A Win for Growers Who Protect Biodiversity on Agricultural Land

By mapping wildlife and endangered plant species on agricultural land, growers are empowered to make adjustments that don’t impede their productivity.

A Win for Growers Who Protect Biodiversity on Agricultural Land

By mapping wildlife and endangered plant species on agricultural land, growers are empowered to make adjustments that don’t impede their productivity.

Maynard Mallonee looking at State Sensitive Wyethia angustifolia courtesy of Joe Rocchio

Truth be told, cattle farmers are no fans of lupine. If a pregnant cow chows down on the plant, its toxins can cause the unborn calf to be born with crooked cow syndrome and be unable to walk. In most instances, farmers will spray the plant with herbicide and kill it. But on Mallonee Farms, a Washington State dairy farm, things are different. Instead of eradicating the undesired plant, it is protected.

As a host to the larvae of the endangered Fender’s Blue Butterfly, Kincaid’s lupine was declared a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act in 2000. Only found in small areas of prairie grassland west of the Cascade Mountains, Mallonee Farms is the northernmost epicenter for the lupine in the US.

All across North America, endangered plant species and wildlife are struggling to survive on agricultural land. The United Nations Environment Programme has pegged the global food system and its encroachment on wildlife habitats, along with its use of fertilizers, pesticides and other chemicals, as directly threatening 86 percent of species at risk of extinction worldwide. In the United States, more than 50 percent of threatened or endangered species are vital pollinators such as the Fender’s Blue Butterfly. Without pollinators to fertilize berry crops, orchards or field crops such as squash, all of us eaters are also endangered. But, it’s not always easy for growers to identify those species at risk on their properties.

Until its discovery in 2004 by an eagleeyed employee of Washington State’s Department of Natural Resources cycling past one of the farm’s pastures, Maynard Mallonee had no idea the lupine on the family property was endangered.

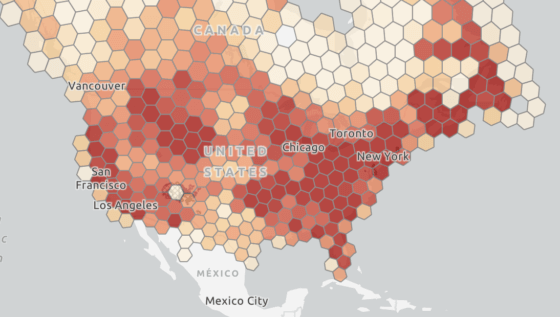

NatureServe is a US-based not-for-profit organization that acts as a clearinghouse for biodiversity data. Through remote sensing such as wildlife cameras, collaring of wildlife, satellite imagery, drones, geographic information systems (GIS) and on-the-ground eyewitness observations, analysts can predict where wildlife and plant species at risk might be on agricultural land.

Compiled into maps, the information is used by government agencies such as state departments of natural heritage, fish and wildlife services, conservation organizations and individuals across North America to tailor responses that support at-risk species. These might include, as in the case of the Mallonee Farm, adopting rotational grazing practices or, in other instances, altering haying schedules. But nothing is full-proof and the surveying of private land is, after all, voluntary.

“We can’t survey everywhere,” says Regan Smyth, vice-president of conservation and science for NatureServe, “which makes a lot of things hard to know.”

She also admits that when it comes time to do on-the-ground surveys to verify the predictive data, growers can get a little ornery about sharing information. They worry about the inconveniences it might cause to production. After the lupine was discovered on the Mallonee family farm, the Department of Fish and Wildlife told Maynard Mallonee to come up with a rotational grazing plan for his cattle that protected the lupine.

“It’s big government telling you what to do,” says Mallonee, “and if you don’t do what they want, they can make life difficult.”

For the most part, Smythe says people managing land care about it and want to do the right thing. “Once people understand working lands need to be part of the picture of how we keep a diversity of life on the planet, then those who might in other circumstances not want people traipsing around their property become collaborators with Natural Heritage programs,” she says.

In Utah, the Wildlands Network uses mapping data to predict the migration corridors of wildlife. Hunter Warren is engagement coordinator for the organization and concurs with Smythe that there can be a mixed reaction from landowners when they learn that a migrating herd of mule deer, for example, will be stomping through their property. But once they learn that any adjustments needed to support the wildlife, such as replacing barbed wire fencing with fencing that won’t snag and harm an animal, will be paid for by the organization, they become more receptive.

Migrating herds of deer or elk, for example, can, through their grazing and trampling of the ground, break down organic matter into the soil, releasing nutrients that benefit crop production. Plants such as Kincaid’s lupine through their root systems create pathways in the soil that allows for enhanced water filtration and carbon sequester.

Bryan Gilvesy is CEO of the Alternative Land Use Services Program (ALUS), a non-profit organization working to help fund grower’s initiatives in six Canadian provinces and in Iowa that protect species at risk. He relates how in Southern Ontario a farmer discovered his hay field was home to 250 bobolinks, a bird assessed as being of special concern in Canada by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and listed under the Species at Risk Act. A ground nesting bird, the bobolink prefers grasslands and prairies to lay its eggs. As more land is converted for agricultural use, the bobolink’s traditional nesting areas have become endangered. Combine or tractor harvesting destroys eggs and can even result in the deaths of birds. ALUS worked with the farmer to alter the haying schedule so that the fledgling bobolinks had time to grow.

“The farmer got a more mature hay crop and was rewarded financially,” says Gilvesy.

A report by The American Farmland Trust has concluded that managed agricultural land can support both food production and wildlife. It advocates for a broader approach to mapping biodiversity on agricultural land and enlisting the help of farmers and ranchers to do it with policies that embrace the USDA’s legacy of voluntary, incentive-based and locally led conservation.

On the Mallonee farm, the latest mapping shows a 33-percent increase in the lupine’s population. And although the farm’s grazing plan is having to be constantly updated and re-filed with the Department of Fish and Wildlife to accommodate the spread, Mallonee is happy he took the time and effort to protect the plant.

“In the beginning, maybe I might not have,” he says. But, without question, Mallonee is happy he did. The benefits of taking action to protect the lupine have been worth it. “The dairy farm is better managed through the rotational grazing methods we’ve developed,” he says.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Jennifer Cole, Modern Farmer

June 6, 2024

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Very cool to see farmers willing to try new methods. Farming is so high risk. I understand the reluctance to be told what to do. But when everyone wins including the natural world, then it’s a net positive.

The books are brief, with about 100 pages apiece that feature exquisite drawings.