How the Hunt for Wild Ginseng Changed America

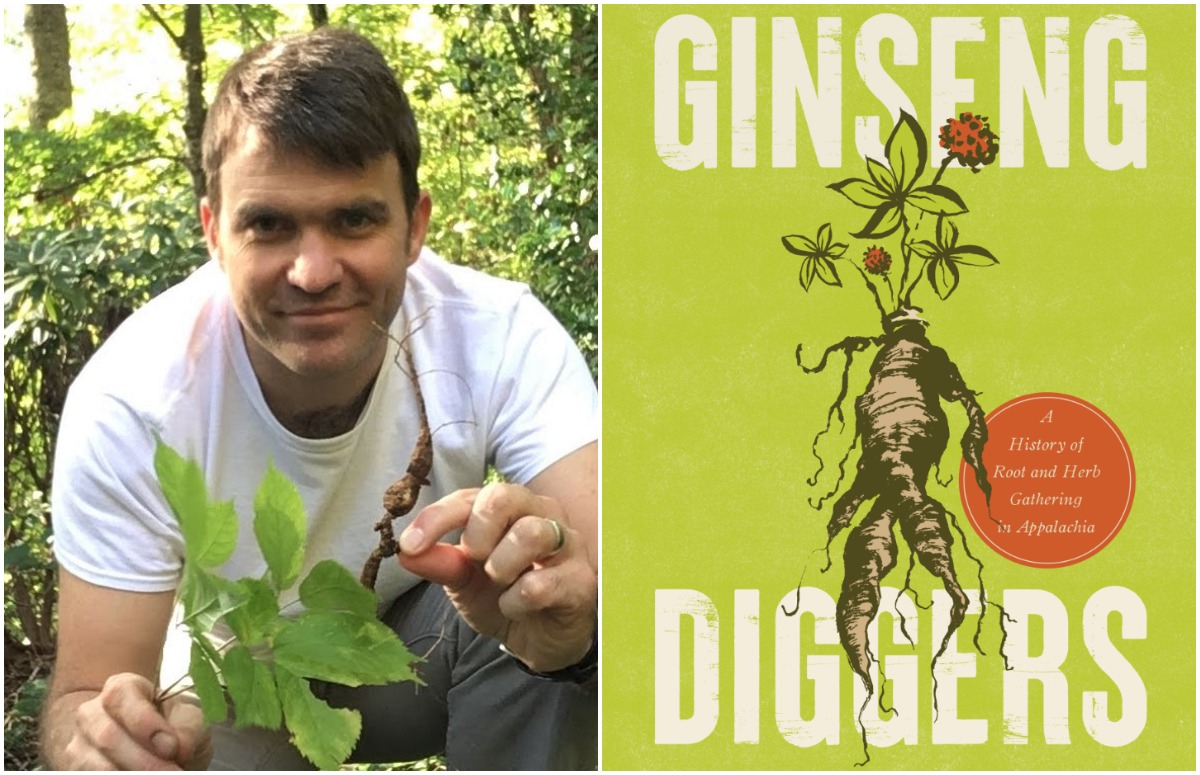

In his new book, Luke Manget shows just how integral ginseng was—and still is—to the Appalachian experience.

How the Hunt for Wild Ginseng Changed America

In his new book, Luke Manget shows just how integral ginseng was—and still is—to the Appalachian experience.

Ginseng root is known for its therapeutic and healing properties,by artin1, Shutterstock.

There was a time, not too long ago, when ginseng studded the forest floor. From Alabama up to the foothills of New York and further west, pointed leaves with jagged edges and small, bead-like red berries popped out of the rugged hillsides. Native Americans used the root as a stimulant and to treat headaches, fever, indigestion and infertility. Wild ginseng was similarly prized throughout Appalachia as an aid for digestion and for giving users a boost of energy. It’s even been promoted as a sexual aid, used to treat erectile dysfunction. And for a time, it became the backbone of the Appalachian economy.

But after decades of over-foraging and mass extraction, wild ginseng is no longer plentiful. These days, going to dig ginseng, or “sang,” is less of a pastime and more of a hunt, with locals hiding their favorite secret spots to preserve what’s left of the plant.

As Luke Manget writes in his new book, Ginseng Diggers, the history of ginseng is not simply a story of plant cultivation or resource management. The history of ginseng in America, and in Appalachian states specifically, is also the story of “the transition to capitalism…the root and herb trade serves as a reminder that the specific impacts of the region’s capitalist incorporation depended on the ecology of a particular commodity’s production.” In other words, the popularity of ginseng pushed Appalachian communities further out of subsistence farming and into wage-earning roles.

