Cities may not compost your dog poop yet, but you can start now.

Around 6.5 million tons of [mostly] plastic-wrapped dog poop winds up in landfills in the United States every year. As most cities see it, that’s the only safe option.

Unlike wildlife scat, which spreads seeds and returns nature’s nutrients in a balanced way, most conventional pet diets yield large amounts of waste.

The average dog produces about three quarters of a pound of poop per day, or 275 pounds per year, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Philadelphia accounts for tens of millions of pounds of dog waste annually, while New York City contributes 82,125 tons.

A pile left to rot on the ground can take months to decay, potentially shedding bacteria, viruses and worms. The nutrient-rich waste is likely to get into storm drains and waterways, helping fuel toxic algal blooms.

So, scooping seems like an easy win. But what about that plastic bag that’s typically part of the bargain? In the small city of Morro Bay, California, about 1,000 bags are used for each dog’s waste per year. These, too, get left on the ground, where rain can wash the entire neatly tied package into waterways.

A trash can overflowing with dog poop bags in San Francisco, CA Image from Shutterstock

A study estimates that up to 1.23 million tons of dog poop bags are disposed of annually around the world. It’s a small fraction (0.6 percent) of all plastic waste, but as the authors note in their title, their brief life cycle makes them “a non-negligible source of plastic pollution.”

Some cities even require pet waste to be double-bagged to shield workers from the contents.

In landfills, whether it’s incinerated or sits slowly decaying, poop adds to methane gas emissions. Packaged poop can take hundreds of years to break down, even in bags deemed compostable or biodegradable; certifications that are based on commercial composting conditions, not landfills—but US industrial composting facilities don’t accept pet waste.

The Biodegradable Products Institute, which sets standards for such bags, stopped certifying pet bags for the US market for that reason.

“I would just like to find one commercial composter in the US that accepts dog waste, period,” says Gary Bilbro, sales director at EcoSafe Zero Waste bags, on a web post. Faced with a dog waste composting desert, EcoSafe quit selling its certified compostable doggy bags in the US. “Our Canadian markets purchase hundreds of thousands monthly, but most of the Canadian composters accept pet waste.”

In fact, dozens of communities in Canada, in the provinces of Alberta, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan, compost dog poop, saying it reduces the amount of plastic going to landfills, while studies have found it can cut the volume of dog waste in half.

In the US, dog parks are catching on.

Lessons From Mushers and Others

Composting is the controlled breakdown of organic matter into humus, a rich soil amendment many prefer over chemical fertilizers. Farmers and gardeners often use livestock manure from poultry, cattle or horses. But when it comes to dog manure, the process is frequently shunned over fears of pathogens—despite the widespread practice of fertilizing crops with “biosolid compost”—sewage sludge—which has been found to contain toxic PFAS chemicals and many other hazards.

Mingchu Zhang, professor of soil science and agronomy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, cautions in an email about infectious organisms in dog poop that might survive composting. “That is perhaps why most cities prohibit it.”

Yet a number of studies and pilot projects have helped pioneer the composting of dog waste— and unlike biosolids, it’s not being spread on food crops.

The first scientific study took place in Fairbanks, Alaska in 1991. In the land of the Iditarod Trail Dog Sled Race are scads of dog lots near wetlands. As snow melted, piles of manure reappeared and infiltrated waterways. Armed with an EPA grant, conservation agencies and dog mushers worked together to find a fix.

In summer, poop is mixed with sawdust in covered bins in a ratio of about 30 parts carbon to one part nitrogen. Every one to two weeks, rangers give it a stir, and in one to two months, it shrinks into a smaller pile of crumbly soil. Over winter, there’s no stirring the frozen mix; poop is collected, but the entire process takes one to two years.

Composting is still in use at some sled dog kennels, including one in Denali National Park, the only national park that composts this waste from its sled dogs as part of its commitment to starve the landfills.

“Since it’s from dog manure, it is not recommended for vegetables, but there are a lot of other uses for it,” says ranger Mitch Flanigan. In 2021, the kennels produced 6,650 pounds of compost. A lot of it winds up in flower pots in the kennel and visitor center. Some is donated to locals through signs he posts in stores, he says. One resident used the material as backfill for a septic system.

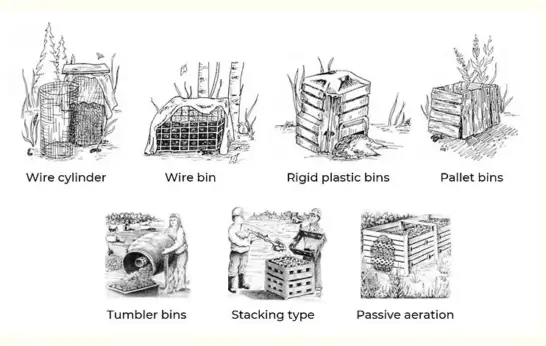

Different styles of compost bins used by Denali State Park

Composting is also thriving at many US dog parks and other places that took a chance on the maligned material. New York City’s Battery Park uses it, once fully cured and tested, for plantings in highway medians.

