Researchers have found that a few seemingly innocent letters or strings of sentences have incredible potential to shape our views. But can they mold global economic systems? The answer it seems is yes. In her first book, “Global Appetites: American Power and the Literature of Food,” author Allison Carruth examines how literature both shapes and […]

Researchers have found that a few seemingly innocent letters or strings of sentences have incredible potential to shape our views. But can they mold global economic systems? The answer it seems is yes.

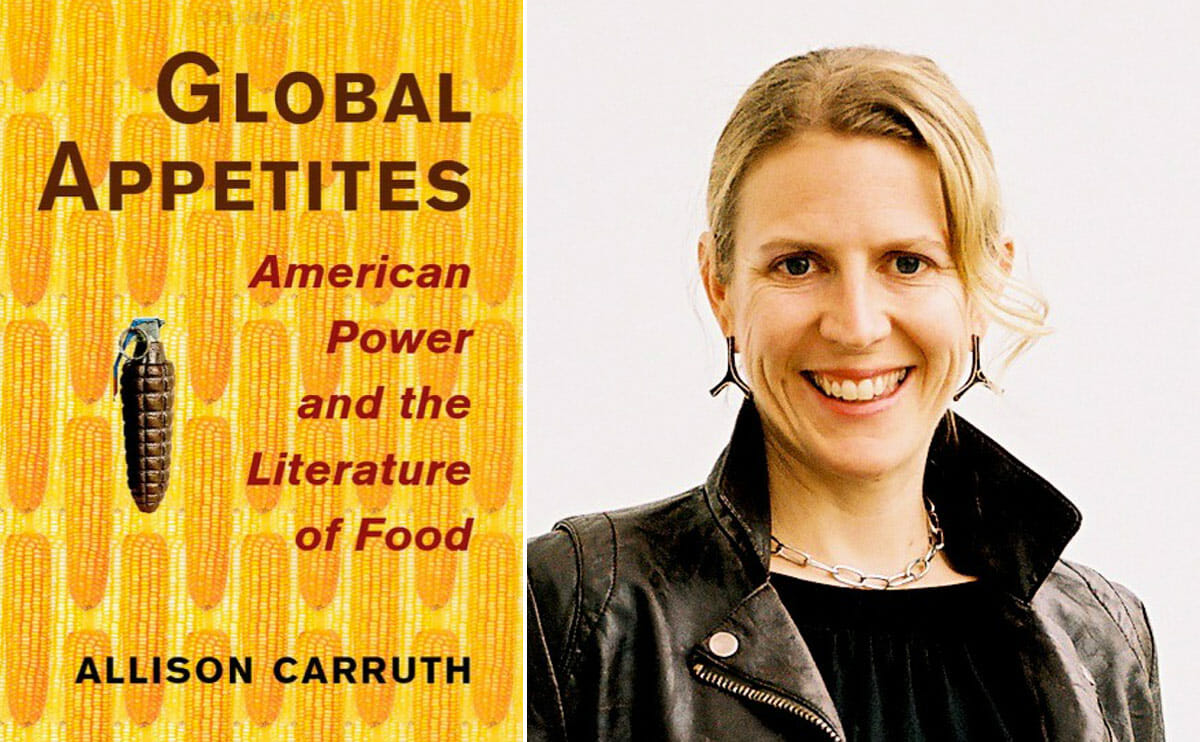

In her first book, “Global Appetites: American Power and the Literature of Food,” author Allison Carruth examines how literature both shapes and exposes movements in the nation’s food systems and policies since the World War I. Now a professor at the University of California Los Angeles, she conducted her first research in the agriculture- and literature-friendly Bay Area; she immersed herself in the area’s sustainable agriculture movement while earning her English Lit. doctorate from Stanford University.

Carruth’s extensive research brought her from magical realism books all the way to today’s top-selling food memoirs. We spoke with Carruth about her work at the intersection of food and literature.

Modern Farmer: When did you realize food was a field that interested you?

Alison Carruth: That’s something that goes back to my childhood. I started cooking on my own when I was 7 or 8 years old. I was just endlessly fascinated by flavors, colors and textures, by the experience of putting together a menu. I would do these elaborate dinners for my family when I was maybe 10 or 11. I would create menus. I had these cookbooks written for children. I even had my own napkin-folding book!

When I moved to the Bay Area, it was such a Wonderland to me. There was enormous talent in terms of chefs, bakers, artisanal food makers, but also so much going on around the politics of food and the history of that going back to the 60s or 70s. San Francisco was where food started to take on intellectual and political importance in my life; before it was mostly a hobby.

MF: In your book, you deal with literature, but that doesn’t just mean fiction, right?

AC: I define literature very broadly to include not just established genres like the novel, lyric poetry and drama, but also cookbooks, food memoirs, restaurant reviews, even advertising. These all tell very provocative stories about our food system – whether they’re commissioned by Monsanto or by Slow Food International.

MF: What is your central argument in “Global Appetites”?

AC: My argument is that we cannot understand a concept like globalization or history of the U.S. rise to becoming superpower without looking closely at changes in how we grow and consume food.

When we talk about globalization, we neglect just how important food and agriculture is. The tendency is to focus on more abstract mechanisms for global power like finance, trade agreements or international borders. No doubt they are crucial, but it was interesting to me that food and agriculture’s role was a minor point in both academic and mainstream discussions.

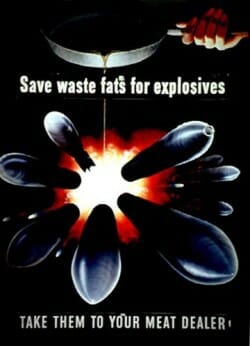

A WWII poster that inspired Carruth.

MF: Can you give us an example of that happening?

AC: Well, after World War I, President Calvin Coolidge gave an incredible speech to a group of farmers and foreign policy people calling agriculture as a “great industrial enterprise.” That was unprecedented. Before then, farming was seen as a retreat from industry.

MF: Do you have some favorite “Aha! moments” while writing this book?

AC: My first Aha moment was seeing this poster of a woman’s manicured hand, holding a skillet with bacon grease dripping down into a cluster of exploding warheads. It became my argument in miniature in visual form.

I went back to the writers of the time and realized that wherever there was a connection between starvation and prosperity, there was also reference to war. Chemical weapons are the same compounds as pesticides. Pesticides become a way of creating economic markets out of war chemicals during peacetime. Barbed wire serves both large-scale ranching and trench warfare.

The list goes on and on. It was a huge moment for me to think about the darker side of agriculture. Although it is productive at least in staple crops, it creates this profound social inequality that many writers saw as a violence equivalent to war.

MF: What do you hope people will take away after reading your book?

AC: For people interested in agriculture movements, I hope they gain a historical depth from reading the book. “Global Appetites” provides a back-story for the politics they’re involved with now.

I also hope it provokes people to interrogate both the strengths and the blind spots of their own politics – to ask questions. What kinds of local connection do we want to encourage between farmers and consumers? What are some of the globalized connections that are valuable, even if we’re deeply committed to environmental sustainability and social justice? What trade-offs and conflicts emerge when we talk about food justice? How can we address these things?

(This interview has been edited and condensed.)