A Canadian inventor wants to clean up agriculture's ecological damage by turning manure into drinking water.

Agriculture already consumes 70 percent of the world’s water supplies, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, but the pressure on farmers to become better conservationists has never been greater. Several states have begun regulating water treatment. Seeking provable farm-scale solutions, some CAFO (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation) pork and dairy producers have turned to an invention by an unlikely entrepreneur from an unlikely place.

“There are companies treating manure, but not creating clean drinking water,” says Ross Thurston, a chemist from Canada’s oil and gas hub, Calgary, who spent two decades cleaning contaminated groundwater sites in the energy industry. His company Livestock Water Recycling (LWR) focuses on agriculture, developing and selling technology that pumps hog and cattle manure into solid nutrient byproducts and pristine, pathogen-free water – all of which can be reapplied as fertilizer or for irrigation. “Everything is usable,” he says.

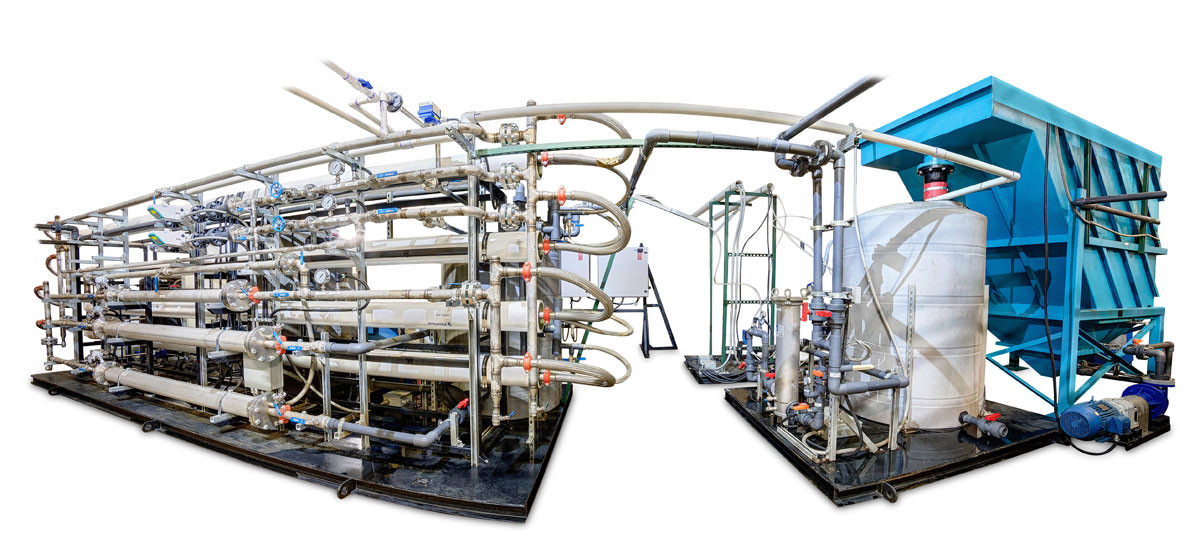

A typical LWR – from the funnel guzzling up to 30 million gallons of effluent a year to the faucet spewing drinkable water – is 60-by-100-foot. It’s essentially a municipal water treatment plant on farm property. But at a cost of $500,000 to $1.5 million, and with dairy and pork prices bottoming out, will farmers buy in?

But at a cost of $500,000 to $1.5 million, and with dairy and pork prices bottoming out, will farmers buy in?

“We’re always looking for things that increase the sustainability of our farms,” says Bill Harke, director of public affairs for Milk Source, a consortium of dairies that’s in the midst of setting up LWR on a Hudson, Michigan, farm with 3,000 cattle. Milk Source operates large dairies throughout the state and Wisconsin, applying sustainable agriculture practices to CAFOs through sand and manure recycling. Harke says the next logical step is recovering water from the effluent – and that’s where LWR comes in.

Milk Source began planning for an LWR in mid-2014. Over the year, they modified a building required to house the technology and began training multiple staff members so that it can be a 24-hour operation. Harke says they’re currently “working through issues that you have with new technology.” He adds, “We’re getting some clean water out now. People on tours have been very fascinated by it.”

Thurston from LWR says about 15 companies across North America have invested in his technology since 2008, five of them just in the last six months. But not all of the installed LWRs stayed in operation.

“The equipment is still sitting there,” says William Kingma of the technology. Kingdom Farms, his 2,300-head hog operation in Bentley, Alberta, was one of the first to invest well over $500,000 in an LWR payment plan, manure pipelines, and a new building to treat 40 gallons of manure per minute. It never got there. Not even close, actually. “We tried it on and off,” he says. “It wasn’t sized for our farm. It would have worked; we just had to double the system. I wouldn’t mind trying to incorporate that technology properly.” Although he lost money on the investment he says it “wasn’t a complete waste” because he understands the water extraction process better.

“Like any industry you need time to get mature technologies that improve the reliability of the product,” says Craig Frear, a former researcher and professor at Washington State University who worked in the Center of Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resources. (He recently took a position directing research and development for Washington state-based anaerobic digester company Regenis.) But price is the biggest frustration for farmers when it comes to technologies like LWR, he says. “The closer you get to clean water, the higher the cost.”

But Thurston doesn’t just promise an environmental solution via LWR; he promises a profitable one to businesses of at least 2,000 or more head of cow or a few thousands pigs. By separating fertilizer nutrients, he says, farms can apply them – proportionately – to their crops, then sell additional byproducts to others. It also reduces the need for lagoons and costly water hauling, which also causes soil compaction. “It lets you expand your farm,” says Thurston. “You can grow.”

This makes Paul Wolfe, a policy specialist at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, nervous. “It creates a vicious cycle of getting larger scale [farms] to make these economies of scale work, and we just get larger and larger factory farms,” he says. “It’s great they’re trying to address this issue, but we need to move beyond the CAFO system to a more integrated one that’s better for the farmers, the land, and the animals themselves.”

There’s no evidence to think the CAFO system will slow. Europe’s recently lifted milk production quotas will only grow dairies. And while climate change exacerbates drought, the UN estimates global food demands will increase 70 percent by 2050. CAFOs will likely play a big role in feeding them – and should do it in their greenest ways possible, says Thurston. “As much as people say that it’s the big operations that are the problem, they’re not, because the big operations can actually do something about it.”