Name That Orange! The Modern Farmer Guide to Orange Varieties

Valencia! Clementines! Heirlooms? There are so many orange varieties to try. Here’s a guide to some of the more common options.

Name That Orange! The Modern Farmer Guide to Orange Varieties

Valencia! Clementines! Heirlooms? There are so many orange varieties to try. Here’s a guide to some of the more common options.

For much of the U.S., the phrase “winter crops” brings to mind only a few options: daikon radishes, Jerusalem artichokes, turnips, maybe some of the hardier brassicas, like cabbage or broccoli.

But elsewhere, especially in South Florida and California, winter is a joyful time, because citrus is back in season. This year has been a difficult one for citrus growers. Hurricane Irma, in Florida, is estimated to have reduced the citrus crop by about 21 percent, which would make this the worst season for Florida citrus in decades. In California, a slightly light crop is expected as well, which means citrus may be priced a bit higher than usual this year. But, look, so few things bring us joy in the middle of winter; we’ll ready to pay a bit more for a bite of sunshine.

With all that noted, you might be confused by the dozens of different oranges varieties – not citrus as a whole, just oranges – that pop up this time of year. And while the orange may have a reputation as one of the U.S.’s most common and basic fruits (right up there with the apple and banana), it’s actually very special! The orange as we know it is a hybrid of two other citrus trees: the pomelo (which is like a slightly less bitter grapefruit) and the mandarin (which is flat, small, sweet, and orange in color) – it’s not believed to have ever existed in the wild.

(Important! Despite being commonly called the “mandarin orange,” the mandarin is not an orange. The mandarin is one of the two parents of the orange, but to be classified as an orange, a citrus fruit must include a mandarin and a pomelo as parents. That disqualifies tangerines (which are a type of mandarin, probably) and satsumas.)

Oranges were likely first cultivated in southern China (references to the fruit can be found in region’s literature as far back as 314 BC). They’ve since been hybridized, re-hybridized, and altered so much that there are hundreds of orange varieties throughout the world. This is a guide simply to the most common orange varieties, but trust us, that’s complicated enough.

Valencia Orange

Oddly enough, the valencia orange is not from the city in Spain, but was created in southern California sometime in the mid-19th century. Though it is among the most common oranges in the U.S., it’s also the only major variety to be harvested in the summer; the season runs from March to July. Very sweet, with low acidity and a bright orange color, the valencia is the most common juicing orange, though it’s also eaten.

Navel Orange

It’s not totally clear where the navel orange is from – some say Brazil, some say Portugal – but it’s the most popular orange for eating in the U.S. The navel orange gets its name from the fact that it tries to grow a second orange at its base, which produces an effect somewhat like a human bellybutton. They are often seedless and thus sterile; new navel trees come from cuttings rather than plantings. In flavor, a navel is a bit more bitter than a valencia, but also hardier, with a thicker peel.

Clementine

Aha! The adorable little nephew of the orange family. The clementine, named after a French missionary who supposedly discovered the variety in Algeria, is actually a hybrid of a sweet orange (something like a valencia or navel, though we don’t know exactly which one) and the mandarin. Clementines are very tiny, very sweet, seedless, and have a fantastically loose skin and minimal pith, making them easy to peel (no tools required, besides maybe a sharp fingernail to get started), and ideal for eating.

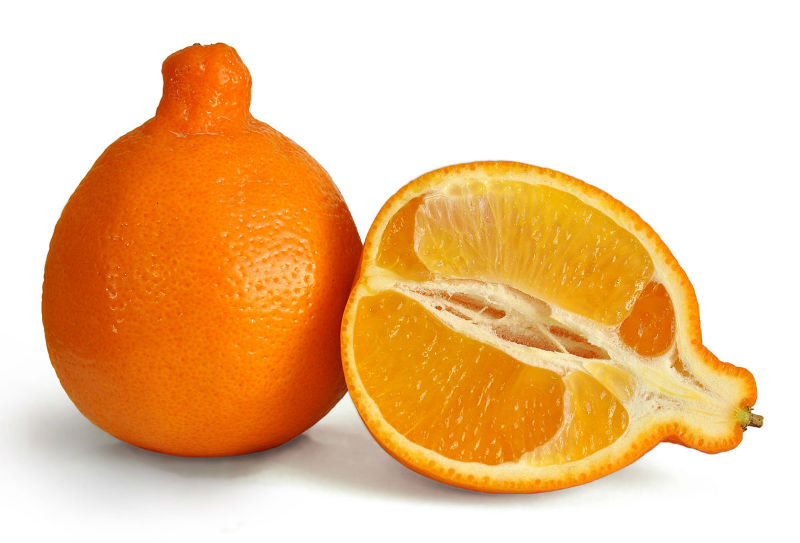

Tangelo

This is a controversial one, but hear me out. The tangelo is, as its name suggests, a hybrid of the tangerine and the pomelo. And the tangerine is (probably) a type of mandarin. (Or a fruit similar to a mandarin. Nobody really knows, but it’s in the mandarin orbit.) The definition of an “orange” is a hybrid of mandarin and pomelo, so, well, okay, this counts. (And to take it even further, the minneola tangelo is a cross between a tangerine and a grapefruit, but since the grapefruit is a descendent of the pomelo, it still counts.)

The tangelo is most easily identified by its reddish skin and the protruding nipple-like thing on the stem end. It’s extremely juicy and sweet, with a very low amount of acid, which makes it an excellent juicing fruit, but the skin is very tight and hard to peel, which makes it trickier to eat raw.

