Although many farmers and ranchers see beavers as vermin, ecologists are hoping to change their reputation.

It’s late October and Jon Griggs, manager of Maggie Creek Ranch in Elko, Nevada, still has more than a thousand Angus-cross calves left to wean. It’s been a decent year at the 200,000-acre spread, with enough forage for the 2,000 mother cows and their calves. Water, however, has been a concern—a perpetual one—with summer temperatures nudging towards the three digits amid a drought that has gripped the region for most of this century.

During the year, the cattle are moved to new grazing. In some pastures, Griggs must rely upon wells, some as deep as 800 feet, to water the livestock. Other pastures on the 200,000-acre ranch—an area larger than New York City’s five boroughs—are traversed by the Susie and Maggie creeks that, thankfully, provide a year-round source of water. This wasn’t always the case. For years, the creeks petered out into dusty gravel beds every summer. Then, beavers were reintroduced, and everything changed.

Photography by Shutterstock.

Thirty years ago, while still a young cowboy, Griggs, like most ranchers, regarded beavers as vermin that gnawed down trees and blocked irrigation ditches. The snaggle-toothed aquatic rodent was shot, trapped and its dams dynamited. By the 1990s, beavers were virtually gone from the ranch, due in part to cattle degrading the riparian (banks and wetlands) areas as they sought water and greener grass. Without beavers, ponds and creeks dried up. This happened not only on the Maggie Creek Ranch but the public lands where Griggs’s cattle grazed. Working with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which oversees public lands, riparian restoration began.

Griggs collaborated with BLM biologist Carol Evans. First, cattle’s access to creek beds during the spring and summer growing periods was restricted, allowing brush and grasses to regrow. As a result, creeks began widening, cooling and deepening. Willows took root, creating an ecosystem that could support beavers, which consume such woody species. Initially, Griggs wasn’t enthused about reintroducing the industrious creatures. Let the beavers do their thing, Evans assured him.

Griggs watched as a new generation of Castor canadensis began to re-engineer the landscape by building dams, creating pools of water that preserved the snow melt and the dozen or so inches of annual rainfall. The moisture created green oases half a mile wide that emanated from the creeks. Grazing expanded. Cattle had more and better-quality drinking water. Trout flourished. The creeks flowed year round. Today, Griggs says proudly, Susie and Maggie creeks are home to about 150 pairs of beavers, with one “major complex” of about 15 families. Now, he’s changed his tune, speaking at conferences across the United States and Canada about climate change and the benefits of introducing beavers to agricultural lands.

Beaver-engineered lands also provide a bulwark against drought-sparked wildfires that have consumed vast tracts—about one million acres in two conflagrations—in Nevada, says Griggs. Evans, who has since retired from the BLM, adds that healthy streams with beavers “work like a firebreak. And even if it’s burned, it comes back really fast.”

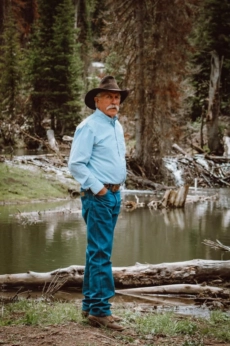

Jon Griggs at Maggie Creek Ranch. Photography courtesy subject.

Busy beavers

Several hundred years ago, North America was a lush Eden of interlocking streams, creeks, ponds, lakes and rivers, maintained by an estimated 200 million beavers. An influx of European traders meant that beaver became currency for Indigenous peoples, who swapped animal pelts—used to make gentlemen’s top hats—for guns, axes, needles, knives, beads and blankets. Like the buffalo and passenger pigeons, beavers disappeared from much of North America.

Landscape hydrology—how water moves over land— shifted: Wetlands were drained for agriculture and human habitation, and meandering rivers straightened. This, says Wisconsin’s Bob Boucher, president of Superior Bio-Conservancy (SBC), has been a recipe for environmental disaster. A straight stream with high banks concentrates the power and speed of water, acting like an enormous high-pressure fire hose. Flood waters gain momentum, overflowing banks and causing destruction and massive erosion, washing away critical topsoil, not to mention farms, homes and other infrastructure.

Beavers prevent such land tsunamis, creating wetlands that are similar to rice paddies, says Boucher, whose organization restores the hydrology of the Great Lakes and Laurentian Forest regions. During snowmelt or rainfall, the wetlands act as a giant sponge, storing the storm water, and hold “almost eight times as much water on the landscape.” Studies done by Boucher show that beaver dams lowered peak water levels from an intense rain storm by 40 percent. In one case, 500 Milwaukee suburban homes were taken out of a floodplain thanks to beavers, says Boucher.

Not only do beaver wetlands capture stormwater, they also function as a “sewage treatment plant.” Many farms and feedlots have runoff, whether this is excess manure, pesticides and herbicides or fertilizers such as phosphorus and nitrogen, both implicated in climate change. Beaver ponds lessen the concentration of such pollutants, says Boucher.

