Cannabis farmers in California were ready for big returns when legalization passed in the state. Now, they’re just hoping to break even.

The rhythm of North San Juan, CA has changed. Locals—all 151 of them, according to the last census—still grab coffees or a bite at The Ridge Cafe or Mama’s Pizzeria and pick up soil and starts at Sweetland Garden Mercantile. Everyone still knows everyone, and the tiny town still has its own version of hustle and bustle.

But the annual influx of seasonal cannabis farm workers is a thing of the past. Known locally as “trim-migrants,” crowds of energetic young folks would pass through each year to clip buds from the plants, once so prolific in the area’s single-crop gardens.

Another way to visualize the change to “the ridge”—as the area between the middle and south fork of the Yuba River is known—is via Google Maps or a real-estate site such as Trulia. Zoom in using the satellite view to find an array of garden beds and greenhouses tucked back in the woods; search available properties and note all those advertising that the place comes with a “complete garden infrastructure.”

This is the fallout of California’s Proposition 64. In November 2016, the state legalized the growth and regulated sale of marijuana. And while it seemed to present an opportunity for the silent backbone of this and many other local economies across California, the actual effects of the regulation presented a much different cautionary tale.

In the fall of 2022, Nevada County, which stretches from California’s central valley to the state border with Nevada, counted fewer than 20 canopy acres of cannabis growing across 112 assigned permits. Darlene Markey, owner of Sweetland Garden Mercantile, knew of 25 local growers who registered with the county and tried to make a living growing and selling legal cannabis; today, she can think of only four who are actively growing and selling product. Those who kept their business on the black markets haven’t fared any better, she says.

According to the dozen or so growers I spoke with for this story, the new regulations, not to mention the plummeting prices from the commercial grow operations, have effectively boxed them out. The government has implemented a host of tests for THC potency and pesticides that growers find both arduous and often capricious. Even the building codes seemed targeted at keeping black market growers from making the transition to legality; all buildings on a grow property have to be fully permitted. While this is a standard requirement for any legal business, growers had been keeping their operation under the radar; to comply with the new regulations meant a sudden investment of big dollars.

“I was excited at the beginning,” says Markey. “I thought a lot of these guys can finally have legal jobs. But it just backfired on everybody.”

Sweetland Garden Mercantile. Photography by Caleb Garling.

Ridge life

Growing pot on the ridge, an area I’ve called home since 2020, dates back to at least the 1960s, when those homesteaders looking to escape city life took an interest in the psychoactive plant. Cultivating fruits and veggies in the Sierra Foothills comes with numerous environmental challenges—late frosts, blights, armies of deer and gophers—but the copious summer sun and font of springs and creeks meant the weed, so to speak, was a relatively easy crop.

But in the early 1990s, the area started to see gardens move into heavier production levels. Growers didn’t yet have the legal cover of medicinal use and had to work beneath the canopy in complete secrecy. But the payoff was high. A pound of dried marijuana, which can be harvested from a plant or two, could sell for upwards of $6,000—big dollars anywhere, but especially for a rural area dependent on the ups and downs of mining, logging and ranching.

Pat, who spent 15 years as a grower on the ridge, and like the other former growers in this story elected to use a pseudonym in order to protect his employment opportunities, calls the early ’90s on the ridge a “very risky outlaw time” when “people had to grow a lot of plants for modest yield.”

Then, in 1996, California legalized medicinal-use marijuana. Finding a doctor who could write a “prescription” to legitimize a grow was trivial, and by the early 2000s, word was out that there was money to be made in them hills. The area soon flooded with operations cultivating their allocated six plants.

“The county had a different feeling then,” says Pat. “We would take our trim crews out for end-of-year celebrations and fill up restaurants. It was loose and free and even though the old guard curmudgeons would rail about pot publicly—it did attract some bad energy—they knew it was a golden goose.”

