Meet the Women Making Waves in Maine’s Tough Lobster Industry

Lobstering, a field traditionally dominated by men, is physically and emotionally demanding. For a growing number of women, that’s part of the draw.

Our waterways can feel unknowable.

But just like in other areas of our food supply, there are people working to improve water conditions and ensure sustainable aquaculture practices are in place for generations to come. This collection of stories from our archives highlight just a few of these efforts. From fighting ocean plastics with fungi to bringing sub-sea foraging to the dining room, these people are working to make our waters a better place. And many of them are bucking longstanding traditions, like the women who have found their place in Maine’s lobstering communities, or the folks making oysters accessible to everyone.

The oceans, lakes, and rivers around us may be vast and strong. But these stories, and others in our archives, show that we can be strong as well, when we work together.

In this series

Meet the Women Making Waves in Maine’s Tough Lobster Industry

Lobstering, a field traditionally dominated by men, is physically and emotionally demanding. For a growing number of women, that’s part of the draw.

The Oyster Farmers Working to Address Aquaculture’s Big Plastics Problem

Innovative producers and researchers are turning to wood, cork, mushrooms, and other materials in an effort to reduce the use of plastics in our waterways.

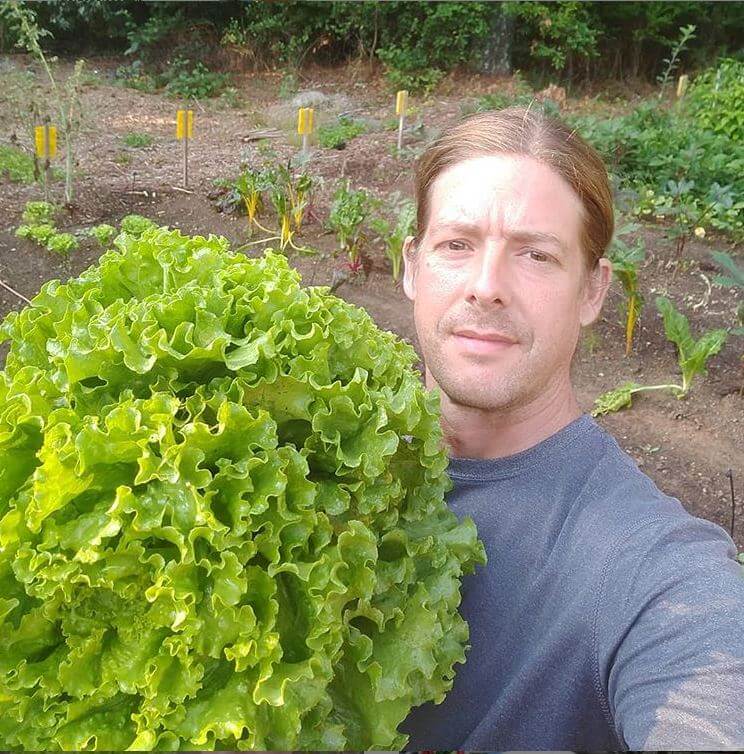

Meet the Modern Trout Farmer Using Gravity to His Advantage

Ty Walker wants to bring old-school, sustainable trout farming back to Virginia—and he’s succeeding.

How One Chef is Embracing Seasonal Food with Sub-Sea Foraging

In Newfoundland, where the ocean is at your doorstep, seasonal food goes far beyond what’s growing in the garden.

Meet The Modern Farmers Creating Public Oyster Gardens

South Fork Sea Farmers helps families grow their own oysters and see the importance of sustainable marine aquaculture up close.

Meet the Mycologist Stopping Ocean Plastics, One Mushroom Buoy at a Time

A surprisingly buoyant material, mycelium can help aquafarmers and fishermen end their dependency on plastic gear.

Just a Few Acres Farm in Lansing, NY has nearly 500,000 subscribers on YouTube, where seventh-generation farmer Pete Larson posts videos with titles like “The basics of cutting hay” and “Playing in the Dirt with Pregnant Pigs”. The videos cover everything from dealing with his cattle and daily chores to advice for aspiring small farmers hoping to avoid burnout—many of whom leave comments thanking Larson for the tips.

The tips are especially helpful for folks hoping to make a go of farming on smaller plots of land. Given the challenges in an industry dominated by factory farms, such as slim profit margins and little control over pricing and markets, between 52 percent and 79 percent of small family farms are at high financial risk. More than half of small farmers also have to work a second job to make ends meet.

“We only have 45 acres, which is a really small farm around here,” says Larson. “Conventional wisdom was [that] you could never make a living off that small amount of land, because the farmers around here are all commodity farmers.”

But, some small-scale farmers like Larson have been able to make their operations profitable with creative techniques such as monetizing their social media presence and carving out interesting, competitive niches.

READ MORE

Have questions about how to transition away from factory farming? We have answers!

