An icon of enlightened farming in the corn belt ruminates on the origins of agriculture, nature's designs on the land - and a new kind of beer!

Wes Jackson

Long Root Ale is the first beer offered by Patagonia Provisions, a five-year-old offshoot of the outdoor clothing company. What’s truly notable about it, however, is that it is the first ever commercial food product made from Kernza, a new grain developed from a wild Eurasian wheatgrass. Kernza is a perennial plant, meaning it sprouts from the same roots year after year, unlike wheat and almost every other commercially produced grain, which are annuals that require replanting.

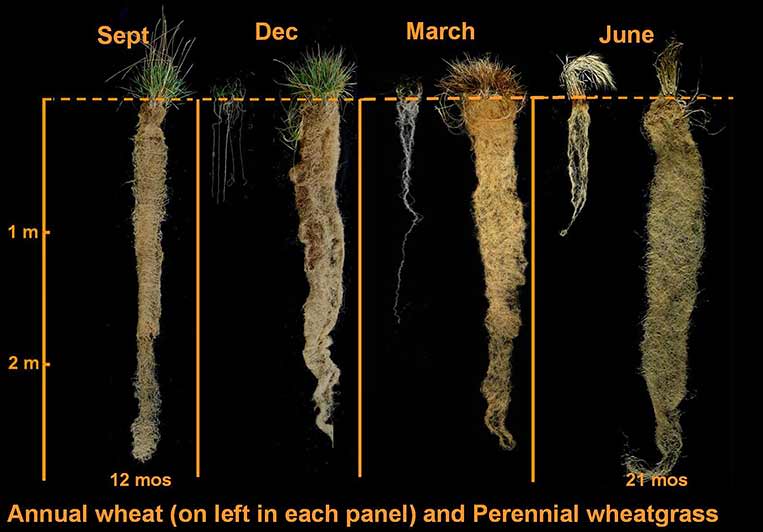

This is no minor detail, but an Earth-shattering paradigm shift, as Wes Jackson, the 80-year-old botanist behind Kernza explained in a recent conversation with Modern Farmer. Kernza’s 10-foot roots are more than twice as long as those of annual wheat, so the crop needs far less irrigation and fertilizer to thrive. Even more significant is that perennial Kernza plantings sequester immense quantities of carbon from the atmosphere, unlike the immense swaths of corn, soybeans, wheat and other commodity crops blanketing the earth today, which release carbon from the soil every time they are tilled for a new planting.

Tillage also destroys much of the biological activity in the soil, leaving it lifeless, robbed of its fertility, and susceptible to erosion in the wind and beating rain. As a result, much of the best topsoil in places like Kansas, where Jackson hails from, has been washed into rivers and streams, deposited in an eternal grave at the bottom of the sea.

In 1976, Jackson founded The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas to research ways to reverse the degradation of our agricultural landscapes. For 40 years, he has worked to breed a commercially viable perennial grain, a key component of his vision for a more holistic agriculture in which annual monocultures are replaced by perennial polycultures – mixtures of complementary crops that have the innate resilience and high biological productivity of natural ecosystems.

Modern Farmer: We hear you’ve recently retired after 40 years at The Land Institute. Congrats!

Wes Jackson: I’m not retired actually, I’m just not president of the organization anymore. I’ve got a backlog of writing that I’m catching up on. And I’m in the early stages of a new book.

MF: The Land Institute has developed several perennial grains, of which Kernza is the first to become commercialized. How widely has it been planted?

WJ: It’s still very limited. So far much of the acreage is for research purposes, but there are farmers growing it up in southern Minnesota for Patagonia. Besides beer, Patagonia wants to make some other food products with it; I don’t know exactly what yet.

Why do we keep insisting on introducing poisons to our land and our water? That’s the problem with genetic engineering. This is not using our heads when tinkering with nature’s arrangements.

MF: Why perennials?

WJ: With perennials you’re not tearing the ground up every year, so you preserve whatever has been going on below in the soil in terms of the bacteria, fungi, invertebrates, worms and so on – those are our workhorses below the surface. If they can stay in place, the crop is more efficient. You get all the services of nature that way. If you’re tearing up the ground to plant annuals every year, not only do you lose those services, you’re also going to have soil erosion and more fossil fuels are required to work the ground. We are trying to get agriculture away from the extractive economy and into the renewable economy.

MF: How do the yields of Kernza compare to wheat and other grains?

WJ: The yield is really low which is one reason why it’s not more widely planted. Through breeding we’ve increased the kernel size to 2 to 3 times the original size of the wild grain; it’s comparable to the size of wheat kernels in 1930.

MF: So it will be an ongoing process of breeding to develop a perennial grain that can compete with annual grains on an economic basis?

WJ: Yes, but it’s moving along quickly. When I first started working on this 40 years ago, I said this is going to take 50 to 100 years. The yields are lower now, but my bet is that in the long run perennial grains will out-yield annuals. Remember, the annual grains we have now have been 10,000 years in the making [since farmers first started breeding wild grains]. We’ve been at this less than half a century. So I think we are ahead of the curve.

MF: Why do you think we went down the path of annuals rather than perennials?