The money flowed not just for the local economy but for the seasonal workers. Trim-migrants skilled with a pair of scissors—there is a technique to cutting away the buds properly—could make up to $1,000 in a day. Yet the vibe was much less migrant working and far more party or Burning Man. The average trim-migrant tended to be young, free-wheeling, twenty- and thirty-somethings, from the US, Europe, Israel and affluent parts of Central and South America, using the earnings as a launching pad for more adventures abroad.

“I could make in two weeks what I’d spend in a year,” a former trim-migrant using the name “Conway” told me.

Conway eventually used the earnings to start his own grow operation. He and his crews would spend blistering summer afternoons agonizing over soil quality, staking the plants, catching pests, fixing irrigation systems and all the other ins and out of maximizing the plants’ yields—and then blow off steam at night, post up along the banks of the Yuba River for a swim or to plan their next trip.

“I saw so many people attached to the lifestyle of growing,” says Conway, “despite the market.”

Preparing for harvest season at Hill Craft Farms. Photography courtesy of @hill_craft_farmsnc

Not that easy

The picture presents as a kind of libertarian, Wild West fun—and to many it was—but there were consequences. Most growers had stories of break-ins, robberies and plants being ripped off; there is the infamous tale of a kidnapping and deadly car chase down Highway 49. I had heard rumors of Mafia henchmen and cartels, and while such characters probably did get involved downstream, no one I spoke with could corroborate the idea they were running around causing problems on the ridge.

“It was all decentralized and under the radar,” says Pat. “So, the big gangs and the mob didn’t have any central pressure point where they could extort money or lean on people.”

Law enforcement had a similar problem, but it was more active in tackling it. Even though grow operations were legal in the eyes of the state, federal law enforcement—whose laws supersede the state, according to the US Constitution—would spread through the hills (often with a supportive nod from the county) and arrest growers for their possession and intent to distribute a Schedule 1 substance.

“People we knew went down every year,” says Pat. “Either in raids or in selling and transporting. The county and the feds were aggressive and relentless. It was a target-rich environment. I spent a while on my knees in the driveway with an AR15 to my head. [Law enforcement] loved doing that kind of stuff.”

Photography courtesy of @hill_craft_farmsnc

Seed the light

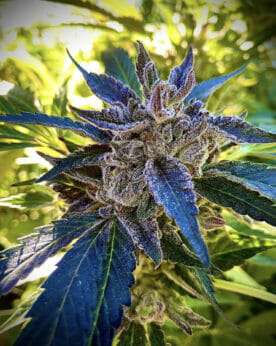

The bottom dropping out on cannabis growing wasn’t entirely due to legalization; the way cannabis was grown also went through a seismic shift. Light deprivation—or “light dep”—is the practice of planting in the winter months, as opposed to May and June, and allowing the plant to grow only for a short window of time, perhaps eight weeks. Growers then simulate shorter days—in other words, they simulate fall—by shielding the plant from the sun and induce the plant to flower early. (The cannabis flower is what’s harvested and smoked.)

This drastically changed the economics of selling. Typically, the market flooded with supply during the fall harvest. As such, prices tended to be at their lowest. But if a grower was “smart or able,” as a former grower using the name “Paul” put it to me, they held onto their product until the winter or spring, and sold when prices had come back up due to the dwindling supply. Conway, for instance, would bury his harvest in the woods for months until he was ready to sell.

But because light dep didn’t need the full summer to grow, cannabis began flooding the market in the off-months. With less scarcity, the bounceback in price weakened and the price curve flattened. In addition, says Paul, connoisseurs of marijuana, especially those in the club scenes, started to prefer light-dep weed over that grown in natural cycles.

“Yeah,” Conway grumbles when I ask how the technique changed business, “light dep fucked things up.” Essentially, he says, “People became addicted to freshness.”

What’s next

Many of the growers I spoke with have taken the change like any other in life; they’ve returned to their previous vocations as yoga instructors, builders, timber fellers and herbalists. Pat returned to his work as a music technician, Paul as a lawyer; Conway now sells solar energy systems.