One way Larson did this is by finding breeds with great marketing stories behind them, such as Dexter cattle. Brought back from near extinction by homesteaders who wanted a dual purpose for beef and dairy, this Irish heritage breed works well for Larson because of their smaller size and good beef quality when raised on grass without grain.

“You want to be able to tell a story to customers that they can buy into,” says Larson about his choice cattle breeds. “You need to have a marketing hat on as much as anything else.”

Eventually, says Larson, the farm began to make enough money for the family to take home a profit. Then, about seven years into the endeavor, Larson says he had another idea: monetizing Just A Few Acres’ social media to help support their small livestock farm.

“It’s enabled us to … gradually, taper down the numbers of animals that we raise,” says Larson. “And it’s allowed me to say, ‘well, if I’d like to retire before I die, I can do that now.’ It’s given us breathing room.”

Likewise, across the country, Rob Miller and Melanie Jones had to think way outside the box—and their own fence—in order to acquire enough land to farm in Woodstock, GA. As owners and operators of Trefoil Gardens, they adapted a “multi-locational” model that has grown into a neighborhood agricultural cooperative, and it relies on the partnership of their neighbors.

Through a program called SPIN-Farming, which stands for small plot intensive and teaches aspiring farmers to take a systematic approach to backyard-scale growing, Miller says he was able to connect with a farmer who already had a template for a yard-sharing contract. He brought the contract over to his neighbor, and they broke ground on their first neighboring plot on July 4, 2016.

Now, with plots spread across the yards of six of their neighbors, and a few others a two-minute drive from their suburban home, they currently have 15,000 square feet under cultivation. Since then, Trefoil has been able to take its yard and neighborhood to new levels of productivity. The SPIN program has also helped thousands of other farmers use this multi-locational approach to farming on limited space.

But, Miller says it took him a long time to stop burning himself out with the hard work, and to get to a sustainable mindset.

“We’re a mission-driven company, and I know a lot of a lot of people in our space are and so, for us, it’s not so much about money, but at the same time, we’ve got to earn a living. This thing has to be financially sustainable,” says Miller. “It’s been a big transition to move from that solely mission-based focus… you can only do that for so long before you just burn yourself out.”

Given the yard-sized scale of the operation, they have had to really look at which crops have outsized value for profitability, and which are too time-consuming or fickle to rely on in such a limited space. Miller says Trefoil has recently pivoted toward perennial instead of annual crops because they are more manageable and save time.

“We’ve also really dialed in to floral and mushrooms, and then also herbal products, botanical products,” says Miller. “It’s a joke, but it’s not really, that we grow food so that we can get into our farmers markets, and then we grow flowers so that we can afford to grow the food that we bring to the farmers market.”

LEARN MORE

What is a conservation easement?

Trefoil has also had to look at non-traditional methods of selling, because growing on spec with such little land became not only impossible but also incredibly stressful. So, Trefoil took on a community-supported agriculture (CSA) food box subscription model with a short subscription period allowing them to pivot based on what was growing well.

Now, having been profitable for the last three years and selling 25 food boxes at the peak of this year, they’ve also found creative ways to cut costs as compared to a traditional agricultural plot of land.

“We’re in an older neighborhood and so everybody’s on septic systems, so there’s no sewer,” says Miller. “The water is pretty inexpensive for our neighborhood, and that’s really important.”

For many things, though, Miller says they rely on their relationships and community. “I wake up every morning fully indebted to everyone around me, and it’s the most freeing thing in the world. And it just sounds counterintuitive, but it’s true,” he says.

While Larson has also been successful by building up his community, albeit online, he cautions against expecting the farm to be profitable from the start, and he encourages aspiring small farmers to have some kind of a safety net, be it savings or part-time work off the farm.

“You have to have some kind of financial security to start out, because … you don’t have any income from the farm on day one,” says Lason, explaining that he and his wife had some savings that they lived off in a “very modest way” for a few years.

“When we sold our first products at market, everything that came back, the money that came back in stayed on the farm side, and we used that to reinvest and gradually, bootstrap ourselves and grow the size of the farm,” says Larson. Despite land becoming increasingly expensive for aspiring small farmers, a little creativity can still make the business viable.

Michelle Scott, the communications and development manager for the Wood Buffalo Food Bank, recalls the lightbulb moment that cemented the importance of having culturally relevant food available for their clients. A gentleman from North Africa was given a generic food hamper and he had to ask what the dried bag of pasta was, and what to do with it. “How unfair is it for us,” says Scott, “to say we are doing things to feed everyone in the community but yet people we are feeding don’t know what they are eating.”

The Wood Buffalo Food Bank, in Fort McMurray, Alberta, fed 15,000 clients in 2021/22. According to Scott, the region is a hub for newcomers to Canada, and she estimates that at least half of the food bank’s clients are unfamiliar with Western food.

