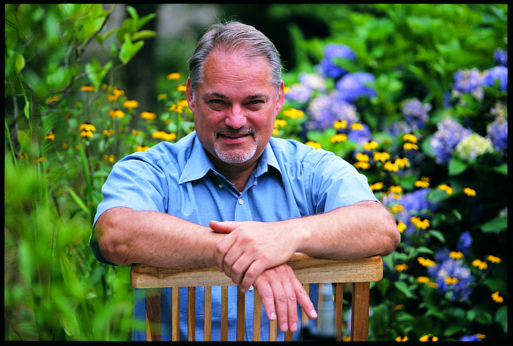

He’s keeping heirloom vegetables alive.

As personal and professional chefs become more interested in using locally grown and more flavorful produce, Weaver’s 85-year-old seed collection could change the way we eat.

Everyone knows what a watermelon looks like. It’s green and oblong, with dark green stripes. Inside, it’s dark pink, sometimes littered with black seeds and sometimes not. The rind around it is strong enough that it probably wouldn’t break if dropped from a couple of feet onto the grass. It’s strong and durable, but it hasn’t always been.

For a long time, William Woys Weaver thought that everyone’s grandfather collected seeds. “I just continued what my family had been doing all along,” he says. Weaver’s grandfather began the Roughwood Seed Collection in 1932 and grew it all his life. Today, his collection is not only the oldest collection of seeds in Pennsylvania but also the largest private holding of Native American food plants anywhere.

Stored on bookshelves in a dark archive room are hundreds of feet of tiny, carefully categorized seeds — and not just any seeds but special, very old ones. Weaver doesn’t just have a seed for corn; he has seeds for Oneida corn flour, one of the oldest and finest Native American flours that was used to feed George Washington’s starving army in the 18th century. He doesn’t just have russet potato seeds; he has about 100 varieties of potatoes, including a rare potato from Scotland that has red, white and blue patches on its skin.

“If we lose these seeds, we lose control of our own food supply, which was the situation for medieval serfs,” says Weaver. Most of the food we eat today — even much of the food grown in our own gardens — comes from seeds that have been genetically modified over time. On its own, that isn’t a bad thing. Take the watermelon, for example. Watermelons were heavily crossbred in the 20th century to make them easier to sell. At first, they were crossbred to be more resistant to pests, which also made them a little mealier. Then they had too many seeds, which could be crossbred out. They also kept breaking on trains, so they needed thicker rinds. The watermelon we have today is perfectly bred for transportation and mass consumption, but it wasn’t modified for taste.

An heirloom seed can be completely different in appearance, taste, texture and nutritional value than produce you might pick up at the grocery store. As personal and professional chefs become more interested in using locally grown and more flavorful produce, Weaver’s 85-year-old seed collection could change the way we eat. “We need biodiversity not only in our environment but also in the foods we eat,” says Weaver. “Heirloom seeds are nutritionally richer than commercial hybrids, even more so when raised organically,” he says.

Over the next few years, he hopes to expand to a climate-controlled facility with root cellars for biennials such as beets and turnips. Weaver’s goal is to maintain the genetic purity of these heirloom seeds so that they can outlast us and the flavors of our continent’s ancestors won’t disappear in favor of supermarket convenience.

Every once in a while, a family will send their seeds to Weaver — something special, historical and perfectly unique. The Roughwood Seed Collection promises to maintain the genetic purity of those seeds. “We don’t find seeds,” says Weaver. “The seeds find us.”

Loved the magazine ,miss going to my mailbox..

Thank you for providing this extremely valuable service..

Great article on a very important concept for us all! Hybridization is great for some mass production/transportation needs yet we usually lose big time on flavor and food value!!!

With the greatest respect to Farmer Weaver, he says that “Most of the food we eat today — even much of the food grown in our own gardens — comes from seeds that have been genetically modified over time”. No so sir, they may have been cross-bred, but the dreaded GM, Genetic Modification, is totally different.

am looking to plant some salsify this year, can you help me?

Home gardeners saving seeds

Very interested in Mr. Weaver’s work.

It is very valuable for all of us.

Wish my grandpa – a farmer- had thought to do the same.

Robin