When Paul Polak started asking poor, rural farmers in developing countries what they would need to pull themselves out of poverty, he did something unusual. He talked to them like customers, not like objects of charity.

The time was 1981, and Polak was starting his nonprofit International Development Enterprises (IDE), which would go on to help 20 million of these farmers by designing affordable irrigation tools and mass-marketing them through the private sector.

Today Polak has stepped down from his day-to-day role at IDE to work on four for-profit multinational corporations, all aimed at transforming the livelihoods of 100 million customers who earn about $2 a day, mainly rural farmers. The corporations will cover innovations for safe drinking water, affordable education, solar-powered irrigation, and transforming agricultural waste into low-carbon emissions. Each company aims to generate $10 billion in annual revenues — and earn sufficient profits so that they can attract investors.

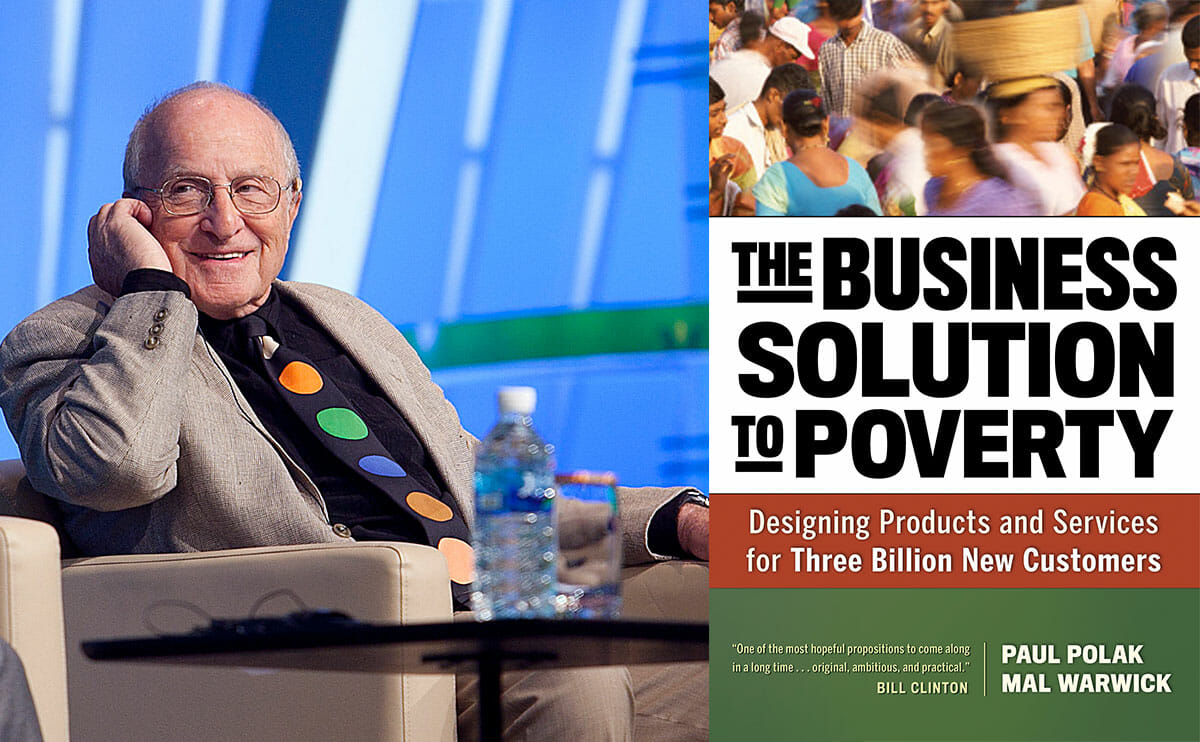

Treating the poor as consumers and empowering them to “vote with their feet,” as Polak likes to say, is one part of his “Business Solution to Poverty” plan. The other part is demonstrating to companies the market potential that small farmers and the rural poor hold, and helping those companies develop products that the poor both need and can afford. These ideas are the focus of his new book, written with Mal Warwick, on the subject, The Business Solution to Poverty: Designing Products and Services for Three Billion New Customers.

