How agriculture and conservation are coming together for the survival of the endangered monarch butterfly.

From behind the driving wheel of his pickup truck, Don Guinnip turned the ignition key, flipped on the A/C and immediately rolled down the windows. The sticky, midsummer air barely budged even as cool air from the dashboard vents mixed with the breeze flooding the cab. A few miles down the narrow road from his Marshall, Illinois family farm, founded in 1837, he stopped and pointed. There, at the base of a utility pole under a tethered wire, was a clump of thriving common milkweed, reaching three or four feet toward a partly cloudy sky. “It’s protected there,” the 70-year-old farmer says.

By now, the milkweed has matured. Under the power lines, milkweed has been left untouched by a farmer’s last mowing pass. The stems are sturdy and the deep, green leaves, arranged in opposite pairs, are broad and thick. At the top, clusters of small, pink flowers nearly form a sphere—a beacon for monarch butterflies along a crucial, yet disappearing, migration path.

All around, for hundreds of acres, soybean fields blanket the black soil in this southeastern Illinois farming region. It is one of the staple crops the Guinnips have grown for five generations. Alongside the milkweed, soybeans, too, are thriving.

Scenes like this—clumps of milkweed dotting grasslands that encase crops—are now the norm. But up until the mid-1940s, before herbicides were introduced to commercial agriculture, milkweed grew relentlessly in croplands. It was invasive. It impacted crop yields to the point where farmers like Guinnip recall the labor-intensive chore of pulling milkweed from the fields as a child.

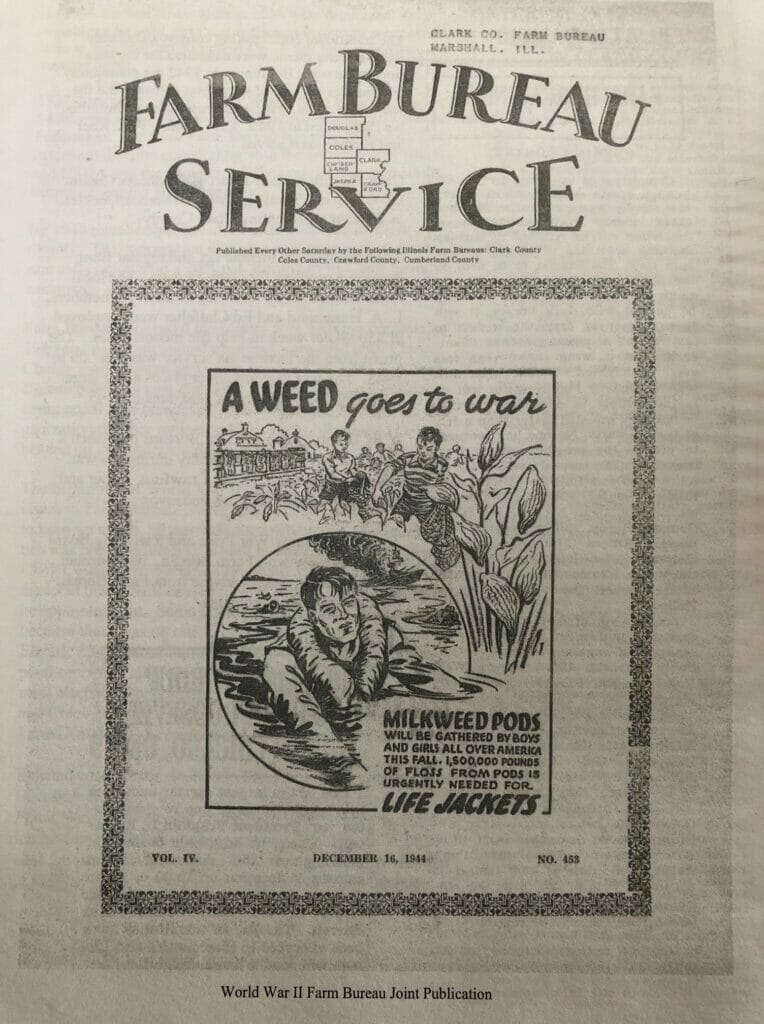

Illinois Farm Bureau Service encourages children in rural farming communities to pull milkweed for the production of “urgently needed” life jackets during World War II. Courtesy of the Clark County Farm Bureau.

