Tyson and Other Meat Companies Linked to Biggest-Ever Dead Zone in the Gulf

Can putting pressure on the meat industry be the best way to impact the entire agricultural system?

Tyson and Other Meat Companies Linked to Biggest-Ever Dead Zone in the Gulf

Can putting pressure on the meat industry be the best way to impact the entire agricultural system?

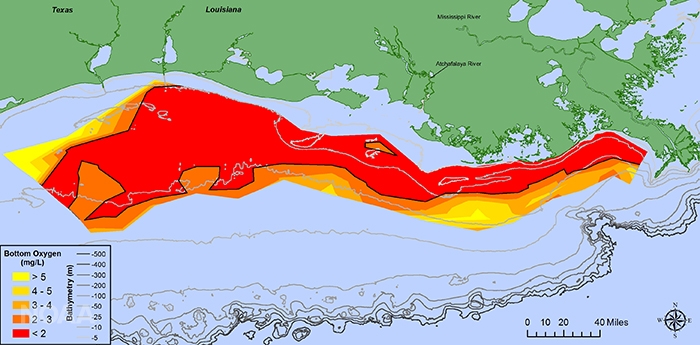

Every year, around mid-summer, a “dead zone” appears in the Gulf of Mexico, just south of the Mississippi River Delta. It is, as its name suggests, a vast swath of highly polluted ocean in which oxygen levels are so low that fish cannot survive. It’s attributed to runoff from the Mississippi River, particularly pollution from the big corn, soy, and wheat-growing states located northward along the river. NOAA has been mapping this dead zone since 1985, and announced this week that this year’s is the largest ever measured – a patch of ocean about the size of New Jersey.

Shortly before NOAA’s announcement, a non-governmental organization called Mighty Earth published its own findings on the dead zone and its causes. (Mighty Earth, a division of the primarily demilitarization-focused think tank Center for International Policy, campaigns for environmental and agricultural causes around the world.) Mighty Earth’s findings go a step further, meting out blame to specific companies: meat producers Tyson Foods and Smithfield Foods, among others.

“America is one of the largest agricultural producers, and one of the largest meat producers, and our number one crops are corn and soy, the majority of which goes to feed the meat industry,” says Lucia von Reusner, the campaign’s director. “We decided to find out who is responsible for driving these supply chains and impacts across the country. And in the same vein, who has the leverage and the responsibility to shift those supply chains to more sustainable practices.”

Mighty Earth believes that the best path to reducing contamination is via public pressure on the point in the meat supply chain most able to effect change.

Von Reusner’s point depends on examining the meat industry’s overall supply chain in the U.S., which works mostly like this: primarily independent corn and soy farmers sell to farmers who raise livestock, many of which are technically independent, but exclusively supply one big company, like Tyson or Smithfield, which in turn often supplies both the birds and the feed to said farmers. That big company then buys animals for processing and sale. “It’s important for us to point out the supply chain, and say, hey, we’re not involved in the crop production business, and frankly, we own very few farms,” says Gary Mickelson, Tyson’s senior director of public relations, on a phone call.

But Mighty Earth isn’t saying that the major meat companies are directly responsible for pollution; instead, they’re saying that these companies are the fulcrum in the entire system – the only entity with enough sway to truly change the way the whole system works. If Tyson or Smithfield decrees that they’ll only buy animals that are fed with a soil-healthy diet, everything changes. The farmers toward the bottom of the supply chain don’t have as much agency; large changes to the way they grow or raise animals could be more expensive and cut into their profits, and those farmers might not have a market for, say, rye or some other crop used to replenish the soil. The farmers can’t really change how they farm, but, says Mighty Earth, the top-level buyer – the meat companies – have the ability to make those changes.

Mickelson says that Tyson buys mostly from grain suppliers who themselves get their grain from individual farmers. “We do not currently have a system to identify a particular row crop from a specific farmer or have the ability to know their farming practices,” wrote Mickelson in a follow-up email. But what Mighty Earth is saying is that Tyson should have a system of policies to encourage better farming practices, that the individual grain farmers are only growing what they know they can sell. If Tyson were to make it clear that they prefer better practices, Mighty Earth believes the farmers would follow.

The research, using publicly available data from NOAA, the USDA, and the US Geologic Survey, compared locations of facilities owned by various companies with data concerning nitrate pollution levels. Tyson and Smithfield ran the highest number of facilities in the parts of the country with the highest levels of nitrate contamination.

If Tyson can figure out how to market organic meat, doing the right thing for the planet might also be doing the right thing for the stockholders.

If you’re thinking that sounds like correlation and not causation, well, yes, sort of. Mighty Earth didn’t factor in the size of the individual plants, meaning that a very small facility and a very large facility, though not equal in terms of pollution output, would show up as equally responsible on their map. And the size of the facility could reflect the amount of grain these companies buy from a given area. Tyson, for example, writes that they “buy local grain, which is used to raise our poultry, feed your community and feed the world,” on its website. Bigger facilities could then equal substantially more local grain, and when that grain isn’t grown with the environment in mind, could equal more pollution.

That said, the US meat market buys 40 percent of American corn (another 40 percent goes to ethanol) and 70 percent of American soybeans, and Tyson controls a whopping 25 percent of the entire meat market (that’s chicken, beef, and pork). Tyson is also the only company to have facilities in all the states NOAA says contribute the most to the Gulf’s dead zone.

In any case, Mighty Earth is very intentionally naming these companies; they believe that the best path to reducing contamination – as well as a whole host of other benefits, environmental and economic – is via public pressure on the point in the meat supply chain most able to effect change. “The meat industry is the dominant shaping force of how agriculture is produced in the United States,” says von Reusner. Farmers are not really in much of a position to change anything; they farm what can sell, and their buyers are meat producers who demand corn and soy. That narrow-focused demand creates many of the problems in agriculture, the most pressing of which is that monocropping depletes the soil of nutrients, forcing the use of more fertilizer, the excess of which runs into rivers and streams. “Tyson and other meat companies are really in the best position to shift the market, shift practices, shift incentives for agriculture across America,” she says.

The upsides are strong for this case; aside from the fact that increasing incentives for crop rotation and responsible fertilizer and soil use is, it’s fair to say, the morally correct thing to do, there’s also money to be made here. Consumers are increasingly looking for, and sometimes willing to pay more for, sustainably produced food; organic food profits have outstripped conventional food profits by a mile over the past decade. If Tyson can figure out how to market it – and hopefully if the USDA can figure out how to regulate the claims – doing the right thing for the planet might also be doing the right thing for the stockholders.

“As part of our deepened commitment to holistic sustainable food production, we’ve begun the process of evaluating all the parts of our supply chain where we believe we can make positive impacts, so we may one day seek to partner with crop farmers on their practices,” wrote Mickelson in an email. But in our phone conversation, Mickelson seemed to feel Tyson was being unfairly blamed for the problem. “People think we’re a bad actor based on what some small environmental group came up with and how they decided to pin it on Tyson because we’re a well-known brand,” he said.

Beginning an evaluation process, and including a phrase like “we may one day seek to,” may not be particularly comforting to activists who think Tyson and other meat companies are in a position to make large-scale changes to a disturbing environmental problem. But work like this does achieve its initial goal of putting companies on their heels. Tyson was forced to respond, and that’s a small step forward.

Updated 08/08/2017 with additional comments from Tyson.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Dan Nosowitz, Modern Farmer

August 3, 2017

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.