Biden Bets the Farm on Climate

The president’s plan for American agriculture is politically risky and scientifically debatable. It also may be his best chance to succeed where Obama failed.

Biden Bets the Farm on Climate

The president’s plan for American agriculture is politically risky and scientifically debatable. It also may be his best chance to succeed where Obama failed.

The Biden administration has proposed creating a carbon bank for agriculture.by john smith williams on Shutterstock

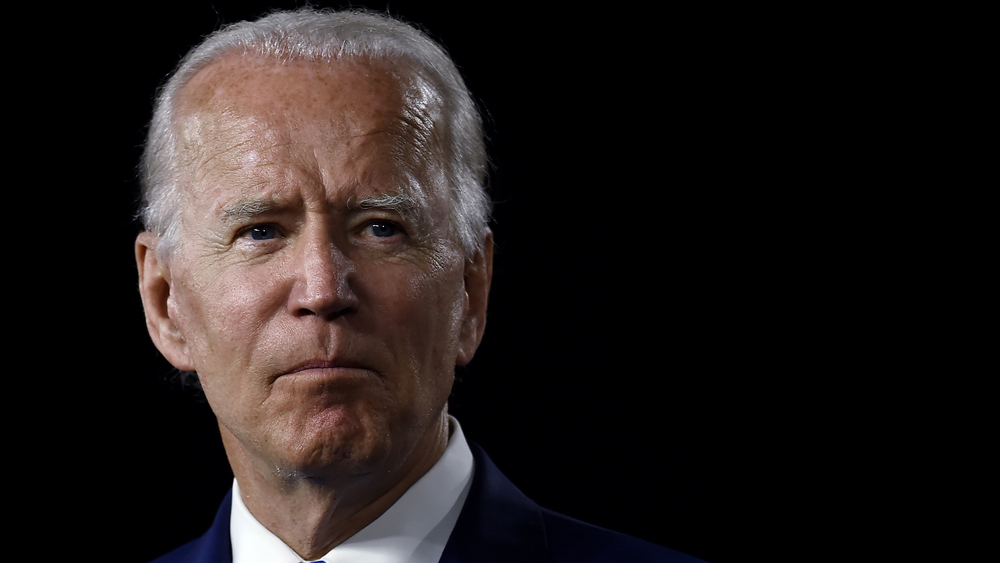

President Joe Biden has made no secret of his grand plans to tackle climate change. Before he even took office, he’d assembled a team of experienced climate experts to serve in his cabinet and spoke openly of a net-zero emissions future. Within hours of his swearing in, he’d formalized plans to re-enter the Paris climate accords. And within days, he’d made climate-related pronouncements covering everything from new federal oil leases (now on pause) to the government’s fleet of cars and trucks (soon to be all-electric).

Along the way, he and his team have made it abundantly clear that American farms will be fundamental to their efforts. Biden’s advisors quickly identified the US Department of Agriculture as a “lynchpin” of any climate strategy. The president predicted that the United States would be the “first in the world” to achieve net-zero emissions from its ag sector, which currently accounts for an estimated tenth of total US emissions. And former and future Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack declared agriculture “the first and best place to begin getting some wins” on climate.

But where, exactly, does the new administration believe those victories will come from? The available evidence points to one place in particular, a new “carbon bank” that would pay farmers, foresters and ranchers to store carbon in their soil through regenerative agriculture and other climate-friendly techniques. The plan aims to turn vast swaths of America into massive carbon sinks, helping to partially offset the nearly 7,000 megatons of greenhouse gases the US emits each year.

Success, though, is anything but guaranteed. Among the most pressing concerns: The science behind the bank remains unsettled. Its creation is already facing challenges from Congress and could potentially see more in court. And all the while, the program itself would be exceedingly complex and difficult to administer—and likely only grow more so if it lasts long enough to scale up. The list doesn’t end there, either.

For Biden, though, any potential pitfalls may pale in comparison to the possible payoff. In addition to pushing US agriculture toward zero emissions, the bank could also open the door, however narrowly, to the type of sweeping climate action that his old boss was never able to achieve, namely an economy-wide cap-and-trade system. Momentum to put a price on carbon, long a goal of environmentalists, has been missing in Washington since the last serious attempt to implement it died a slow death during former President Barack Obama’s first term.