Scott’s realization underscores a significant challenge faced by food banks and pantries across North America: Food is more than just fuel for the body. It carries deep significance that connects individuals to their beliefs and heritage. Food banks, though, are non-profit entities and, like the rest of us, are challenged by the high cost of food. This often means that they buy calorie-rich inexpensive products: canned soups, tinned fish, or dried pasta. But, these foods are not always the only foods people want.

TAKE ACTION

Donate to a food bank through Feeding America.

Feedback received by the the Ottawa Food Bank from a pilot project conducted between 2019 and 2020 indicated a desire for ethnocultural vegetables, such as okra, a traditional staple in African diets, to be available at food banks. Now, the food bank grows okra on its farm.

Similar data was revealed in a report by the Food Bank of the Rockies, which found that individuals visiting food pantries that don’t offer cultural food preferences often feel stigmatized, unwelcome and unwilling to return.

Recognizing the importance of culturally relevant food, Dan Edwards, executive director of the Wood Buffalo Food Bank, shared how it has always tried to incorporate specific items into its hampers. “We’ve made sure to add supplies for Bannock, a traditional Indigenous food, when it’s within our budget and capacity,” says Edwards. Items such as corn flour, Halal meat, lentils and spices are now added to food hampers if requested.

In Newton, Massachusetts, the Newton Food Pantry (NFP) started offering culturally relevant foods during the early days of the pandemic. “We offered things like celery, garlic, ginger, tofu, and Russian cheese,” says Sindy Wayne, board president of the food bank.

Flash forward to 2024: Client registration forms and intake reflect a significant percentage of food pantry clients as Russian/Ukrainian, Chinese (Mandarin/Cantonese speaking), and Hispanic/Latino (Spanish speaking). Each month, the NFP receives funding from corporate sponsors for 100 percent of the purchase of ethnically appropriate food.

“Our hope is that, by offering culturally relevant food, our clients know that we see them beyond their need for food,” says Denise Daniels, pantry manager at the Newton Food Pantry. “In their time of need, we hope they will create familiarity and a sense of home through their meals.” Part of why clients return to the food bank is that it supplies food items with which they are familiar and like.

One of those returning clients, Daniels recalls, was a woman from Guatemala who noticed that the pantry was stocking a cassava-based cracker. Excited to find an item she was familiar with from her home country, she has returned multiple times to the pantry. The pantry also stocks buckwheat flour and eggplant spread for recently immigrated Russian/Ukrainian clients.

Feeding America reports that of the 47 million people in 2023 who experienced food insecurity, 14 million self-identified as Latino, and more than nine million Black Americans could not access enough food to lead healthy active lives. In Canada, Statistics Canada reports that 28.6 percent of Canada’s Indigenous population 15 years old and older (excluding those living on reserve and in Canada’s three northern territories) experienced food insecurity at some point in 2022.

“There are so many different cultures throughout the United States,” says Molly Kern, chief executive officer of the SLO Food Bank in San Luis Obispo County, California. “What mattered most to us was listening to our community and understanding what their needs were.” Staff at the food bank spoke with nearly 350 community members, finding out what challenges they had accessing food, and, most importantly, what role food plays in their lives. The feedback they received was incorporated into the food bank’s 2023-2028 strategic plan.

LEARN MORE

Learn more about the importance of culturally relevant food.

“Regardless of cultural background, a big trend was looking for fresh fruits and vegetables,” says Kern. In San Luis Obispo county, the population is slightly over 280,000. Between 2010 and 2022, the Hispanic/Latino community grew 3.3 percent to become almost a quarter of the area’s overall population at 24.1 percent. Dried beans, fresh chilis, onions, and tomatillos, as well as fresh tortillas, are items familiar to Latino traditions and rank high on the list of foods that are available on food pantry shelves.

“We measure satisfaction by how fast things fly off our shelves,” says Kern. “And when people know you are listening to them and caring for them, and working to improve,it builds trust.”

At Modern Farmer, we believe that food is a right. More specifically, access to nutritious, locally-grown food, is a right.

Unfortunately, not everyone has access (or enough access) to food.

But our food systems don’t have to look they way they currently do. We don’t have to accept the status quo. We can rise, as a community, and demand equal access to food. We can push for the right to grow food, and support our local food producers. And change can happen, from the smallest community garden to city and county-wide initiatives.

With that in mind, here are a selection of popular stories from our archive which highlight the ways cities across North America as prioritizing food equity. There are farms on top of hospitals in Boston, vacant lots that became urban gardens in Philadelphia, and a community feeding itself alongside the polar bears in northern Manitoba. There’s even a chance to learn from one of Canada’s largest cities on how it promotes local food year-round.

We want to hear from you. Tell us in the comments about local food justice organizations in your area.