During most of the 19th and 20th centuries, it was abundant in crop fields. At first, farmers opted for manual weeding with hand tools such as hoes and draft animals. In fact, images of children pulling milkweed from farm fields were prominent back in Clark County, home of the Guinnips’ farm. As early as 1944, the Clark County Farm Bureau Service posted advertisements promoting local children pulling milkweeds for the floss found in the seed pods that were “urgently needed” for life jackets during World War II. “A Weed goes to war,” it read.

After that, tractor-based mechanical cultivation to remove weeds became the norm for keeping the invasive species at bay. But rather than killing off the milkweed, this type of removal, according to researchers, often stimulated regrowth later in the growing season.

With Milkweed Gone, So Are the Monarch Butterflies

The common milkweed is the main plant species that the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus, needs to survive. And the species is disappearing at a rapid rate. If milkweed ceases to exist, scientists say, so, too, will the iconic monarch butterfly.

The perilous state of milkweed matters to farmers like Guinnip because, he says, “We don’t want to burden the environment when we don’t need to.”

As it turns out, the decline of milkweed threatens more than monarchs. Such threats have a cascading effect that eventually affects humans, as one-third of the nation’s food production is dependent on pollinators like monarchs.

Every spring, millions of North American monarchs take flight from the fir forests of Mexico’s Central Highlands and begin migrating north and east. Along the way, they seek milkweed to lay their eggs. Monarchs are the only butterflies known to make two-way migrations, similar to birds. It takes several generations to complete each leg of the journey, according to the US Forest Service. The reasoning behind the 3,000 miles traveled annually—across their summer breeding grounds of the lower eastern and western US and into southern Canada to their overwintering grounds in Mexico—remains a mystery.

In 1983, one of the world’s most spectacular natural phenomena—the monarch migration—was listed as “endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), with reasons pointing to humans. Threats to their migration included changes in land management practices, leading to a demise in trees where monarchs overwinter. Monarch butterflies also died after encountering pesticides that were applied to fields to control nuisance insects yet had negative consequences for both good and bad ones. Those that did survive had difficulty finding food, as the milkweed they rely on was killed off by conventional agriculture’s use of herbicides.

Nearly three decades later, in 2020, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) declared that listing the monarch as “endangered” was warranted, but it stopped short of doing so because of higher priority species. Its endangered status is reviewed annually. Last month, the IUCN placed the monarch butterfly on its Red List of Threatened Species as Endangered, threatened by habitat destruction and climate change. One month prior, in June, the first-ever Monarch Butterfly Summit was held in Washington, DC. There, the Department of Interior awarded $1 million to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s (NFWF) Monarch Butterfly and Pollinators Conservation Fund for conservation efforts as well as supporting the FWS efforts to establish a Pollinator Conservation Center.

