It’s the End of Food as We Know It—But It Doesn’t Have to Be

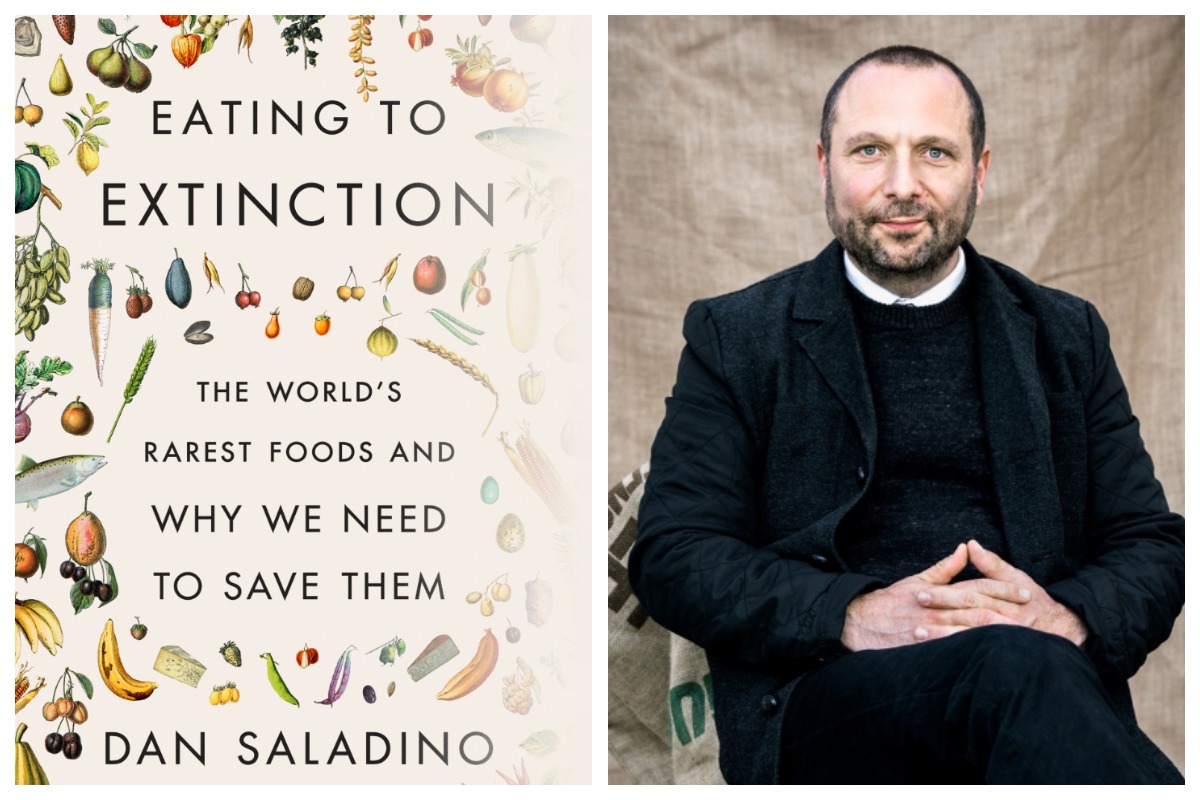

In his new book, Dan Saladino examines the ways in which multiple food species are going extinct and what can be done to prevent further loss.

It’s the End of Food as We Know It—But It Doesn’t Have to Be

In his new book, Dan Saladino examines the ways in which multiple food species are going extinct and what can be done to prevent further loss.

It's not too late to save our dying food species.courtesy of publisher; author photo by Artur Tixiliski.

It’s not hyperbole to say that there are a few crops that have altered the course of human history. The Cavendish banana. The navel orange. Genetically modified soybeans. They’ve all helped humanity solve the huge problem of feeding our ever-growing population. These crops, and others like them, were a massive benefit to us when we needed them.

But now, these same crops could be our downfall.

As British food journalist Dan Saladino writes in his new book, Eating to Extinction: The World’s Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them, there are thousands of crop species that either have died out or are at risk of going extinct. This is mostly because of choices people have made in the name of globalization and colonization. Along with creating plants that were more transportable, more hardy for harsh weather conditions or more resistant to pests, we’ve also ended up with just a handful of corporations in control of many of these plants. Saladino lays out a few of these dire statistics, noting that roughly 50 percent of the world’s cheese is dependent on starter cultures from one company. One quarter of the beers drunk in the world are produced by one company. Global pork production is based primarily on the genes of one breed of pigs. Just a handful of companies are in control of the majority of the world’s seeds.