In this series

Spotlight On the Earn-While-You-Learn Model Transforming a Colorado Food Desert

Huerta Urbana’s community members learn about urban farming, while supplying their neighbors with fresh produce and gaining careers in the agriculture industry.

On the Ground With the Black-Led Organizations Feeding Louisville

Community members use self-reliance as a tool in the fight against food apartheid.

This Market Stepped Up to Feed a Town With No Grocery Store

In upstate New York, New Lebanon Farmers’ Market is filling a need and honing a model for others to follow.

If Montreal Can Feed Itself Year-Round, More Cities Can

Montreal is the world capital of urban agriculture, proving that winter weather is no reason to stop eating locally.

How One Boston Hospital Is Feeding Patients Through Its Rooftop Farm

Food is medicine at Boston Medical Center.

Loiter: East Cleveland Fights for Food Power in a Harsh Climate

How one organization is growing self-determination and food justice amid a barren landscape for Black-owned businesses.

On the Ground With Philadelphia Neighborhoods Transforming Vacant Lots into Flourishing Gardens

A quarter of Philadelphia's population lives below the poverty line and many face food insecurity. There are also thousands of abandoned lots across the city. Community gardens and farms help provide a solution but some are being threatened by rising development.

What It Takes to Feed the Community in the Polar Bear Capital of the World

A sub-arctic research center in Churchill, Manitoba tackles food insecurity with vertical growing and incinerator composting.

Huberto Juan Martinez (54) is not at home when we stop in front of his house in Cerro Armadillo Grande. “He is working on the plantation,” his wife announces. Huberto and his younger son are inspecting the plants that ensure the family’s livelihood. With their machetes in hand, they clear away any unwanted flora encroaching on their plot. As we stroll through the plantation, Huberto’s son nudges the oranges on a nearby tree, handing a few to us to enjoy along the way.

Coffee plants and vanilla thrive together beneath the canopy trees here. The agroforestry system that Juan Martinez has established on this small parcel of land draws inspiration from both—ancestral knowledge and the native environment where vanilla naturally grows.

While this way of growing vanilla is helpful in times of climate change, this year, local producers lost the majority of their production due to the extreme heat in the region.

Mexico belongs to the top five producers of vanilla. Between 2017 and 2021, the country produced 546 tons a year on average. Out of 7,704 tons produced globally in 2022, 518 tons were from Mexico, UN Food and Agriculture Organization reports. Most Mexican vanilla is produced in the state of Veracruz and only about 10percent comes from Oaxaca; such a loss, however, impacts local farmers in terms of their livelihood and cultural preservation.

Nature and culture

Vanilla is originally from Mexico. Vanilla in the Chinantla region in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, where Cerro Armadillo Grande is located, grows not only on plantations but also in the wilderness of local rainforests. La Chinantla region is known for a variety of microclimates, from tropical rainforests to cloud forests and mountainous terrains. Seven varieties of vanilla species can be found here, and it is possible that there are more that are completely wild and hard to trace in the jungle. “We named them all by the places where we found them,” says Elias Garcia Martinez (79), a Chinantec man who has spent the last 40years recovering Chinantec nature and culture. The most common is vanilla colibrí, named by a local hummingbird that pollinates vanilla in the wild.

READ MORE

Huitlacoche, a Mexican fungus, is popping up on restaurant menus across the US

Back then, in his village of San Felipe Usila, people were burning the forests to set up their plots to grow food. “We wanted to stop the fires and decided to introduce crops that would help us do so,” Garcia Martinez remembers. “We wanted to re-introduce native plants, such as cacao, pacaya palm that is edible, and vanilla. All these plants grow underneath the shade of trees.” While he was the one who brought up the idea, it turned out to be a project of the community. “We aimed to recover areas that suffered from environmental damage as well as re-evaluate our culture,” he says. To Garcia Martinez, vanilla is a strategy to preserve the jungle and the Chinantec culture. “If we stop naming certain species in Chinantec language because they are not present anymore, we start losing the language,” he explains.

Ancestral practices

To preserve the culture, local farmers have put a lot of effort into implementing a variety of solutions to keep on producing vanilla. And, at the same time, these solutions are inspired by their culture, their communal way of organizing themselves as well as their cosmovision of being strongly connected to nature and to their place.

All vanilla grown in the region is protected by other trees. Just like Indigenous people in Oaxaca, and beyond, grow their main crops—corn, beans, and zucchini together on one plot called milpa—they often do the same with other plants, including vanilla. The plant is thus protected from the harsh sunlight while it absorbs nutrients from the surrounding vegetation. The agroforestry system also provides farmers with the chance to diversify their crops. Huberto markets coffee, vanilla, and even cedro trees for timber.