Such a reward doesn’t come without risks, however. If the bank fails, either at the hands of partisan lawmakers in Congress or farmers in the field, it could irrevocably undercut Biden’s larger climate agenda while it’s still being implemented. The damage could last well beyond his presidency, too, dooming the prospects of any carbon-pricing scheme in the US for another decade, if not longer—time, clearly, that the world doesn’t have.

Getting Creative with the CCC

Biden has yet to officially call for the creation of a carbon bank, but his team at USDA has begun to publicly outline a plan. At its center is the Commodity Credit Corporation, a little-known financial institution created by the federal government during the Great Depression to help struggling farmers. Historically, the USDA has used the CCC as a way to prop up farm income with payments or loans to farmers when a major commodity crop such as corn or soybeans is damaged by natural disaster or disease. Like most things in Washington, though, that changed significantly under Trump. Under the former president’s agriculture secretary, Sonny Perdue, the USDA used the CCC as a vehicle to funnel billions in federal aid to American farmers who were hurt by Trump’s trade wars and later the coronavirus pandemic. CCC payments ballooned to such a degree that they accounted for an estimated 40 percent of all US farm income in 2020.

Biden’s team believes the way the agency used the CCC under Perdue cleared the way for Vilsack to get creative, too. As Robert Bonnie, a deputy chief of staff and senior climate adviser at USDA, put it during a virtual roundtable hosted by the Meridian Institute earlier this month: “Carbon is a commodity right now and the CCC was built to help think about how we stabilize that.”

Under the current plan, the USDA would use the CCC to pay farmers for every ton of carbon they are able to sequester in their soil by using cover crops, conservation tillage or other climate-friendly measures. Those payments would effectively create carbon credits, which the USDA would then sell to corporations looking to offset their own emissions. The bank would provide the agriculture sector with guaranteed per-ton prices for carbon sequestration, while also serving as an auditor to ensure that such practices are producing the desired reductions.

The plan’s appeal is easy to see for a president eager to get the ball rolling. Since the administration believes it can create the bank on its own, it won’t need to wait for permission from Congress, a legislative body historically unable or unwilling to address global warming in any meaningful way. The White House already appears to have some buy-in from powerful farm interests, a group that has been hostile to previous large-scale climate efforts. Armed with industry support and strong early returns, the thinking goes, maybe—just maybe—congressional Republicans will have no other choice than to support the bank once it is proven both successful in practice and popular with a key GOP voting bloc.

Counting Carbon

But bipartisan support for the carbon bank in the future may need to begin with scientific certainty in the present—something notably missing at the moment. The benefits of regenerative techniques such as planting cover crops or using biologically enhanced compost are well established by now. But there’s a big difference between knowing something works and knowing just how well and for how long it does so. The exact amount of carbon reduction such techniques achieve, meanwhile, will vary not just from farm to farm but from one part of a farm to another part of that same farm.

Getting an accurate measurement and putting the right price on it will be crucial. Already, environmental groups are worried that carbon-intensive industries will use purchased carbon credits to continue their polluting ways. But the reality could be even worse if it turns out the estimated sequestration doesn’t match real-world reduction—either because less carbon than expected is being captured by the soil through photosynthesis or because it doesn’t stay there for long.

An environmental research organization called the World Resources Institute detailed such scientific unknowns last year. Among the group’s concerns are the possibility that no-till farming may not be as effective at sequestering carbon as previously thought—and even if the technique does suck significant carbon out of the atmosphere, such benefits would only be temporary since the bulk of those farmers still plow their soils every few years anyway, releasing much of that stored carbon in the process. Meanwhile, if a farm changes hands, the future owner could decide to abandon any climate-friendly efforts, again putting sequestered carbon back in the atmosphere.

For critics such as Robert Paarlberg, an associate in the Sustainability Science Program at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, all those variables look like a giant red flag, especially when you factor in the support of an industry that worked so hard to oppose Obama’s climate efforts. “The closer you look at carbon farming,” he recently wrote in Wired, “the more it comes to resemble a sweet deal between Big Ag and corporate America to promote a painless and uncertain climate solution while tapping into public money.”

