How Louis Bromfield, a Pulitzer-winning author, became an unlikely celebrity farmer.

When Louis Bromfield first arrived on his farm in Richland County, Ohio, he was shocked at the state of the soil. Generations of unsustainable forestry and grazing practices had left the topsoil all but useless. Rain and lack of ground cover had caused the earth to wash away, leaving massive gullies scarring the landscape. Little wonder that the farmers he purchased from had been so keen to sell. The land was barren.

That Bromfield was even on the farm in the first place was an unexpected chapter in a fascinating life. There was a time when Bromfield was mentioned in the same breath as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway. In 1927, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his third novel, Early Autumn, about a woman keen to escape her Puritanical New England background. He also moved in Hollywood circles as a screenwriter. Born in Mansfield, OH in 1896, he studied agriculture at Cornell, before serving as a U.S. Army Ambulance Corps volunteer with the French infantry during World War I, and then moving to New York, where his career as a novelist took off. In 1925, he moved to France, joining the thriving expat literary community. For the next 13 years, he lived in France, while taking extended trips to India to learn more about local horticultural methods and to carry out research for several novels. Along the way—and several decades before Rachel Carson and her contemporaries birthed an environmental movement—Bromfield would aim to revitalize American agriculture in a way that was both profitable and sustainable.

His time in both France and India would influence his relationship with agriculture greatly. In France, he was struck by the importance of and devotion to preserving “terroir.” In India, he observed the large-scale use of composting to fertilize the soil. Meanwhile, in America, so much pre-industrial knowledge had been lost in the quest for industrial advancement. In chatting with other farmers and agricultural innovators, he saw how tools such as the moldboard plow intended to increase productivity but did so at the expense of the soil itself. He was convinced that successful farming entailed working with nature instead of fighting it.

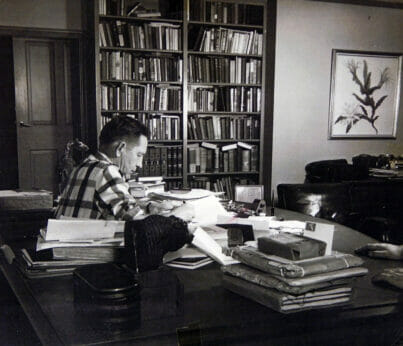

Louis Bromfield, courtesy of Malabar Farm.

In 1938, Bromfield, his wife and three daughters returned to Ohio. He had purchased several large tracts of farmland and harbored an idyllic dream of raising his children on a traditional American farm. He knew from his time in Europe that war was, once again, looming on the horizon. Bromfield felt it was vital to be self-sufficient and wanted the farm, which he named Malabar, to offer safety, food and shelter to his family and farm employees. However, what he saw was far from idyllic. That barren landscape, so devoid of life, was almost worthless.

Anneliese Abbot, author of Malabar Farm: Louis Bromfield, Friends of the Land, and the Rise of Sustainable Agriculture, notes that the US Department of Agriculture took the view that soil “is the one resource that cannot be used up.” The Dust Bowl was proving otherwise.

Bromfield set to work learning as much as he could about soil conservation. He was an early adopter of a new type of plow, created by Kentucky farmer Edward Faulkner. Faulkner was mocked for his claims that the widely used moldboard plow was damaging the soil by not allowing organic matter to decompose properly. Bromfield thought there might be something to his ideas, so he tried Faulkner’s redesigned plow, with excellent results. He became a vocal proponent of so-called “trash farming”—commonly known today as “no-till farming.” The method allows organic matter to decompose in the top layers of the soil, thereby replenishing nutrients and reducing the need for additional fertilizers. Bromfield remained ever mindful of the connection between soil health and human health. In his 1946 collection of essays, A Few Brass Tacks, he wrote, “As soils are depleted, human health, vitality, and intelligence go with them.”

Bromfield turned Malabar around, transforming it into a model of modern sustainable agriculture. In 1940, he wrote Pleasant Valley, detailing the steps he had taken to replenish the soil and the results of his work. On weekends, hundreds of people would flock to the Ohio farm to see Bromfield demonstrate the methods he endorsed. One such weekend in 1952, sponsored by Successful Farming magazine, saw thousands of visitors, with some reports listing as many as 10,000 people on the farm. Bromfield’s daughter Ellen later recalled it as an event she had no desire to repeat.

Louis Bromfield with farm visitors. Courtesy of Malabar Farm.

Louis Bromfield was recognized as an agricultural pioneer, but he did not work alone. He learned from fellow conservationists and organizations such as Friends of the Land. By turning Malabar into a showpiece for these “new” methods, Bromfield helped convince the nation that it was possible to feed both the soil and the people. At the same time, he remained a businessman, preaching that a farm could be both sustainable and profitable, as long as farmers learned to “work with Nature rather than fighting her.” Conservation, he argued, was good business.

In the mid-1950s, Bromfield began to draw up plans to create an ecological foundation at Malabar. Unfortunately, before that could become a reality, he passed away in 1956. Nevertheless, the Malabar Farm Foundation continues his educational work and Malabar is a national monument. Thomas Bachelder, a naturalist and president of the Malabar Farm Foundation, says that Bromfield’s greatest contribution to the sustainable agriculture movement and environmental stewardship was education. “Most of the innovative practices that he employed at Malabar Farm were already known and being applied elsewhere,” Bachelder says. “However, Bromfield was able to use his fame and gift for writing and speaking to get the message out much more effectively and to a much wider audience.”

Farmer and environmentalist Wendell Berry believes that good farming “is never the work of one individual, but the work of those living and dead.” With that in mind, Louis Bromfield is certainly part of an ongoing agricultural heritage that can only help to, in Berry’s words, “restore the richness of the country.”

I first read Pleasant Valley in the ’70s, I still have the book in a place of honor on my bookshelf. Our family has used Bromfield’s principles in our home garden for decades.

Excellent guidance.

He is our unsung hero!