The oldest vanilla plants at Juan Martinez’ plantation are six years old. They are climbing up the supporting trees as if their leaves were hugging them. “There is a protocol of how to grow vanilla, what kind of trees serve as good supportive trees, and how to take care of the plant,” says Arturo Elias Garcia Gonzales (40). He is Elias’ son and our guide in La Chinantla. He buys vanilla from local farmers, dries it and sells it. Additionally, he manages his experimental plantation, Colibrí, in the nearby village of Cerro Armadillo Chico. He refers to it as experimental because it is a plot of land granted by the local community for him to test various methods and practices for growing vanilla.

As we wander through Arturo’s plantation, it feels like we’re navigating a dense jungle. He deliberately planted only vanilla in this area. Among his 500 plants, a few have red bows tied around them. This, too, is an age-old tradition. “Here we believe in curses, or mal de ojo, we believe some people have a very strong look and without wanting, they could harm the plants. So, these red bows are to protect my plants from curses. And, at the same time, the plants that have red bows are the ones that are going to produce,” explains Garcia Gonzales.

He also mentions mutual help, which is another practice common in Chinantec communities, that he incorporates at his work. “It is a practice called mano vuelta or turned hand. Sometimes, people just do not have money to pay for work, so they ask somebody to give them a hand. For example, if I cannot come to the plantation, I ask Huberto if he can come and tend the plants,” Garcia Gonzales explains as Huberto is clearing the foliage around the vanilla plants on plantation Colibrí as we are visiting. “And then when he needs help and I am available, I support him.” Garcia Gonzales also uses this when promoting vanilla, for example, when restaurants invite him to talk about his experience with vanilla production.

Loss of produce

Yet, the way that the Chinantec people grow vanilla was not enough to protect the plants. Climate change is impacting vanilla production in many parts of the world, including in Madagascar—the biggest producer of this plant used worldwide as a fragrance and for the cuisine. “Vanilla production is at serious risk as a result of the effects caused by climate change,” says Alejandro Quirino Villarreal, professor at the Faculty of Agronomy at the University of Veracruz, for Diario Xalapa. He says scientists at his university are exploring adaptation mechanisms and how to make the plant more resistant to high temperatures in Veracruz, the place of origin of vanilla.

Vanilla needs to be grown in places where the temperature is between 25 and 35 degrees Celsius throughout the year. It also needs stable annual rainfall of approximately 1500 to 2500 millimetres to grow healthily.

LEARN MORE

Why we can’t get Mexico’s butter avocados in the US.

Juan Martinez already collected vanilla four times; however, this year, he lost most of his produce. “Vanilla pods fell due to extreme heat and droughts,” he says.

“All of our producers estimate that we lost about 80 percent of this year’s produce,” says Garcia Gonzales as he shows us the remnants of branches where flowers used to grow.

The drought season in Oaxaca aligns with the period of vanilla fruit growth. This year, rains arrived in June, but by mid-May, the plants had already started losing their fruit. To prevent the same thing happening again, La Chinantla producers are considering water capturing projects or irrigation systems, which are in demand across the state after this year’s dry season. “Due to our economic situation, we do not have an irrigation system here,” saysvanilla producer Francisco Mendoza from San Rafael Agua de Pescadito. Garcia Gonzales also admits that the lack of resources is one reason why water-capturing projects are lacking in the area. Nevertheless, the producers are actively investigating opportunities for potential partnerships and collaboration with local communities.

Vanilla is not the main crop Juan Martinez produces; it is more of a complementary one, yet such a loss still affects him, mostly because of all the investment that growing vanilla requires. “You need to come and check the plants frequently to make sure they are growing well. You pollinate them by hand when the orchid blossoms,” he explains.

Searching for market in Mexico

The scarcity of water is just one of the hurdles facing vanilla production in the La Chinantla region. Another significant issue is migration. Take Juan Martinez’s eldest son, for instance—he prefers to head north to find employment in Mexico rather than continue working as a farmer. And he is not the only one. When Slow Food—a global movement to ensure quality food that supports farmers across the world—became interested in vanilla production in La Chinantla in 2000, there were 150 families involved in the project. Slow Food helped bring visibility to Mexican vanilla production in the region. Nowadays, Akih vanilla, the project of Arturo Elias Garcia Gonzales, unites only 14 families. “Vanilla is a delicate plant. A lot of people are interested in producing it but with the first plague, they abandon the fields and search for another crop, or they migrate,” says Mendoza, who was a migrant in the US himself. He also calls for more technical support; for example, in regards to how to prepare organic fertilizer for his plants.

Garcia Gonzales and his father continually strive to draw more attention to vanilla, engaging producers as well as the wider public, including restaurants and buyers. “At the beginning, the majority of our vanilla was going to Europe. Nowadays though, we are promoting it within Mexico because the same people in Mexico do not know that vanilla grows in La Chinantla,” says Garcia Gonzales.