As Saladino argues, those efforts have been helped along by legislation and government subsidies. “This is a political decision,” he says. “Governments are often worried and scared, rightly so, of food shortages and lack of food. But that’s a very short-term way of thinking.”

Thanks, in part, to decisions made with globalization in mind, the average diet is more homogenous than ever. It may not seem like it, because we’re surrounded by a false diversity every time we go to the grocery store. From tomatoes in January to 50 different boxes of cereal on the shelf, we’re surrounded by an abundance of food options. Your diet is likely ten times more varied than what your grandparents ate. And yet, those out-of-season January tomatoes are often just one or two strains available across the country. Those multiple boxes of cereal are all made with the same base of wheat or corn species.

“Of the 6,000 plant species humans have eaten over time, the world now mostly eats just nine,” Saladino writes. Of those nine, rice, wheat and maize make up 50 percent of all calories eaten in the world. “Add potato, barley, palm oil, soy and sugar, and you have 75 percent of all the calories that fuel our species.”

It was this revelation that prompted Saladino to write the book. He spent decades as a reporter for the BBC, and in that time, he traveled the world telling stories about food. During his travels, Saladino witnessed an increasing number of people talk about the crops they could no longer afford to grow or the species that were at risk of dying out. It came to a head during one trip to Sicily during the annual blood orange harvest. “I was being told by farmers that it was their last harvest,” he says, “that it was no longer financially viable for them to be growing this fruit that had been growing on the island for 1,000 years.” That led Saladino to Slow Food’s Ark of Taste, a foundation committed to promoting and saving local foods at the risk of extinction, through which he made further discoveries about our global food system.

In Eating to Extinction, Saladino invites the reader along on his trips across the globe, writing small vignettes from dozens of places, each focused on a different food. He examines multiple examples of grains, cheeses and vegetables that are at a tipping point on the world’s stage. At the same time, Saladino gives the reader a short history lesson, so we know how we ended up here. “After the Second World War, there were parts of Europe at risk of starvation, and there were concerns over famine in Asia,” Saladino explains. “Who can blame the crop scientists for trying to come up with solutions or quick fixes to produce more and more calories for a fragile population?”

The development of crops that were more transportable or more resistant to disease was inevitable in that situation, and it was arguably a good thing. The problem, Saladino says, is that momentum took over, and now, we’re hard-pressed to stop it. “It catches up with us, and we become locked into this system and the promise of abundance and cheap food. But as we now know, in terms of the environment and climate change, water loss, problems with soil, problems of nutrition…We know it was a success story at the time, and for many decades,” he says. “Now we are seeing the consequences of that success.”

Saladino argues that a lack of diversity in global crops is not only unhealthy for us but risky for the future of the plants themselves. “Monocultures don’t exist in nature. There’s a reason diversity exists,” he says. A mono-cropped acreage is less resilient and more prone to disease. Take the history-changing Cavendish banana. The variety is far and away the most popular worldwide, because it has a thick skin that protects the bananas in transport, and they can ripen while they’re being shipped. That means they can be picked early and arrive at their destination ready to be peeled and eaten. But the variety is also incredibly susceptible to a fungus, which could wipe out the Cavendish banana and tank a global industry.

So, where do we go from here? In order to save our food species, and help our overall health and resiliency, Saladino says we need to look at legislation that cares more about the long-term impacts of our food system and focuses on reducing our dependence on fossil fuels. We can do that by eating locally and discovering which plants have adapted to different parts of the world. “It took thousands of years for this interaction between humans, environment and animals to produce foods that flourished in a particular part of the world,” says Saladino. “Science and technology allowed us to, in a reductionist way, override that.”

Despite all of this, Saladino is eternally optimistic. He sees individual efforts and commercial changes as moves in the right direction. In his view, it’s both possible and plausible that we can become experts in our own local biodiversity and have that knowledge impact our decisions when it comes to what we eat. As Saladino writes: “We get the food system we pay for.”

The question now is, how much is our food system worth?

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Emily Baron Cadloff, Modern Farmer

February 1, 2022

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.