WJ: That’s a good question, which I think our scientists here have now answered. Here’s the story. Annuals tend to self-pollinate – that is, they accept their own pollen – which is akin to botanical inbreeding. In humans that’s a problem. We don’t expect our children to be mating with one another because of all the deleterious genes that produces [laughs]. We’ve run that experiment – look at the pharaohs, and some of the European royalty of the past.

But in plants it can be a good thing because you create lots of mutant genes, some of which will be useful for agriculture. Mutant genes provide resistance for what we call seed shatter, for example, which means humans can easily strip the grain off the plant without harming it. When you cross- pollinate annual grains you get lots of these useful new genes, but it’s also easier to breed out any mutant genes that you don’t want with the annuals.

We like to joke that if you are working on something you can finish in your lifetime, you’re not thinking big enough.

Perennials, on the other hand, tend to outcross, rather than self-pollinate. Mutations are still occurring all the time, but with outcrossing it’s harder to get rid of the genetic traits you don’t want and preserve the ones you do.

MF: So primitive horticulturalists couldn’t figure out how to domesticate perennial grains, but you have.

WJ: Yes, we figured out how to purge those undesirable traits from the genome. It’s partly because of our knowledge of genetics, and partly our computational power. That’s why our ancestors didn’t do it, and why we can now.

MF: When you give lectures, you often refer to the “10,000-year problem.” What does that mean?

WJ: We’ve been around for 150,000 to 200,000 years with a big brain, our 1,350 cubic centimeter brain. But we’ve had agriculture for only 10,000 years – since the wheat plant was developed from its wild ancestors in the Zagros mountains of Western Iran. That was the moment in which nature began to be subdued, plowed up.

So there was a dualism that developed – wild nature, with virtually no soil erosion, and then us with the plow. It’s been going on for 10 millennia. Now we have not only soil erosion, but chemical contamination of the land and water with fertilizers and pesticides and so on. According to the United Nations, we lose about 30 million acres of arable land per year worldwide to degradation and desertification.

MF: Do you think that genetic engineering could have a role to play in developing perennial grains?

WJ: In plants, perennialism is a way of life. There is no one gene for it; it is spread across the genome, so to speak. The genetic engineering approach is to create some trait like resistance to Roundup, so you can drench the countryside with herbicide like Roundup in order to kill weeds. Then you have a chemical out there that we haven’t evolved with. Glyphosate, the chemical in Roundup, is considered a probable cause of cancer.

MF: What do you say to those that look at genetic engineering as a way to produce more food on less land?

WJ: What, so we can put more grains into our cattle and pig welfare program? So we can have ethanol, which takes more energy to produce than you get from it? We can do a lot of stupid things in order to accommodate the economy rather than to meet the needs of the land.

MF: I take it you’re opposed to genetic engineering across the board?

WJ: We understand ecology and evolutionary biology, so why do we keep insisting on introducing poisons to our land and our water? That’s the problem with genetic engineering. You also end up with a bunch of weeds that are resistant to Roundup. So this is not using our heads when tinkering with nature’s arrangements. We are evolutionary biologists here at The Land Institute. We are looking to the way nature’s systems have operated over millions of years, not some Johnny-come-lately thing.

So far we have done what colonizing people do – we come in and take and do not pay much attention to tomorrow, or the next year, or the next century.

MF: It seems you are just as interested and concerned with the relationship between agriculture and culture. In fact, you wrote a book years ago called Becoming Native to This Place. What does that mean?

WJ: Most of us did not evolve on this continent, and we have to remember that biologically we are still basically hunters and gatherers. But for the last 10,000 years we’ve displayed our human cleverness with the plow and more lately with chemicals and fossil fuel machinery. So our presence on the landscape is, in a sense, alien. We are a species out of context, out of the context of what shaped us.

I’ve written that I think the discovery of America lies before us. So far we have done what colonizing people do – we come in and take and do not pay much attention to tomorrow, or the next year, or the next century. That’s not having a culture. That is simply engaging with the world, with the ecosphere, as colonizers. Take and go.

MF: In another book you talk about “consulting the genius of a place.” What’s the genius and how do you consult with it?

WJ: Think about what this continent was when Europeans got here. There were indigenous groups here, and they were cutting trees here and there, and they were using fire to manage the prairies for game, and so on. But they were not plowing. It was still mostly nature’s ecosystems – forests, prairies, alpine meadows. These ecosystems are what we call perennial polycultures, mixtures of many species of plants and animals that function as a whole. When we came to this continent we created the opposite of that – annual monocultures.

So what we’ve done at The Land Institute is start with the question, What was here? What was here in Kansas was native prairie. So what we’re trying to do is have those same processes of wild nature brought onto the farm. That means we need perennials, and we need to grow them in mixtures. That’s the genius. The genius is the prairie or the forest or the alpine meadow.

MF: Sounds lovely. And it’s a far cry from the mindset of most of agriculture today.

WJ: This is the problem with long-term solutions. When I said it would take between 50 and 100 years I was 40 years old. There aren’t very many people who want to make a commitment to something like that. We like to joke that if you are working on something you can finish in your lifetime, you’re not thinking big enough.