Mississauga, Ontario, which in 2019 began processing dog poop at waste-to-energy facilities, turns some into fertilizer. City spokesperson Irene McCutcheon says that, in 2023, almost 14 metric tons of dog waste was collected and diverted—”the equivalent of powering close to eight homes for a year.”

Repurposing dog poop is also helping Colorado front range communities inch closer to their zero waste goals. Rose Seemann, who started a composting company called EnviroWagg, has helped forge a path by working with Metro Denver and Boulder dog parks, hiking trail heads and businesses.

The poop is collected by a pet waste removal service partner, which delivers it to the composting facility. The finished product is used only on landscaping at the compost site, with no distribution to the public, says Seeman. Past batches intended for sale have tested safe. Each batch needs to be tested separately, but once a batch passes EPA standards for pathogen levels, it can be used for edible plants.

So, why do we recycle sewage sludge in the US but not dog poop?

Plastic Ick

Ten years ago, EnviroWagg created and test marketed a product for use on herbs, fruits and vegetables. It tested well for plant nutrients and passed EPA standards for pathogens, making it “an excellent soil amendment for both landscaping and edible crops,” says Seemann.

But that wasn’t enough.

“The ick factor made it a difficult sell.”

Envirowag’s composting site in Longmont Colorado. Photo courtesy of Rose Seemann

Today, the company doesn’t turn a profit, she says, and that’s not unusual. “No one has figured out a way to monetize the process.” Programs such as those in NYC are carried out by parks departments, while communities in Canada and Australia accept pet poop with food scraps and yard waste in residential green bins.

The EPA doesn’t recognize it as a waste stream, she says, “although audits and guesses say it adds up to around 12 percent of residential waste.”

But any commercial composting facility that follows processing regulations and testing protocols can do it, says Seemann. And professionally finished compost can be used for any planting, even produce.

“It’s just a perception issue.”

The main challenges in getting dog parks and cities to take it on are convincing the public decision-makers who authorize budgeting, and finding a regional composter willing to accept pet waste, she says.

And once again, plastic trips things up.

Dog park composting pilot projects live on—or not depending on people knowing what goes where. Two dog parks in Calgary recently ended a six-month trial because people were tossing plastic in the composting bin. Only certified compostable bags were allowed.

Adding dog poop to US organics curbside collection programs would create a mess for sorters who have to remove contaminants such as plastic, and in turn, the compost facility charged with managing it.

According to the Biodegradable Products Institute, many doggy bags advertised as compostable are actually petroleum-based products treated with chemicals to hasten their breakdown.

To get around the plastic problem, Friends of Hillside Dog Park in New York City placed scoopers and biodegradable brown paper next to the compost bins.

Do-It-Yourself

Poop near a storm drain is one thing, but the Environmental Protection Agency sees the benefits in repurposing it. “Dog waste composting is a natural process that requires air, water, organic matter, microbes and a little human intervention,” its website notes.

Seemann says the big difference between commercial and DIY compost is that the latter should not be used on edible gardens unless it’s been tested. Backyard composters can struggle to maintain the high temperatures needed to kill pathogens. Denali rangers recommend home poop composters sustain a temperature range between 130°F and 170°F.

But the process—cooking, turning, curing a dedicated poop pile—isn’t that hard to learn. It can even be done in small spaces.

“Compost dog waste the same as other materials. The dog poo is green, so you need to balance it with carbon.” Rose Seemann

Add the variables of climate, weather and available materials to get a sense of the trial and error aspect. When any unfinished compost smells, it needs carbon—such as wood chips or shredded straw—and turning.

Zhang, the soil scientist at the University of Alaska, cautions about selling or giving away backyard compost unless it reaches US EPA standards. “People who use it on their own are responsible for themself for the issues that may arise from compost dog manure.”

Good composting, on the other hand, can keep problems in check while it shrinks the waste—and that mountain of plastic used to package it.

First paragraph mentions 6.5 tons of plastic wrapped dog poop ending up in landfills per year but that seems inconsistent with the rest of the article. Is a word missing? I don’t believe the author meant 6.5 million tons but 6.5 tons definitely seems too low. Other than that, definitely an interesting problem! Thank you for this interesting article.

But, what about the concept of bringing the poop home with you and flushing said poop down the toilet. Obviously, not the plastic baggie.

Alas, being an authority on dog poop, due to all the dogs that have chosen me as a life partner over my many years, I know way to much about what they eat on the beach or the ranch. And the need for internal and external parasite control, and whatever other things they ingest. [Mine are extremely healthy and rarely if ever need pesticides, antibiotics, thyroid medications, pain killers etc.] But most dogs do, so any compost that includes dog poop is about as far opposite on the spectrum as you can get from organic.

I’ve learnt a lot from the lessons and stories you’ve shared. Life is a journey.