His intention is to set up another experimental plantation in San Felipe Usila. “The goal is to cultivate at least a thousand plants there, creating a kind of repository for the seven varieties,” he explains, detailing his vision for preserving vanilla and, by extension, safeguarding the heritage of his Chinantec culture.

Located on the eastern side of the San Francisco Bay sits Alameda County, where Dig Deep Farms’ two farm sites grow rows and rows of fresh food. Dig Deep Farms is a Black-led and BIPOC nonprofit organic farming operation that serves the community with its harvests and its commitment to providing economically viable jobs and careers in farming.

“Farming in America in particular, but also commercially and globally, it’s based on exploitation and making as much money for as little as you can pay. And we have to turn that around in a big way,” says Sasha Shankar, one of the farm directors.

Our food system relies on the security of small farms, but these farms face many obstacles—including land access, access to business resources, and access to buyers. To counter those challenges, Dig Deep Farms has entered into a partnership with the Alameda County Community Food Bank (ACCFB) as a way to accomplish its goals. For the next two to three years, ACCFB will provide institutional support, such as assuming the lease agreements for the farm locations. This will allow Dig Deep Farms to focus on growing a sustainable business, one that will stand on its own in just a few years.

Shifting priorities

Many people think of food banks as a place simply to get a meal. But in the several decades that the Alameda County Community Food Bank has been in operation, the organization has moved beyond hunger relief to addressing poverty systemically.

READ MORE

On the ground with grocery stores changing the way we shop.

“ACCFB has a long history of not addressing hunger in a vacuum or addressing food insecurity in a transactional way, but really wanting to look at those root causes and think about how we can offer solutions to hunger at that root cause level,” says Allison Pratt, chief of strategy and partnerships for ACCFB. “We took a look at how much money we were spending each year on food…and we realized that where we placed those dollars actually does make a difference in the food system.”

“One of the frames that we’re working with as a food bank is our desire to move from a kind of food charity model, or exclusively a food charity model, to a food justice model,” says Susie Wise, ACCFB director of strategy. “Our understanding of where our food comes from, who grows it, who has resources in order to become farmers—these are aspects of bringing a food justice lens to our work.”

For them, this manifests in several different ways—for example, ACCFB team members went to Washington D.C. to lobby Congress for anti-hunger policies in the Farm Bill. Now, they are also investing in a farm that they see doing important work to strengthen the food system.

Dig Deep Farms was cofounded in 2010 as a social enterprise project by Martin Neideffer Hilary Bass. The farm’s mission has stretched beyond the act of growing food, to strengthening the community’s food system. For example, it has been a part of the local food as medicine initiative Recipe4Health, which integrates food into the treatment and prevention of chronic illness. One of Dig Deep Farms’ key ongoing priorities is paying employees a living wage and providing similar benefits to other jobs, to make farming a viable profession.

“One of the reasons why folks are not entering the field, they’re hearing [there’s] no money to be made,” says Troy Horton, one of the farm directors. “They can’t make a living. It’s backbreaking work. And then if we go to those historically underserved, underrepresented folks, it’s even more grim. One of the things. Our primary focus was trying to create a real living wage for folks doing it.”

For the next few years, ACCFB will “incubate” Dig Deep Farms by assuming the lease agreements of Dig Deep Farms’ two farm sites, plus providing logistical, human resource, and financial support.

While a partnership between a farm and a food bank is not common, this partnership can become an example for others.

“The incubator concept invites food banks to consider that question—what does it take to end hunger, in addition to continuing to grow food banks? What are the other pieces of our food system that are going to be vital if we’re actually going to achieve our mission?” says Pratt. “Supporting farmers and supporting equity in how our food is produced, creating economic activity through those channels, all helps to create a system where people have access to what they need.”

Horton points out that one of the big obstacles facing small farmers is the lack of support they get in comparison to large commodity crop farmers. Finding pathways to support, through partnerships, grants, and more, can strengthen small farms.

“That’s what we’re always preaching—us urban farmers or small farmers need to be subsidized, just like the big farmers,” says Horton.

This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist’s weekly newsletter here.

Helene and Milton, the two massive hurricanes that just swept into the country — killing hundreds of people, and leaving both devastation and rumblings of political upheaval in seven states — amounted to their own October surprise. Not that the storms led to some irredeemable gaffe or unveiled some salacious scandal. The surprise, really, may be that not even the hurricanes have pushed concerns about climate change more toward the center of the presidential campaign.

With early voting already underway and two weeks before Election Day, when voters will decide between Vice President Kamala Harris, who has called climate change an “existential threat,” and former President Donald Trump, who has called climate change a “hoax,” Grist’s editorial staff presents a climate-focused voter’s guide — a package of analyses and predictions about what the next four years may bring from the White House, depending on who wins.

The next administration will be decisive for the country’s progress on critical climate goals. By 2030, just a year after the next president would leave office, the U.S. has committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels, and expects to supply up to 13 million electric vehicles annually. A little further down the line, though no less critical, the country’s climate goals include reaching 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035 and achieving a net-zero emissions economy by 2050.

