Up and down the East Coast, fishers, chefs and distillers are pioneering new uses for an overwhelming population of European green crabs.

The bad news about green crabs is that they’re pretty much everywhere. At least, that’s the case up and down much of the East Coast, from Nova Scotia to South Carolina. Flip over a rock and they’ll go running. There’s a certain sound they make darting through the mud and seaweed. It’s a wet clicking and squelching of claws that seems to spill from the rocks. It sticks with you.

Despite their abundance in the area, green crabs aren’t actually native to this part of North America. Their origin can be found in their full name: the European green crab. First introduced to these shores more than 150 years ago, they’ve made their mark.

Growing up in York, a small town on the coast of Maine just over the border with New Hampshire, Mike Masi spent many days looking for crabs. His mother worked nights at the local hospital and after shifts she would drop him and his siblings at the small beach nearby where friends could keep an eye on them.

Mike Masi holds a freshly molted green crab while his partner Sam Sewall and their team sort through others for bait.

“We were beach rats. Always clambering around the rocks and tide pools and stuff like that,” says Masi. “Now, I’ll tell you, at no point did I think that there was a future in that.”

But 30 years later, after a jaunt in California—where he studied marine science and worked on a great white shark diving boat—and a baker’s dozen of years spent working in education, Masi is back in the same waters looking for the same crabs he used to pull out of the knots of seaweed. Green crabs, that is.

The Threat of Invasive Green Crabs

Like all the best (or worst) invasive species, green crabs are voracious eaters, hard to kill, prolific parents and thrive in many environments. In ecology, the term ecosystem engineer refers to species that build and modify their habitat. Beavers engineer intricate dams, creating ponds that radiate life outwards. Green crabs are engineers placing explosives on load-bearing columns and beams, demolishing the ecosystems where they’ve been introduced, deftly disassembling the connections that hold everything together.

They eat seemingly anything, including each other. They devour mussels, oysters and soft-shell clams, which are sometimes called steamers. One of the most valuable commercially harvested marine species in the state of Maine, soft-shell clams have been decimated by hungry green claws. They also undermine salt marshes, causing the creeks and channels to collapse and the marsh to wash away.

But the bad news about green crabs—and their abundance—is good news for Masi. That’s because he’s fishing for them as a source of food.

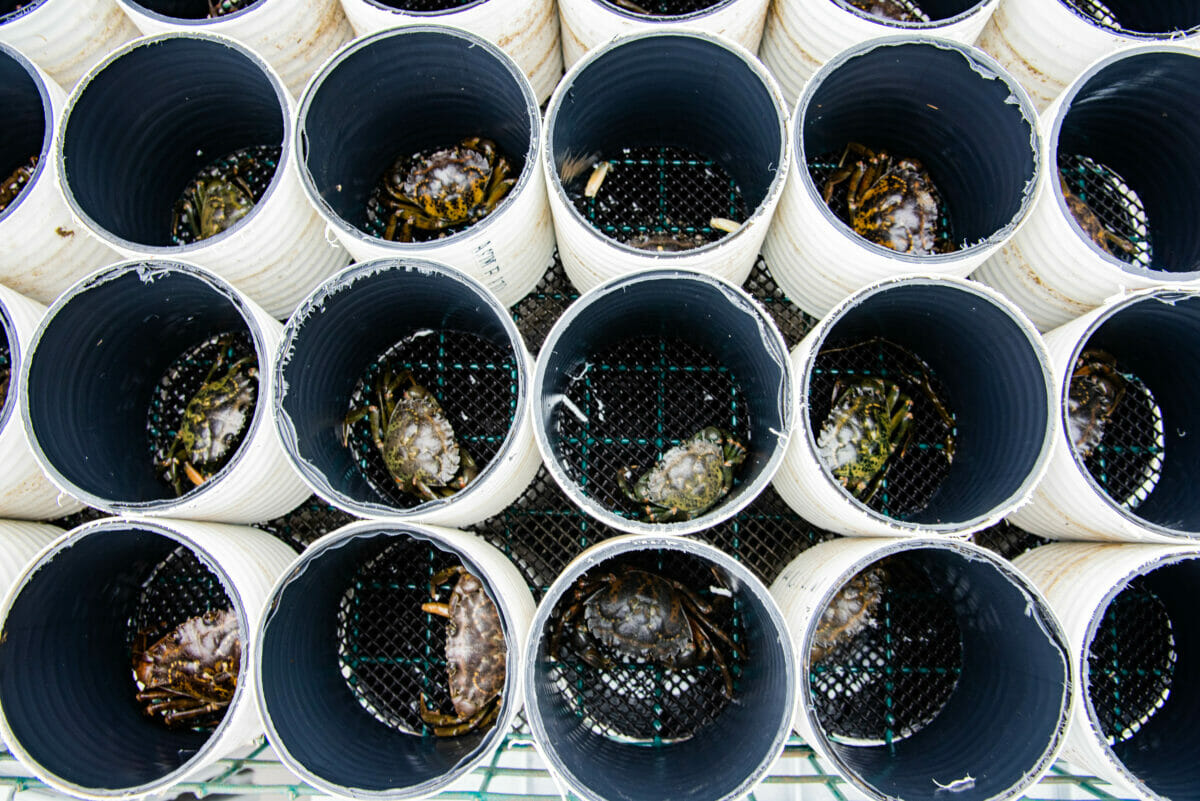

Sorting through green crabs is a numbers game. These crabs are being sorted and shipped for bait; none of them were ready to molt.

Masi first fished for green crabs with his marine science students at York High School, where he taught until 2021. He and his students applied for a grant from the York Sustainable Fisheries Fund, a local nonprofit, to monitor populations of green crab in the York River. The grant got them a few traps, Masi found a skiff to putter around the river and, suddenly, he and his students were catching pounds and pounds of green crab.