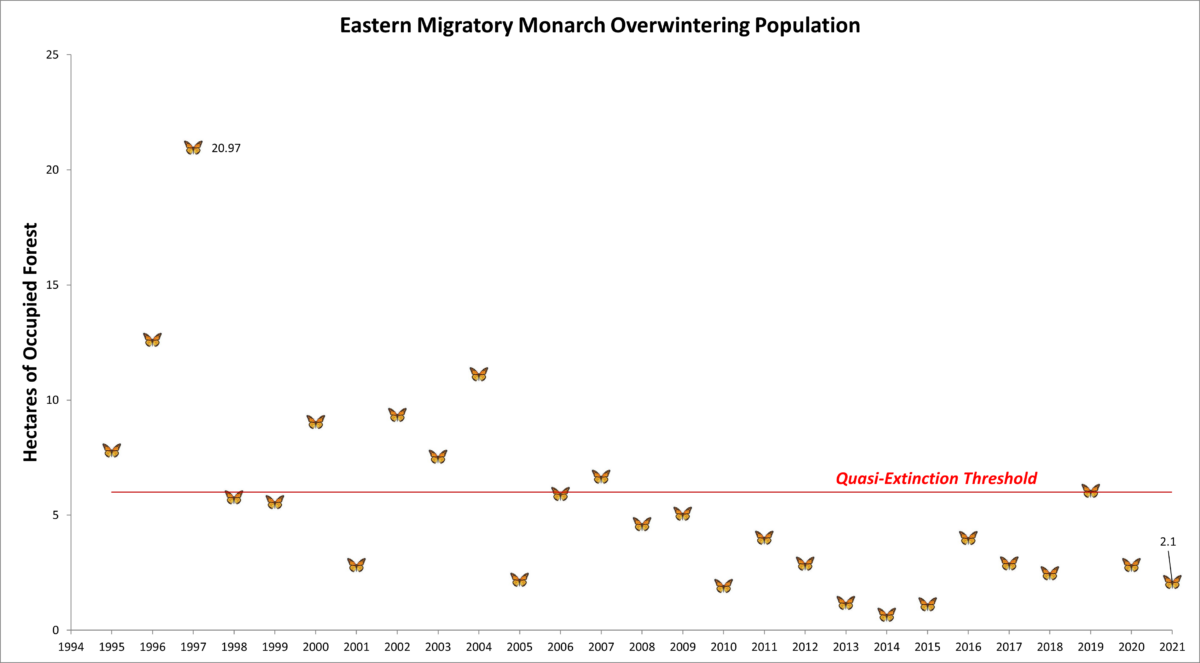

Eastern migratory monarch overwintering population graph by the Center for Biological Diversity.

The threats to monarchs are plenty: logging in its overwintering habitat, lost nectar sources, exposure to insecticides, climate change and loss of breeding habitat are all factors in its decline. Increasingly, evidence shows a major contributor to the recent decline of monarchs (around 80 percent of the population since the mid-1990s) is the loss of common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, as a breeding habitat in the Midwest. Researchers discovered milkweed growing in corn and soybean fields supported more monarch eggs and larvae than those growing in other areas.

Presently, most remaining milkweed in the Midwest is found in perennial grasslands at roadsides, on old fields, in parks and in conservation reserves. Monarch caterpillars require milkweed to grow into butterflies, feeding on more than 100 species of the plant across their flight path. Female monarchs only lay eggs on milkweed. It is estimated that there is an 80-percent probability of population collapse for the eastern monarch within 50 years, according to the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The monarch population is measured by the amount of forest hectares they populate when overwintering. The numbers, however, keep moving in the wrong direction. Earlier this year, data from the Center for Biological Diversity showed the monarch butterfly population dropping below the “quasi-extinction threshold” beginning in the late 1990s. In 2021, the population dropped 26 percent from the previous year’s count.

To respond to the loss, scientists and conservationists are researching how to rebuild milkweed populations with calls to restore 1.3 billion to 1.6 billion milkweed stems in the Midwest alone.

What Was Once a Nemesis Now is Necessary

In Carmi, Illinois, about an hour south of the Guinnip family farm, Don Duvall, a fourth-generation and retired farmer, has witnessed the evolution of milkweed on his 2,500-acre family farm. He grows corn, soybeans, wheat and some specialty crops, but it was milkweed that Duvall vividly recalls battling in his youth when he spent long summer days hoeing it from beanfields. The monarchs didn’t stand out.

“I took [monarchs] for granted because they were around,” he says.

Continuing to motor down the narrow farm road in Clark County, Guinnip points out the steep diving aerial motions of a bright yellow crop duster off in the distance. Since the 1990s, more than 90 percent of corn and soybean production has switched to transgenic herbicide-resistant crop varieties—a genetically engineered crop seed created to be resistant to the herbicide glyphosate. Fields sprayed with broad-spectrum herbicides have resulted in a 40-percent loss of milkweed from the Midwest.