Even if the USDA can thread the needle and keep the industry happy while still holding it accountable, the department will still have plenty of other implementation challenges. New polling from Purdue University suggests less than a third of American farmers are currently aware of existing opportunities to sell carbon offsets directly to private companies—and less than a quarter of those that know are actively working toward doing so. The average American farmer is in their late 50s and nearing retirement—not exactly a demographic you’d expect to be eager to radically change how they do business.

Educating farmers about the carbon bank will take serious work from the USDA. So, too, will ensuring that Black farmers and other disadvantaged groups even have access to the program—a low bar that the USDA has sadly failed to clear throughout much of its history. Vilsack himself has faced serious criticism about his record on race during his first tour of duty at the USDA. He’s vowed to make addressing the department’s legacy of racism a priority during his second, but critics—including some congressional Democrats—will rightly want to see significant progress from the outset. Without it, the bank’s “success” wouldn’t extend to the entire farming community.

Cap, Meet Trade?

The CCC has the authority to borrow up to $30 billion at any one time, but the USDA would likely start small. A memo tied to Biden’s transition team, for instance, imagines a conservative scenario in which the department devotes $1 billion to start the bank—an investment that could buy 50-megatons worth of carbon reductions in a world where it was paying farmers $20 per ton—and then scales up from there.

The bank would become an initial middleman or marketplace of sorts, where carbon-negative farms and carbon-positive companies are trading credits. While Biden and his allies have been careful to brand their idea as “voluntary,” they’ve also suggested they’re generally open to “enforcement mechanisms” as part of their climate efforts. It’s not hard, then, to see the logical next step once voluntary trades at the bank are in full swing: a cap on emissions.

Congress, however, would need to create the cap, something nearly unthinkable at the current moment in time given Republican leaders—along with the most watched cable news channel—by and large continue to deny the reality of climate change and need for large-scale action. For now, though, the bank would be a start.

Lessons from Obama

If Biden decides to approve the bank, he can expect almost immediate pushback from a Republican Party that has already made it clear that it won’t afford the same executive flexibility to the current president that it did the last one.

Already, the top Republican on the Senate Agriculture Committee, John Boozman, has voiced his opposition to using the CCC to create a carbon bank. “I feel like that’s outside of the range of their ability to do that without legislation,” the Arkansas senator told reporters earlier this month following Vilsack’s confirmation hearing. Boozman added that he’s received legal advice suggesting the bank is a non-starter. “They might have other legal advice,” he said of the USDA, “but that’s something that we’re going to have to come to terms with.” Even if Republicans can’t stop Vilsack from starting the bank, the simple threat of political and legal gridlock could create enough doubt to become self-fulfilling, with those farmers who crave financial certainty staying on the carbon sidelines.

Hill Democrats, meanwhile, have suggested they’re ready to work with the administration. But lawmakers tend to be a possessive bunch who don’t like being left out of the process even if the ones running it share their goal. At the very least, they will want to be kept informed every step of the way. At a virtual roundtable earlier this month, for instance, the Democratic staff director for the House Agriculture Committee sounded a distinct note of caution. “I think members of Congress … are going to have a lot of questions,” said Anne Simmons at the event hosted by the Meridian Institute. “It’s been 12 years since we’ve really had this debate in earnest,” she added, in reference to the Henry-Waxman cap-and-trade bill that passed in the House in 2009, but then crashed into GOP opposition in the Senate. “There are a lot of new members, a lot of new staff, a lot of education that we’re going to have to do on our end,” Simmons said.

Biden, of course, is familiar with congressional and partisan gridlock more than most. As vice president, he had a front-row seat as the GOP did everything it could to undercut Obama’s climate agenda, first by blocking congressional action on cap-and-trade and then by fighting executive regulatory action on climate change. Importantly, however, Biden also watched as Obama was able to scratch out a few smaller wins along the way.

Of particular note were new fuel economy rules for automakers, which turned out to be one of the most significant climate actions taken by Obama during his eight years in office. You don’t need to squint to see the similarities between the auto rules, which attempted to rescue carmakers from their own worst impulses, and Biden’s ag plan, which could do the same for American farmers. Like the carbon bank, Obama’s auto rules relied on executive authority, were based on imperfect and incomplete science, faced challenges in Congress and the courts and ultimately secured buy-in from an industry under duress.

