They say the beef smelled like an embalmed dead body. By the end of the scandal, it would irrevocably change how Americans dealt with their food.

But that alleged rank beef – along with a groundbreaking book – helped usher in modern food safety in the United States.

In 1898 the cry of “Remember the Maine,” a reference to the possible bombing of a U.S. battleship in Havana harbor, was whipping the country into a war frenzy. New York newspapers, especially those owned by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, helped rattle the sabers with lurid accounts of alleged atrocities committed by the Spanish in Cuba. The U.S. had been closely following the Cubans’ fight to free themselves from their colonial masters and when the Maine blew up under mysterious circumstances that February, killing 266 of her crew, it was only a matter of time before Spain and America would clash.

When war was declared in April 1898, the Army was ill-prepared for battle. At the time there were just over 28,000 available troops, but after a call for volunteers that numbers jumped by nearly 10 times, initially stretching supplies thin. Beyond this, there was little thought put into what changes would be required to fight in the tropics. Besides Cuba, the war would encompass both the Philippines and Puerto Rico. The men were issued heavy wool uniforms, had inadequate medical supplies, and rations that spoiled in the heat, forcing them to mainly subsist on canned beef that was stringy and tasteless at best and possibly sickened or killed some soldiers.

The commander of the Army, Gen. Nelson A. Miles, told a government commission investigating the handling of the war he believed the meat was “defective.”

The commander of the Army, Gen. Nelson A. Miles, told a government commission investigating the handling of the war he believed the meat was “defective.”

In Cuba, the troops ate the canned meat while in Puerto Rico the men were given a combination of canned beef and refrigerated beef, and it was this latter meat – 327 tons worth – that Miles was especially disturbed by, telling the commission the meat had an “odor like an embalmed dead body.”

“It was sent as food. If they wouldn’t have taken that, they would have had to go hungry,” he told the Dodge commission, which was named for Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge, who headed it up.

Miles believed the chemicals used to treat the meat were responsible for the “great sickness in the American army,” and said he had advised against the shipping of beef to Puerto Rico because there were adequate supplies available there.

He characterized the plan as an “experiment” for which “someone in Washington “was responsible. That person, he said, was The Commissary General of Subsistence, Brigadier General Charles P. Eagan.

“Reports were frequently sent in to [the Commissary General], but he seemed to insist that the beef be used,” said Miles.

Eagan vigorously defended his handling of the supplies during the war and of the quality of the beef in particular. Had he left it at that, things may have subsided, but the hot-tempered general instead went on a mellifluous tirade against Miles and called him out like only a Gilded Age gentleman could.

“He lies in his throat, he lies in his heart, he lies in every hair on his head and every pore in his body,” he began, just getting started. “I wish to force the lie back in his throat, covered with the contents of a camp latrine.”

Eagan heaped contempt on his superior officer, telling the commission that Miles should be barred from polite society.

Eagan’s lawyer called his client’s ranting “the natural outburst of a man suffering under an unjust accusation.” Eagan’s superiors called it “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.” He was court martialed and dismissed, but President William McKinley commuted the sentence and put Eagan on paid suspension for close to two years and then allowed him to retire.

The Dodge commission determined that there was nothing wrong with the beef and that the confirmed cases of food poisoning were due to some canned beef being mishandled.

The commission found that the refrigerated beef was not “subjected to or treated with any chemicals” and that shipping the beef from the U.S., rather than procuring fresh meat in Puerto Rica, “was wise and desirable.”

But the controversy wouldn’t die. Eventually a so-called military Beef Court (yes, there is such a thing as Beef Court) was convened with the task of trying to get to the bottom of the embalmed beef issue. In an investigation that lasted nearly as long as the war itself, the court came up with similar findings as the Dodge commission, concluding that Miles had made unjustified allegations concerning the refrigerated beef. The court also chastised Eagan for procuring thousands of pounds of canned beef that was “practically untried and unknown.”

Perhaps the embalmed beef story would have ended there but for two events: the publishing of “The Jungle,” – a muckraking novel written by socialist journalist named Upton Sinclair – and the assassination of McKinley, which elevated Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency.