“It’s one of the unintended consequences of the good job that farmers are doing in weed control,” Duvall says.

In 2015, when BASF, a German chemical company, promoted a program that provided more than 35,000 milkweed stems to farmers in an effort to establish milkweed on grasslands, Duvall signed up for it. The very weed Duvall fought for decades—his childhood nemesis—he was now planting.

“That seems almost ludicrous!” Duvall says, recalling the logic at the time.

Milkweed was planted in filter strips, the land next to drainage ditches bordering crops. Duvall even planted it as landscaping in his yard. The conditions for milkweed aren’t hard to achieve; the plants thrive in poor, dry soil in full sun.

Duvall watched and waited. Soon, the monarchs came.

A monarch caterpillar feeds on a species of milkweed planted in the backyard of fourth-generation, southeastern Illinois farmer Don Duvall. Photo by Don Duvall.

The loss of milkweed in Midwest crop fields shifted monarch habitats to perennial grasslands like the ones found along Duvall’s farm, as well as in parks, reserves or transportation rights-of-way. Because grasslands differ from agricultural fields (they are subject to mowing for agricultural safety and aesthetic reasons), researchers say understanding the differences may be key to stabilizing the monarch population.

This shift is unfolding all around Guinnip’s farmstead community. As his pickup approached an Interstate 70 overpass, Guinnip slowed down. With one eye on the road ahead and one hand steady on the wheel, he motions with his free hand toward the grassy right-of-way along the interstate as cars speed past below. Again, he points to a clump of milkweed. This time, it’s a large group; it’s thriving. In the truck, he pauses, and says with an optimistic tenor, “There’s something to this.”

Conservationists and Farmers Work Together

Across the country in Washington State, Eric Lee-Mäder spends much of his time monitoring the monarch butterfly. The self-described farmer-conservationist serves as the co-director of the pollinator conservation program at Xerces Society, a wildlife conservation nonprofit. He monitors private sector partnerships with some of the largest food companies on earth, including General Mills and Nestle, and focuses on integrating pollinator habitat back into the supplier farms that food companies source ingredients from.

“Monarchs have been a huge focus for us,” says Lee-Mäder, noting a strong nexus between the presence of monarchs and milkweed in agricultural lands. Since 2008, Xerces has supported the restoration of one million acres of pollinator habitat in agricultural landscapes nationwide.

Back in Illinois, in Guinnip’s Clark County, this is playing out in tangible ways. With the crop duster plane flying closer overhead, the farmer pulls off the road and onto a tall, grassy shoulder and points the pickup in the direction of a meadow. At first glance, the meadow has an air of nostalgia to it. There are acres beyond acres of blooming yellow, white and pink wildflowers set against a canvas of varying shades of green until it meets the treeline. It’s like the landscape has always been there.

But it hasn’t.

Wildflowers are in full bloom in a designated pollinator plot in Clark County, Illinois. Photo by Jennifer Taylor.

The picturesque scene is the latest evolution of an area farmer’s land—the result of a partnership program like those Lee-Mäder describes. This is a pollinator plot, Guinnip says, with thousands of acres planted exactly for that purpose. Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana and Iowa all have USDA incentive programs to help offset the costs of monarch habitat restoration work. This wild-by-appearance plot, surrounded by acres of manicured crops, tells another kind of truth about where agriculture and conservation stand today—that they need each other.

When Duvall looks back on his career, he doesn’t recall an epiphany that prompted him to suddenly bring back milkweed. It was, he says, a gradual awareness that he and other farmers gained, particularly when they learned of a 2006 University of California at Berkeley study that found that one-third of the world’s food supply relies on pollinators. That captured the attention of the agricultural world.

“Agriculture as a whole wants to be proactive to keep the soil health and Mother Nature in balance,” Duvall says.

Scientists continue seeking solutions. One Michigan State University study recently showed targeted mowing of milkweed in grasslands during specific times of the growing season produces milkweed stems that are attractive to egg-laying monarchs and harbor fewer predators. Yet, Lee-Mäder notes, without the supplementation and protection of milkweed, mowing alone won’t cut it for the monarch. “It’s not likely to reverse course for us,” he says.

