a pig would need to be sacrificed.

In weighing those risks, Scott says a crucial biomedical question to ask is “Why is this research important?” With Dr. Nakauchi’s research, the answer is pretty clear: 18 Americans die every day waiting for an organ transplant.

His pigs might make some uncomfortable, but they could offer a piece of porcine hope.