We spoke to Polak on why business is best when it comes to helping people, particularly farmers, out of poverty and about the latest project he’s working on: solar powered irrigation.

Modern Farmer: What’s wrong with charity, and why is business a better solution for helping the poor?

A typical thing is that a government or charity organization will pay for all the hand pump equipment and most of the building of the well. But when the hand pump is installed the questions is, who owns it? All hand pumps break eventually, and when it comes time to fix it, no one fixes it, because no one own it.

Paul Polak: I don’t believe there’s anything wrong with charity or government support for things. But as far as the big picture, in my view, the conventional approaches of development to ending extreme poverty have pretty much failed. And they’ve failed for a variety of reasons. First of all: you can’t donate people out of poverty. Poor people have to invest their own time and money to move out of poverty. But you can provide some of the essential tools they need to move out of poverty. After 30 years of experience, I’ve seen that treating people as customers — instead of recipients of charity — to be most effective way to do that.

I didn’t start with any ax to grind one way or another. I simply started by interviewing poor people themselves in depth and learning about their lives and what they need, and how they felt they defined their poverty. One of the limitations of the charity model is often the organization that provides the tools or contributions to poor people often miss the mark.

An example is in Eastern India. A very common global strategy for providing safe drinking water to villages and households that don’t have it is to install hand pumps. A typical thing is that a government or charity organization will pay for all the hand pump equipment and most of the building of the well. But when the hand pump is installed the questions is, who owns it? All hand pumps break eventually, and when it comes time to fix it, no one fixes it, because no one owns it. It’s seen as a UNICEF pump or a government pump. If you do a survey two years later between 50 percent and 75 percent of those hand pumps aren’t working.

MF:How were the projects IDE did handled differently?

PP: With IDE when we sold irrigation pumps to farmers and they used them to gain income, 93 percent of them were working when we checked back two years later.

When you treat people as customers they vote with their feet. They either buy it or don’t buy it and it not only puts the poor person in a position of respect, but it makes the donor or the agency or the company have to come up with something that the customer will vote with their feet to buy.

MF: What advice do you have to a individual or company that has a product idea for these $2-dollar-a-day farmers?

When you treat people as customers they vote with their feet. They either buy it or don’t buy it and it not only puts the poor person in a position of respect, but it makes the donor or the agency or the company have to come up with something that the customer will vote with their feet to buy.

PP: There are three key steps. One, go to where the action is. You can’t design an effective product or strategy from your office. Two, talk to the people who have the problem and actually listen to what they have to say. And three, learn everything there is about the specific context of the problem.

MF: Can you discuss one of your new companies, Sun Water? It’s a photovoltaic irrigation pumping project.

PP: Solar pumping is very important in the agricultural sector. In India for example, there’s a lot of shallow ground water used for irrigation, and there are about 20 million diesel pumps operating in India now. The advantages of a diesel pump are that it is relatively inexpensive. It costs maybe $300 to $500 dollars. The disadvantage is you probably will spend $400 during the season just for diesel. That’s not even taking in to consideration the environmental impact of the carbon emissions of burning diesel.

Photovoltaic solar offers the perfect alternative. It’s virtually zero carbon emissions. The key problem though in using photovoltaic is that even though the price of solar panels has been coming down, they are still way too expensive to be competitive with diesel. The basic mission in the affordable pumping solar project is to cut the cost of photovoltaic pumping by 80 percent and then to market it successfully and profitably to farmers, starting in India and going global.

Polak explains the project in this video:

MF: How many people will a project like this help?

There are over 500 million farms in the world. Eighty-five percent of all the farms in the world are less than 5 acres. In the big picture when people talk about agriculture they pretty much assume it’s big farm agriculture and the Western model. Most of the farmers in the world are hidden from view.

What we need is whole generation of agricultural research that is meaningful to the 85 percent of the farms in the world that are less than five acres.

This interview has been edited and condensed.