Here and there, I did encounter some resentment among former growers towards the lack of public outcry for their cause. Despite the fact so many Californians and Americans abide or consume marijuana, there’s a comeuppance vibe many of them encounter when describing their story. “We were treated like criminals,” a grower told me.

There’s also overwhelming frustration with the county and state. According to growers, county planners and legislators made appearances of taking their transition to legality into consideration, but, in the end, they released regulations that catered to commercial farms with big investment capital.

The Cooper Brothers. Photography courtesy of @hill_craft_farmsnc

Daniel Cooper and his twin brother David have made the jump from black market growers to running the above-board Hill Craft Farms today. “The state regulations pulled the carpet from beneath us,” he says.

One of the deepest frustrations I’ve heard is that growers must sell to dispensaries, rather than be able to sell directly from their farms. Reminiscent of the “three-tier system” of alcohol distribution, where breweries and distilleries must sell to a third party distributor to reach stores and restaurants, the state argues the rule is to keep a close eye on a psychoactive substance. Still, it is a tough pill to swallow when California roads brim with stands selling fruits and veggies, not to mention the legions of microbreweries across towns and cities.

Sweetland’s Markey hopes some day the ridge can be a place where connoisseurs come to taste and sample. “They do it in wine country,” she says with a wave towards Napa and Sonoma County. “Why can’t they do it with herb?”

When we spoke in January, the Cooper brothers said they were getting close to finding their groove in this new world of legal growing, even if, like many farmers, the profits are razor thin. But they came to the ridge 16 years ago to do this and they have no plans of giving up now.

“It’s not just growing,” says Daniel. “It’s a whole culture. We’re holding it down because it’s what we love.”

The rich get richer and the poor get poorer so goes the weed market

Personally as one who graduated in the late 70’s in Anderson, and spent all of his youth and adulthood camping and backpacking in the Trinitys and Yolla Bolla wilderness area, I was overjoyed to see the legalized growers. Made the woods safer. Now if the Feds will get off the pot and legalize it, maybe the cartels will get the hell out of my hood with their slave labor. Then we can get back to safe use of our forest.

Light dep?? My assumption is that most people were growing indoors where you can easily have three harvests of full sized plants every year. Using SoG you could do 7 or 8.

These guys are trying to win a race with a horse and buggy. It’s not wine, and if it were, the majority of consumers would be just fine with MD 20/20…

Legalize It! And I mean unregulated. You can grow tomatoes and sell by the side of the road that is what legal pot should be.

From what I have seen, in CA the cities, counties and the state tax the heck out of sales in the cannabis stores. Noticed in my town, there are three cannabis stores, two within sight of each other and the third not much further away. They seem to be doing well.

Observation – some decry cannabis as a dangerous drug. Am sure it is not for everyone. But alcohol is far worse, kills many thousands, directly and indirectly, causes a great many problems for families/society. Tobacco is just as bad, kills hundreds of thousands yearly.

I voted for Prop 64 so that I could legally grow my own and NOT buy it from a dispensary or on the black market. It was pretty obvious that certain politicians (Lagomarsino) had a vested interest in cannabis when he renegged on the 5 acre cap because he had investment in corporate grow ops. They said they were going to “protect the mom and pops” just to get the prop to pass, then as soon as it did they removed the 5 acre cap. Now its a classic boom and bust cycle that only the hardiest old school growers… Read more »

Hang in there! Change comes slowly. Remember, we’re in this together – you all as your business, consumers supporting your businesses.

The illegal growers are upset that in order to be legal, they have to do meet code that all businesses have to follow? They can’t just keep selling their product unregulated? I wouldn’t want to buy vegetables that didn’t have safety regulations such as types of pesticides. Why wouldn’t I want regulations on growers?

Call 1 800 WAAA. Dopers

So how could I get a job at a weed farm I enjoy doing it so I might as well try to find a job doing it and I will relocate for the job