It’s a lot to put on a little plant, but Manget did plenty of research, although it was not always as easy as it might seem for such a prominent plant. “You’re looking at sources that nobody’s looked at before,” he says. “You’re piecing together a research landscape that didn’t exist before.”

He looks back to the 1700s, when American ginseng was first found to be purchased in a global market, expanding from there. While Manget pours his research skills into the book (he is a history professor at Dalton State College in Georgia, after all), his first connection to ginseng is a familial one. Growing up in Kentucky, Manget listened at his grandmother’s knee as she talked about digging for wild ginseng. “Being able to put those experiences into a broader context, and realizing that those activities were a significant part of Appalachian history…it helps contextualize my family history a bit more,” Manget says.

Manget’s own family history is similar to many who grew up through much of Appalachia, where ginseng played an important role in the economy. In many ways, it even functioned as a social safety net, sustaining the local community. “If you had a bad harvest, you could always make money [digging ginseng],” Manget explains.

Of course, things have shifted. Ginseng always had local value as a medicinal root. But once American ginseng was introduced to Asian markets in the 1750s, its popularity skyrocketed. Even pioneer Daniel Boone got into the ginseng trade. This prompted intense interest in harvesting wild ginseng, giving way to micro-gold rushes across the region. “Minnesota had a really interesting boom, around 1859. People went there specifically to dig ginseng, and it lasted just a few years before it was pretty much dug out, and declined to the classic boom and bust cycle,” Manget says.

Further south, throughout Kentucky, Virginia and North Carolina, the extraction period for ginseng peaked a little later, when people flocked to the area after the Civil War. Amid widespread economic devastation in the South, people rushed to the hills to find their fortune in ginseng. “The locals who had been used to stewarding patches of ginseng in the woods now couldn’t do that,” says Manget. “They were forced to become more short-sighted and dig up what they could, because they couldn’t rely on it to be there.” North Carolina and Georgia became the first states to try and staunch the mass extraction of ginseng by instituting a ginseng season, with harvesting forbidden outside of the mandated times. Other states soon followed suit, although it’s debatable how effective such mandates were on a larger scale.

According to Manget, it’s difficult to estimate how much money was made from ginseng in a few short decades, but it certainly had an impact on the regional and national economies. In an 1872 report that Manget writes about, Cherokee County in North Carolina produced around 80,000 pounds of ginseng, with each pound selling for about 26 cents, which is about $6 in today’s market, totalling around $480,000 for the season in current dollar amounts. And that was just one county.

It is this fervor for wild ginseng that nearly killed the plant entirely. What was once an abundant root was ripped out of the ground in bushels. Because ginseng has a decade-long growth period, it isn’t easily replaced.

Today, most ginseng is cultivated, with Wisconsin a primary producer of the plant. Although there are still spots where wild ginseng grows, such as Pennsylvania and Tennessee, most diggers are secretive about their hunting grounds. Manget understands the compulsion. While ginseng can be cultivated, it needs a lot of shade, as well as a specific soil density. Cultivation never took off at the same scale, which Manget says is partly because there was a shift in thinking of this free-growing plant as being private property. “People were used to hunting for it, and it was difficult to convince everyone that someone has exclusive rights to it,” Manget says. “That concept was difficult to enforce in some of these mountain communities.”

Plus, many people simply prefer the hunt. Spotting those pops of red berries bursting through the green forest floor is a rush. It’s a sport that never fully died; it’s simply lying low, living on in the Appalachian foothills.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Emily Baron Cadloff, Modern Farmer

March 8, 2022

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Very interesting! Thank you.

Sang pickers learned from this country’s greedy capitalistic ethics that it does not matter if you trespass. What’s important is that you pick it all as soon as you can so some other Sanger, maybe the property owner, won’t get any.

Unfortunately, 95% of our Wild American Ginseng is still exported today. Much of it is still “poached” or illegally harvested. Want to vote your concern about this rare plant that isn’t being properly protected today? Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora is offering a PUBLIC COMMENT until May 21st, 2024… share on how we could possibly protect this plant in a more sustainable way. CITES is a global agreement to ensure that international trade in plants and animals doesn’t threaten their survival in the wild. American Ginseng was at the top of this list… Read more »