This late in the climate game, however, Biden will have to aim far higher than his old boss. To get there, though, he’s going to need to find some new and unlikely allies. Betting the farm, then, might be incredibly risky—but it also may just be his best chance.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Josh Voorhees, Modern Farmer

February 15, 2021

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreShare With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Mind-Boggling BS, Now we need a Carbon Monitoring CZAR and some Smart inventor to invent Carbon Monitoring equipment and a plan to ensure that Farmers are paid Commensurate to the amount of Carbon they are Capturing per acre and a chart to decide how much per acre they will be paid along with a Vetting system (Because the Democrats are so prone to vetting everything except Illegal Aliens) to prove the Farmers are accurate in their reporting and a Government Funded Organization to Monitor the Organizational Forms the Farmers must fill out and submit to the Agency that will disburse… Read more »

The proposed Carbon monitoring systems and organizational developing systems shouldn’t cost more than a few Billion Dollars give or take a million or so and should be up and running by 2025 or 2030, somewhere around there depending on who rigs the Elections in years to come and don’t forget the White House has a “Pen and a Phone” No matter who occupies it! (Sarcasm abounds)

Perhaps mastery of planet-friendly food production is better than the article suggests. The range of agricultural carbon practices is extensive Infographic: Why Farmers Are Ideally Positioned to Fight Climate Change – Inside Climate News Conservation Agriculture | Project Drawdown How to Sustainably Feed 10 Billion People by 2050, in 21 Charts | World Resources Institute (wri.org) Some practices are essentially proven, e.g., biochar, and success of many is closely linked to conditions: soil, climate, past tillage, etc. Mastery is growing rapidly through research and field studies at USDA, U.S. Universities and firms, and abroad. The list of representative governance options… Read more »

It was touched on in the article but not fully expanded- how does this plan work for small farmers in comparison to bigger agricultural industry farms? Would it be damaging the immediate income of the small farmers to take on part of their field for carbon banking? Is it even possible for them to do so or will there be an economic buy in that makes it too steep for an individual to afford without some additional help? I guess my question can be summed up as does this allow big agriculture to just take a greater market share?

I am a full-on soil carbon advocate. For those who have little understanding of farming systems world-wide agriculture is on the cusp of a technical change, elimination of tillage, as best we may. Tillage and the resulting erosion and its slow but steady reduction of living soil qualities has torn-away 30 to 40 of our heartland top soil. This condition points what many believe as an un-ending cornucopia of perpetual food and fibre. It is not. The opportunity to shift our farming systems from a degenerative condition, to sustainable, and via soil heath/soil carbon programs regenerative is the BIG DEAL.… Read more »

This, from the guy who appointed a former Monsatan executive to head the DoA.

You can bet that whatever he does about climate and farming will be targeted to Big Agribiz, not to the smallholder who is actually most capable of truly sequestering carbon.

Why focus so much on agriculture when the transportation sector produces about 3 times the GHG? If we stopped feeding cows grain and using CAFOs we would no doubt reduce GHG.

But you’re missing the fact that one of the largest farmland owners in the country is Bill Gates. Yeah, now you’re getting why there’s a government payout for farming a certain method. Money connections.

Joe Biden, in league with a spendthrift, yet bi-partisan Washington DC may very well bet a figurative farm on their latest fashionable globalist nonsense, but a midwest farmer would be a fool to bet his own real farm for the same. After the reserve currency of the world is debased, the American masses will still need to eat…no matter how they voted or what political ideology they might embrace. They always do. Eventually all currencies created out of fairy dust return to fairy dust. Prime farmland, however, just waits for spring in order to reload for next falls coming bounty…if… Read more »

Just to try to be clear, exactly what is Bidens plan to stop the natural cyclical climate change that our plan has experienced since its formation? Does Biden really expect that his plan of action will actually stop nature’s plan or is it just another political scheme to try to educate the people to stop polluting and clean up the environment? No one elected Biden the worlds czar or the Worlds President, unless you can get all countries, rich and poor alike to recognize the environmental impact of plastics in our food chain isn’t a good idea, that hundreds of… Read more »