Fishing, however, is not the challenging part of harvesting green crabs. “If you’re using good bait,” Masi says, ”you can catch 30 to 40 pounds in a trap on a one- to two-night set.” The hard part is that green crabs are best eaten soft-shell, just after they’ve molted and shed their exoskeleton in order to grow into a new, larger shell. Unlike with lobster or a larger crab such as Dungeness, picking the meat out of a green crab isn’t very rewarding. They’re small crabs, with shells a few inches wide at most, and their spindly legs aren’t especially meaty. But in their soft-shell form, you can eat the whole crab—just like the prized soft-shell blue crab from the Mid-Atlantic.

RELATED: Finding New Uses for Crab Shells in Agriculture

In order to get a freshly molted crab, you catch as many crabs as you can and then figure out which are about to molt. Each crab goes into a unit in a “condo”—trays made from mesh to prevent fighting or cannibalism (remember, green crabs will eat each other if they’re hungry enough). The condo complexes (crates) stay in the water and you check them for molted crabs at every low tide. Molted crabs are obvious—suddenly one condo unit holds two crabs. One is empty, the old shell discarded like dirty laundry, and the other is the fresh molt, soft like wet leather and ready to be cooked.

Pre-molt green crabs are separated into condos so Masi can keep track of which have molted and to prevent cannibalism between crabs.

Identifying crabs that are about to molt is a muscle that must be trained. It’s closer to an art than a science, although Masi had help from a scientist to learn. Gabriela Bradt from New Hampshire Sea Grant and UNH Cooperative Extension has worked to build a green crab fishery for years. Masi was first inspired to give commercial fishing for green crab a shot after hearing Bradt speak at a local event.

Male green crabs molt in early summer in York, Maine. The male molt is more intense and concentrated than the female, making for better fishing. In the first week of June, Masi and his crew were working in overdrive: Fishing, sorting, checking; rinse, repeat. Checking every low tide sometimes means checking at midnight as the tides swirl around the clock, advancing an hour each day.

The rarity and inexact art of identifying pre-molts makes this fishery a numbers game. “This is not a small batch operation,” Masi explains. “This is ‘catch them by the million and find the three, four percent that are useful and do something with them.’” Each haul of the trap has been close to 90 percent female, and not every male is a pre-molt. Some are shiny and green, a crab with a new hard shell. The ones that got away.

Finding New Uses for Green Crabs

Playing a numbers game with such an abundance of green crabs tends to up your odds of success, and even hard-shell crabs can be useful. Buyers of the invasive green crabs have included whelk fishermen using the crabs as bait and a local Buddhist temple for Cambodian New Year, where they were pickled for a Cambodian dish called Salty Crab. One New Hampshire distillery, Tamworth Distilling, has used green crabs to flavor a whiskey (although the crabs weren’t Masi’s).

RELATED: The Joy of Cooking Invasive Species

Masi’s soft-shell green crabs are finding wider success in restaurants in York and nearby Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a picturesque riverside outpost for sea-foodies on the highway to Maine.

Ryan Boyd, culinary director of Row 34, has been buying them whenever possible from Masi. Row 34 is a restaurant with a focus on oysters, beer and seafood—most of it local—with locations in Portsmouth, Boston, Cambridge and Burlington. He first tasted green crabs through Masi’s business partner Sam Sewall, nephew of Row 34 owner Jeremy Sewall.

“Last year, [Sam] brought in six crabs in a homestyle-like little box and I’m like ‘What is this craziness?’” recalls Boyd. “We fried them up and I was like, ‘These are really good, dude. If you ever have more of these, give me a call.’”

Row 34’s soft-shell crab sliders with hoisin aioli and pickled daikon, a dish that turns heads in the dining room, according to culinary director Ryan Boyd.

This year, the menu features green crabs in the form of a soft-shell crab slider with hoisin aïoli and pickled daikon. Boyd stacks three fried crabs on a bun, breaded legs poking out where you usually see a patty. “Usually, one [order] goes to the restaurant, through the dining room, and then everyone kind of head-turns, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ And then all of a sudden you sell three, four more. It’s a bit of a showstopper,” Boyd says.

The unique thing about the green crab fishery, at least in New England, is the benefits beyond employment that it offers. By Masi’s rough math of 10 crabs per pound, they’ve removed about 35,000 green crabs from their small estuary and the York River. The ease of fishing so many crabs means they aren’t going to solve the green crab problem overnight—which is good if you’re trying to make a fishery out of it—but they have seen a decrease in their catch in the harbor where they do most of their fishing.

RELATED: How New England’s Jonah Crab Turned From Garbage To Delicacy

Masi sees an opportunity for localized preventive fishing for green crab, especially around soft-shell clam habitat. A town interested in keeping its clam beds alive could pay someone like Masi to set traps and fish them. Masi sees potential for a much bigger fishery in the future, and he isn’t shy about sharing his techniques.

“We’re going to put it out there for other harvesters to take it or leave it and see if they want to try to join in,” he says. “Because there’s certainly no shortage of [green crabs] and they’re selling at restaurants really quickly. So, we haven’t even come close to hitting demand.”

Everyone seems to be rooting for the green crab fishery to succeed—unusual for most commercial fisheries. “You’re harvesting, feeding people, employing people and doing ecological good. That’s extremely rare,” says Masi. “And so it feels great to be a part of that.”

Believe a greater effort should be made to market these crabs to Asians, specifically Chinese, Japanese and Koreans. They like any sort of seafood. Way back in Korea saw people sucking tiny cooked snails out of shells, ate them while watching movies. Might even be an export market..

Can eyestalk ablation be used to induce molting? Place crabs in individual “condos”, ablate the eyestalks, feed them well, and periodically check for molting.