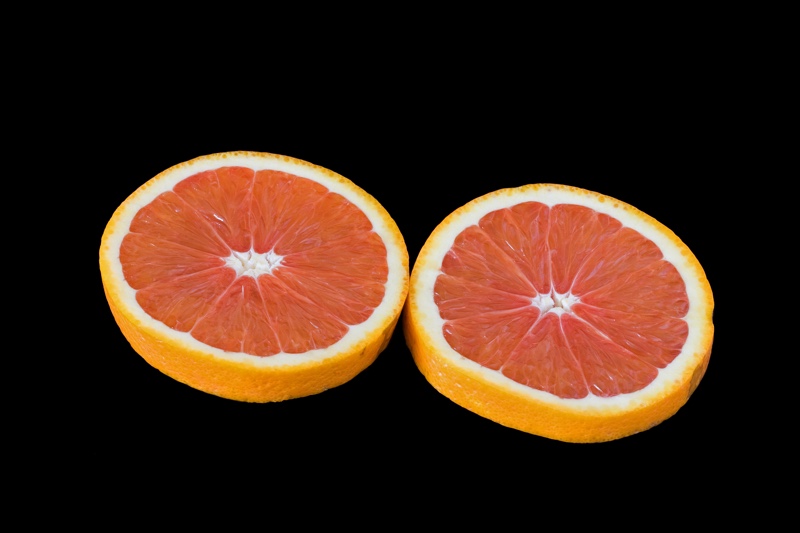

Cara Cara Orange

The prettiest of all oranges is the cara cara. It’s a type of navel orange – it’s sometimes labeled “pink navel” or “red navel” – and was discovered in Venezuela in 1976. It is an all-time great orange, extremely sweet but with a complex sort of berry flavor behind it. And best of all is the color: a luscious pink.

Blood Orange

The blood orange is probably a natural mutation of the regular orange; it has a deep, sinister red flesh which indicates a high level of antioxidants known as anthocyanins. (Most oranges do not have these.) There are a few different types of blood oranges, the most common of which are the moro and sanguinello. Sometimes you’ll be able to see dark blotches on the skin that indicate the deep red within, sometimes not. Blood oranges are not as sweet as the cara cara, but they do have an appealing sort of raspberry flavor to them. Also, their juice is very pretty.

Bitter Orange

An entirely different lineage, but also derived from a hybrid of the pomelo and the mandarin, the bitter orange is sometimes known as a Seville orange or sour orange. Because it’s completely lacking in sweetness, it’s not generally eaten or juiced for standalone drinking. Bitter orange’s peel is extraordinarily fragrant and is often used as a flavoring or spice in its own right; in the UK, it’s common to see it in marmalade. In Europe, this orange is often used to flavor beers, like the Belgian witbier, or as a dessert spice along with clove and cinnamon. The juice is used as a flavoring or marinating ingredient throughout Latin America, especially with pork, as in the Mexican cochinita pibil.

Bergamot Orange

What? This is an orange? Sure is. The bergamot orange, an extract of which is used in Earl Grey tea, is actually a hybrid of the lemon and the bitter orange. It’s usually lime-green or yellowish in color, sometimes smooth and sometimes sort of lumpy, and as with the bitter orange, it’s chock full of seeds. The juice is very, very sour.

Lima Orange

One of the more common examples of what’s called an “acidless orange,” the lima is grown extensively in Brazil. It does not, of course, completely lack acid, but the levels are very low, making this one of the sweeter oranges out there. The flesh is fairly light in color, and it has a thick peel along with some seeds.

Heirloom Navel Orange

So, this is a weird one. When you hear “heirloom navel,” you’d expect an old variety of the navel orange, perhaps long forgotten. That isn’t really the case; a New York Times article showed that, mostly, heirloom navels are Washington navels, the same variety as other ordinary navels. Because there isn’t really a rule about what is qualifies an orange as “heirloom,” the label isn’t necessarily reliable. But some growers take the name seriously, only using rootstock from sour orange trees, the same way they were grown in the early years of California citrus. This produces a lower yield than using a sweet orange rootstock, but the flavor can be superior. Heirloom navels, at their best, are superbly flavorful; not really different in profile from a regular navel, but with higher sweetness and acidity levels.

SaveSave

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Dan Nosowitz, Modern Farmer

February 9, 2018

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

The “Bergamot orange” pictured above is actually a Kaffir or Makrut lime that is used mostly for its leaves in Thai cooking. Bergamot is actually a nondescript looking greenish-yellow smooth-skinned fruit about the size of a common bitter orange. Unfortunately, stock photography sites like Shutterstock are full of these mislabeled images.

Superficial. I was looking for more info on the many varieties of navels.

In the 1940s -50s my great grandmother made marmalade from a very thin skinned tart orange. She sliced them paper thin with a sharp knife, added sugar and cooked up a delicacy. Is that orange available to the public now and what is it?

None of these oranges are what my tree bears. These are very very small with big seeds and thin peel but almost no pith. Most are the size of an olive with some as big as a walnut.

What is it called? It does make a very good marmalade.

Whatever became of Temple oranges? They used to appear in NE grocery stores in Feb but have not been around in recent years.

Is there a variety called Havlin orange

Are Lima Oranges available to grow in the US? My husband is from Brazil, and his mom only bought Lima oranges because of their low acid. I would love to grow one alongside my other citrus.

What the foto describes “tangelo”, I see it as the beloved ” honeybell”. It is only available for a few wks in Fl Jan and early Feb.

I am looking for information about Tupelo oranges.

Anyone know what a ‘Navacot” or “Navecot” is? I’ve been buying them this year; they are slightly flattened, sweet ,but with a good flavour balance, and peel well.