Author Shanna Farrell wants more people to care about the agricultural aspects of whiskey, tequila, rum, brandy and other liquors.

Some alcoholic beverages, such as wine and cider, are intrinsically linked to agriculture. When you drive past vineyards, whether it be in California Wine Country or southern New Jersey, you know the fruit being grown will eventually be fermented into wine that’s poured in a winery tasting room. When you visit a local cidery, rows of apple trees are often within view. But that association doesn’t always happen with spirits.

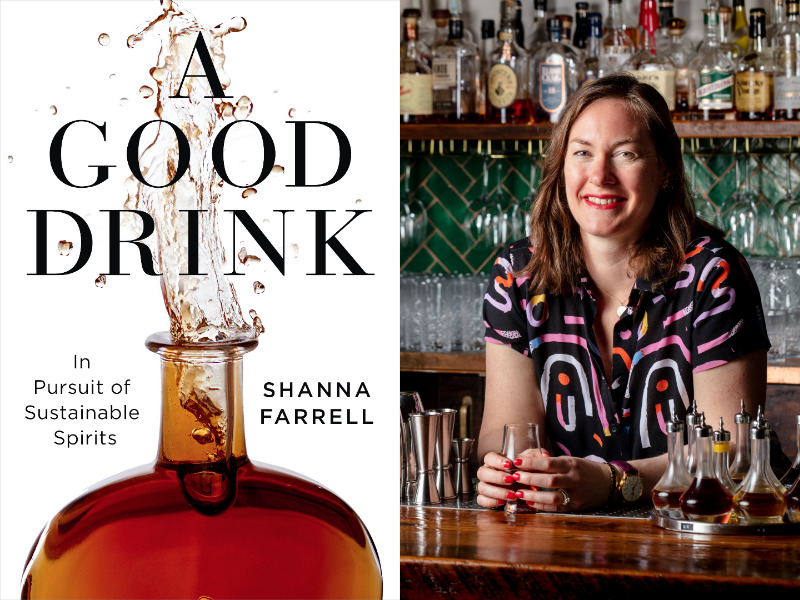

“You can’t visit a distillery and see the crop that’s being grown on site. Only in a very few cases does that exist, so there’s a geographic disconnect,” says Shanna Farrell, author of the new book, A Good Drink: In Pursuit of Sustainable Spirits. “A lot of spirits are made with commodity crops, so a lot of distillers don’t even know where they’re sourcing their ingredients from. They don’t know what state their corn is coming from.”

Of course, all spirits are products of agriculture, too. Before a distiller can transform a crop into something drinkable, a farmer first needs to grow it. Whiskey is produced from corn, rye, barley and/or wheat. Rum starts as sugarcane. Tequila and mezcal are made from agave plants. Brandy requires fruit.

Farrell argues that distillers—and consumers—should care more about the agricultural practices those farmers use. “Just as we need biodiversity in wild plants, we also need it in cultivated crops,” she writes in the book’s introduction. “Among other benefits, genetic diversity in the foods we eat and the drinks we sip protects us against crop diseases, improves soil health, and creates resilience to climate change.”

Although some alcoholic beverage producers have grown more mindful of issues relating to sustainability in their vineyards, orchards, fields and production facilities in recent years—implementing regenerative agriculture practices and embracing hybrid grapes—many have yet to catch up, including a large swath of distilleries and liquor brands.

One notable example Farrell cites is Campari, the bitter Italian aperitif that’s known for its bright red color and viscosity. It’s become synonymous with a Negroni, the three-part cocktail that calls for equal parts of gin, sweet vermouth and a bitter spirit (often Campari). Years ago, Campari used cochineal bugs, which exude the natural dye carmine, to color the liqueur. But that changed in 2006, when Campari switched to using red dye no. 40, the artificial coloring agent that has been linked to cancer, allergic reactions and other ailments. While many people eschew foods colored with red dye no. 40, Campari remains one of the world’s best-selling spirits.

Why do we treat alcohol differently than we treat food? The answers to that question drive Farrell’s narrative quest in the book. Part of the explanation lies in the fact that alcohol is regulated by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), while food products are regulated by the FDA and USDA. That’s why ingredient labels on liquor bottles aren’t required, for example. But other reasons are more cultural, not as easy to identify or change.

Photos courtesy of Island Press.

Farrell’s interest in sustainable spirits was first piqued when she was working as a bartender in her 20s while living in Brooklyn and attending graduate school. “I had spent so much time staring at bottles on the back bar and never seeing anything about ingredients or how things were made,” says Farrell, who began questioning why the farm-to-table culinary movement wasn’t also translating to the drinks she was making for patrons. “I was seeing all these menus that have purveyors listed, where the lettuce is sourced from, how the meat is raised, and what farms they come from. But there was not any sort of attention being paid to how spirits or liqueurs were being sourced.”

As an interviewer at UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center, Farrell knows how to tell a good story and A Good Drink is riddled with them. Traversing the world of spirits, she travels to South Carolina, where Ann Marshall and Scott Blackwell of High Wire Distilling Co. make bourbon whiskey from Jimmy Red corn, a heritage variety of corn that was rescued from near extinction. The couple convinced a few local farms to grow Jimmy Red corn instead of yellow dent corn, a commodity crop that’s easy to grow but often riddled with pesticides and therefore harmful to the soil and environment.

Farrell also goes to Mexico, where tequila producers have endured agave shortages that followed the Mexican government’s 1949 decision that mandated tequila be made from only 100-percent blue Weber agave, despite there being 150 different varieties of agave that grow in the country. She visits small mezcal producers, who are working to preserve traditional ways of making the spirit that are good for the health of both the local people and land.

Back in the US, Farrell visits St. George Spirits in the Bay Area, a craft distillery that originally launched with the goal of distilling local fruit. But when the grower from whom they bought pears, located only miles from the distillery, ripped out his trees to plant more profitable crops, they were forced to find fruit elsewhere. With drought and wildfires an increasing threat in California, St. George has now turned to Colorado to source pears for its pear brandy, introducing a greater carbon footprint to what was once a hyperlocal spirit.

The book ends where Farrell’s journey began: the bar. She highlights a small group of bartenders leading the way, bartenders who carefully source spirits and share the stories of the people who make them. The hope, of course, is that this sort of change will lead not only to a good drink but a better drink.