As you gear up to vote, here are 15 ways that Harris’ and Trump’s climate- and environment-related policies could affect your life — along with some information to help inform your vote.

Over the last year or so, utility companies across the country have woken up to a new reality: After two decades of flat growth, electricity demand is about to spike, due to the combined pressures of new data centers, cryptocurrency mining, a manufacturing boom, and the electrification of buildings and transportation.

While the next president will not directly decide how the states supply power to their new and varied customers, he or she will oversee the massive system of incentives, subsidies, and loans by which the federal government influences how much utilities meet electricity demand by burning fossil fuels — the crucial question for the climate.

Trump’s answer to that question can perhaps be summed up in the three-word catchphrase he’s deployed on the campaign trail: “Drill, baby, drill.” He is an avowed friend of the fossil fuel industry, from whom he reportedly demanded $1 billion in campaign funds at a fundraising dinner last spring, promising in exchange to gut environmental regulations.

Vice President Harris is not exactly running on a platform of decarbonization, either. In an effort to win swing votes in the shale-boom heartland of Pennsylvania, she has reversed course on her past opposition to fracking, and she has proudly touted the record levels of oil and gas production seen under the current administration. Despite the risk of nuclear waste, the Biden administration has also championed nuclear power as a carbon-free solution and sought to incentivize the construction of new reactors through subsidies and loans. Although Harris says her administration would not be a continuation of Biden’s, it’s reasonable to expect continuity with Biden’s overall approach of leaning more heavily on incentives for low-emissions energy than restrictions on fossil fuels to further a climate agenda.

READ MORE

What a Harris or Trump presidency will mean for farmers and eaters.

In 2022, the Biden administration handed the American people a great big carrot to incentivize them to decarbonize: the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA. It provides thousands of dollars in the form of rebates and tax credits for a consumer to get an EV and electrify their home with solar panels, a heat pump, and an induction stove. (Though the funding available for renters is slim, it is also out there.) In 2023, 3.4 million Americans got $8.4 billion in tax credits for home energy improvements thanks to the IRA.

If elected, Trump has pledged to rescind the remaining funding, which would require the support of Congress. By contrast, Harris has praised the law (which, as vice president, she famously cast the tie-breaking vote to pass) and would almost certainly veto any attempts by Congress to repeal it. As a presidential candidate, she has not said whether she would expand the law, though many expect she would focus on more efficient implementation.

But while repealing the IRA might slow the steady pace of American households decarbonizing, it can’t stop what’s already in motion. “There are fundamental forces here at work,” said Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at Columbia Business School. “At the end of the day, there’s very little that Trump can do to stand in the way.”

For one, the feds provide guidance to states on how to distribute the money made available through the IRA. More climate-ambitious states are already layering on their own monetary incentives to decarbonize. So even if that IRA money disappeared, states could pick up the slack.

And two, even before the IRA passed, market forces were setting clean energy on a path to replace fossil fuels. The price of solar power dropped by 90 percent between 2010 and 2020. And like any technology, electric appliances will only get cheaper and better. It might take longer without further support from the federal government, but the American home of tomorrow is, inevitably, fully electric — no matter the next administration.

Whether they know it or not, many Americans are already confronting the costs of a warming world in their monthly bills: In recent years, home insurance premiums have risen in almost every state, as insurance companies face the fallout of larger and more damaging hurricanes, wildfires, and hailstorms. In some states, like Florida and California, many prominent companies have fled the market altogether. While some Democrats have proposed legislation that would create a federal backstop for these failing insurance markets — with the goal of ensuring that coverage remains available for most homeowners — these proposals have yet to make much headway in a divided Congress. For the moment, it’s state governments, rather than the president or any other national politicians, that have real jurisdiction over homeowner’s insurance prices.

Near the end of the presidential debate in September, when both candidates were asked about what they’d do to “fight climate change,” Harris began her response by referring to “anyone who lives in a state who has experienced these extreme weather occurrences, who now is either being denied home insurance or is being jacked up” as a way to counter Trump’s denials of climate change.

Traditional homeowner policies don’t include flood insurance, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency runs a flood insurance program that serves 5 million homeowners in the U.S., mostly along the East Coast. Homeowners in the most flood-prone areas are required to buy this policy, but uptake has been lagging in some particularly vulnerable inland communities — including those that were recently devastated by Hurricane Helene. Project 2025, which many experts believe will serve as the blueprint to a second Trump term (though his campaign disavows any connection to it), imagines FEMA winding down the program altogether, throwing flood coverage to the private market. This would likely make it cheaper to live in risky areas — but it would leave homeowners without financial support after floods, all but ensuring only the rich could rebuild.