If floods and fires are to be tackled, agriculturists need to adjust negative attitudes towards beavers, says Boucher. “For a rancher or farmer out west, he’s thinking, ‘oh, they’re cutting my trees down.’ If he recognizes that they’re going to keep a lot more water on his landscape, he’s going to have better water quality, he’s going to have more forage. It’s thinking of them as an asset or a blessing as opposed to a nuisance, pest or vermin. That’s the shift of coexistence that’s necessary.”

Bob Boucher with a beaver. Photography courtesy of subject.

Living side by side

Jay Wilde is the owner of Diamondback W Ranch in Preston, Idaho, a 10,000-acre spread that includes national forest that has been in his family since 1933. Back then, Birch Creek, the main source of water for his 200 head of cattle, flowed year-round through the property. Decades later, as summers became hotter, the creek dried up by July, then early June. Without water, the cows couldn’t graze many of the pastures. Wilde was forced to pipe water in. A smarter idea, mused Wilde, might be to bring back beavers, which had once flourished but had since vanished, due to being “either trapped or shot.” He tried releasing beavers into the creek area, but they disappeared: “Maybe predators got ‘em; I don’t know.” Wilde connected with Utah State University Professor Joseph Wheaton, an expert in river restoration, who suggested constructing beaver dam analogs, or BDAs, a manmade beaver dam. This created ponds deep enough for beavers in which to hide. Six more beavers were released, which went on to build their own dams and lodges. Beaver habitat was nurtured. Cattle weren’t allowed near the riparian areas until the beginning of September, after wetland plants had gone to seed. This allowed new willows and rushes to grow for beaver food. “It’s management of the cattle. You got to get that right before the beaver deal is going to work,” says Wilde.

Work it did. Birch Creek, which is about five miles long, now burbles year round, thanks to about 250 beaver dams and “my guess would be 20 to 30 animals,” says Wilde. Even though there is now richer grass and plentiful water, Wilde has shifted his thinking: The bovines are permanently restricted from entering riparian areas, which now host wilderness creatures.

As a keystone species—an animal critical to the health of an ecosystem—beaver ponds support aquatic creatures such as muskrats and river otters. They also attract a variety of reptiles, water fowl, insects, plants and mammals. This year, a pair of mallards raised ducklings in one beaver pond, says Wilde. Deer frequent the wetland areas, as do black bears. “The one thing I really notice is the moose. The moose just love those wet areas,” says Wilde. “There’s a bull moose, and he grazes the bottom of a pond, gets his head down in the water and picks stuff up from the bottom.”

Being a rancher, says Wilde, doesn’t solely mean growing livestock for human consumption, it also means being a steward of nature. “If we make things good for our animals, well then they’re good for all animals.”

Jay Wilde. Photography courtesy of subject.

Bringing beavers back

Human-caused climate change set another heat record in 2023, with the planet enduring what is likely the hottest year in 125,000 years, according to Climate Central. If landscapes weren’t fried under the scorching sun, floods washed away homes, farms, livelihoods and even lives. This summer, a record 46 million acres of tinder dry Canadian forests ignited, smothering the East Coast in choking smoke. The US also experienced a record number of billion-dollar climate-change disasters. According to the Joint Economic Committee Democrats, US wildfires cause damages from $394 billion to $893 billion annually, or from two to four percent of annual GDP.

The Bureau of Land Management views the beaver as a critical weapon of climate change mitigation. It works closely with state partners to promote the reintroduction of beavers across the US, believing the animals will have a significant impact on drought-stricken areas by “slowing the flow of water, increasing the retention of water, especially through those really hot dry summer months,” says Scott Miller, director of the National Aquatic Monitoring Center, a joint partnership between BLM and Utah State University. What is needed, says Miller, is to “capture hearts and minds” about this winsome and industrious creature.

With North America nearing a tipping point for environmental catastrophes, wisdom dictates that collaboration with beavers could bring us back from the brink.

Well Done! Good writing.

Excellent game

Be careful introducing a new species to local environments, it can go awry. Beavers were introduced to Patagonia with devasting results a few decades later. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/beaver-overpopulation-tierra-del-fuego

Ode to Beavers on Pecan Creek

After my wife and I bought our farm we ended a cattle grazing lease and started working with a beginning khatadin sheep farmer. The sheep avoid the wet riparian area adjacent to the creek that flows through my property. Willows and cottonwoods have started regrowing and this year a family of beavers have moved in. The only downside so far is I had to put welded wire fencing around the few remaining large cottonwoods to protect them. I’m looking forward to seeing how they impact the ecosystem in the years to come.

Fantastic article! Long live the beaver!