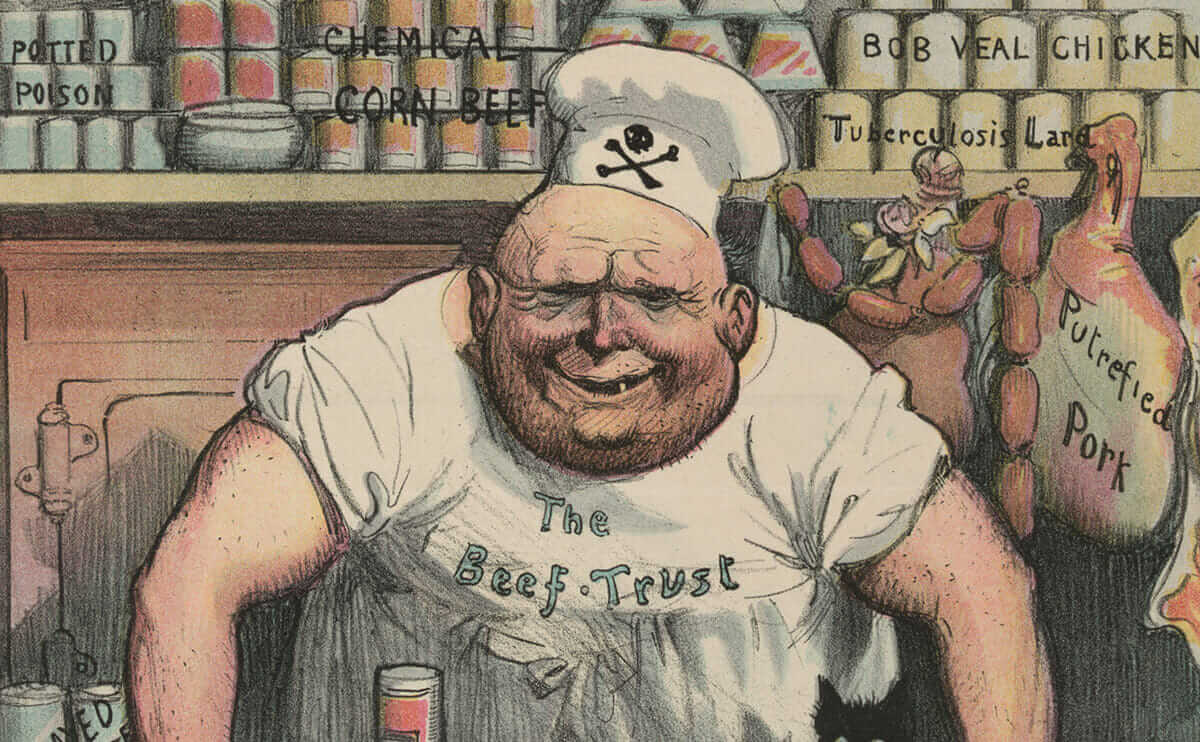

“The Jungle,” published in 1906, was intended to throw light onto the deplorable living and working conditions of America’s immigrants, but instead it became a sensation for exposing the unsanitary conditions of Chicago’s meatpacking plants. Sinclair’s stomach-churning descriptions of the industry’s practices stuck in reader’s minds more than the storyline of a Lithuanian man and his family trying to survive under the harsh conditions typical of the era.

“I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach,” Sinclair would later say. “I realized with bitterness that I had been made into a ‘celebrity,’ not because the public cared anything about the workers, but simply because the public did not want to eat tubercular beef.”

Many of the descriptions of industry practices, which included allowing meat to be stored in rooms where water would drip over it and rats would defecate in great mounds upon it, came from Sinclair’s first hand experience. Before writing the novel he had spent seven weeks working undercover at a plant for a series of articles for a socialist newspaper.

Roosevelt, who had fought in the Spanish-American War before becoming U.S. president, had been forced to eat some of the “embalmed beef” and believed it to be tainted. He was also disgusted by Sinclair’s description of the meat packing industry’s practices and looked further into the author’s allegations. A report by Labor Commissioner Charles Neill and a social worker named James Reynolds, who Roosevelt had sent to inspect Chicago’s meat packing plants, confirmed most of Sinclair’s claims.

Roosevelt pushed Congress to act, and in 1906 the Pure Food and Drug Act as well as the Meat Inspection Act became law, forever changing the way America dealt with its food.

If I can write like you, then I will be very happy, but I can’t write like you, where is my luck, in fact people like you are an example for the world. You have written this comment very beautifully, I am very glad that I thank you from the bottom of my heart. anupatel

If I can write like you, then I would be very happy, but where is my luck like this, really people like you are an example for the world. You have written this comment with great beauty, I am really glad I thank you from my heart.