He believes farmers with strong conservation ethics would be compelled to take action on their grassy spaces. Without conservation, agriculture ceases to function and ceases to exist. While it hasn’t always been immediately obvious that biodiversity bolsters agriculture, it clearly does. Without milkweed, without other wild plants, the landscape loses not only the monarchs but other linkages to the system.

“What happens to the majority of our songbirds that feed primarily on insects during at least one of their phases of their life?” Lee-Mäder asks. “Conservation and agriculture are kind of like Lincoln Logs. If you start pulling logs out of the middle, eventually the structure collapses.”

Fifth generation farmers Susan and Don Guinnip from southeastern Illinois stand in front of milkweed planted in their backyard. Photo by Jennifer Taylor.

Turning down Guinnip Road, the namesake throughway that leads back to his house, Guinnip ponders the role of farmers in conservation. He feels strongly that the contributions farmers make should be thoughtful, but also voluntary and without the threat of regulation. When his family first came to Clark County, it was with the intention of preserving the land. But it was also to make a living.

At the end of a long day on his 950-acre farm, Guinnip and his wife, Susan, often settle in on their back patio. There, they enjoy dinner and take in the full beauty—bees, a hummingbird and, at one point, a monarch floating from the milkweed to other blooms in their backyard. Ultimately, Guinnip believes there needs to be common ground to reach a balance between human beings and Mother Nature.

And deep down, this: “Farmers are the first environmentalists.”

Jennifer, excellent article. But there is one thing missing: A call to action … I represent the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, the USDA incentives you were mentioning fall under our agency. And it’s not just a few midwestern states. I am in CA and we have incentives for farmers to create monarch habitat.

So, please update with a call to action. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/national/plantsanimals/pollinate/?cid=nrcseprd402207

Thank you.

As a farmer in Ontario, I am concerned with the low number of Monarchs that have shown up in my area this year. I was able to walk through my back 40 in years past and see hundreds of Monarchs floating over my fields.This season I am fortunate to see two or three in an afternoon. Because of my concern, I stopped summer fallowing the area I was going to plant to wheat this fall. The milkweed have rebounded wonderfully. Last year I started raising Monarchs from eggs collected from Milkweed from a pasture that I clipped,, as I realized… Read more »

My daughter got interested in monarch conservation as a kid, so we gathered milkweed pods and planted alongside the house. We now have a dozen or so plants. This year for the first time, we have found 3 monarch caterpillars! We carefully gathered the stems and she is nurturing them. We helped 3 this year. Hopefully this will multiply exponentially!

Where can we please get seeds to help spread milkweed?

As usual it is up to the private citizens of this country to restore natures balance and undo the devastation that our government and Industry giants have caused. It is encouraging to see some people getting involved in this. There is so much work to do. Support nature and continue to find the balance that renews our lands fertility.

How do I get sponsorship to purchase land for a Monarch Way Station?

I am happy to report that I had 6 monarch caterpillars on my dill plant I have seen more monarchs in my state in SE Michigan

I love this article on the monarchs. I have some milkweed this year and I do see an occasional monarch and other butterflies as well. I have lots of bees on my flowers and I only mow my grass every other week and I do not fertilize my lawn. We also have no mow Mayand I participate in that and I hope to plant more milkweed next spring that I will be ordering this fall.

I’m a cattle farmer and the reason why they pulled out the milkWEED is because it is poisonous to livestock and it spreads like wildfire. Many farmer need hay bale for they livestock to survive winter. My retired neighbor planted milkweed in his property and has spread to my property and we had to lose the hay that we normally would use for our cattle. So now when winter comes we might have to sell because we will not have enough food for them. And like the article says it’s thrives even in poor soil. Sad to said but it… Read more »

I am about to be homeless and need a job. Would be willing to help the cause. Raised monarchs as a kid.