The appetite for infrastructure spending is so bipartisan that the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signed in 2021, has become more widely known as the bipartisan infrastructure law. But don’t be fooled. A wide gulf separates how Harris and Trump approach transportation, with potentially profound climate implications.

Harris hasn’t offered many specifics, but she has committed to advancing the rollout out of the Biden administration’s infrastructure agenda. That includes traditional efforts like building roads and bridges, mixed with Democratic priorities including union labor and an eye toward climate-resilience. The infrastructure law and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act include billions in spending to promote the adoption of electric vehicles, produce them domestically, and add 500,000 charging stations by 2030. They also include greener transportation efforts aimed at, among other things, electrifying buses, enhancing passenger rail, and expanding mass transit. That said, Harris has not called for the eventual elimination of internal combustion vehicles despite such plans in 12 states.

Trump has also been sparse on details about transportation — his website doesn’t address the issue except to decry Chinese ownership. During his first term and 2020 campaign, he championed (though never produced) a $1 trillion infrastructure plan. It focused on building “gleaming” roads, highways, and bridges, and reducing the environmental review and government oversight of such projects. He has favored flipping the federal-first funding model to shift much of the cost onto states, municipalities, and the private sector. Ultimately, Trump seems to have little interest in a transition to low-carbon transportation — the 2024 official Republican platform calls for rolling back EV mandates — and he remains a vocal supporter of fossil fuel production.

Rising global temperatures and worsening extreme weather are changing the distribution and prevalence of tick- and mosquito-borne diseases, fungal pathogens, and water-borne bacteria across the U.S. State and local health departments rely heavily on data and recommendations on these climate-fueled illnesses from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC — an agency whose director is appointed by the president and can be influenced by the White House.

In his first term, Trump tried to divorce many federal agencies’ research functions from their rulemaking capacities, and there are concerns that, if he wins again in November, Trump would continue that effort. Project 2025, a sweeping blueprint developed by right-wing conservative groups with the aim of influencing a second Trump term, proposes separating the CDC’s disease surveillance efforts from its policy recommendation work, meaning the agency would be able to track the effects of climate change on human health, like the spreading of infectious diseases, but it wouldn’t be able to tell states how to manage them or inform the public about how to stay safe from them.

Harris is expected to leave the CDC intact, but she hasn’t given many signals on how she’d approach climate and health initiatives. Her campaign website says she aims to protect public health, but provides no further clarification or policy position on that subject, or specifically climate change’s influence on it. Over the past four years, the Biden administration has made strides in protecting Americans from extreme heat, the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the U.S. It proposed new heat protections for indoor and outdoor workers, and it made more than $1 billion in grant funding available to nonprofits, tribes, cities, and states for cooling initiatives such as planting trees in urban areas, which reduce the risk of heat illness. It’s reasonable to expect that a future Harris administration would continue Biden’s work in this area. Harris cast the tie-breaking vote on the IRA, which includes emissions-cutting policies that will lead to less global warming in the long term, benefiting human health not just in the U.S. but worldwide.

But there’s more to be done. Biden established the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity in the first year of his term, but it still hasn’t been funded by Congress. Harris has not said whether she will push for more funding for that office.

Inflation has cooled significantly since 2022, but high prices — especially high food prices — remain a concern for many Americans. Both candidates have promised to tackle the issue; Harris went so far as to propose a federal price-gouging ban to lower the cost of groceries. Such a ban could help smaller producers and suppliers, but economists fear it could also lead to further supply shortages and reduced product quality. Meanwhile, Trump has said he will tax imported goods to lower food prices, though analysts have pointed out that the tax would likely do the opposite. Trump-era tariff fights during the U.S.-China trade war led to farmers losing billions of dollars in exports, which the federal government had to make up for with subsidies.

Trump’s immigration agenda could also affect food prices. If reelected, the former president has said he will expel millions of undocumented immigrants, many of whom work for low pay on farms and in other parts of the food sector, playing a vital role in food harvesting and processing. Their mass deportation and the resulting labor shortage could drive up prices at the grocery store. Meanwhile, Harris promises to uphold and strengthen the H-2A visa system — the national program that enables agricultural producers to hire foreign-born workers for seasonal work.

In the short term, it must be emphasized that neither candidate’s economic plans will have much of an effect on the ways extreme weather and climate disasters are already driving up the cost of groceries. Severe droughts are one of the factors that have destabilized the global crop market in recent years, translating to higher U.S. grocery store prices. Warming has led to reduced agricultural productivity and diminished crop yields, while major disasters throttle the supply chain. Even a forecast of extreme weather can send food prices higher. These climate trends are likely to continue over the next four years, no matter who becomes president.

But the winner of the 2024 election can determine how badly climate change batters the food supply in the long run — primarily by controlling greenhouse gas emissions.

“I want absolutely immaculate, clean water,” Trump said in June during the first presidential debate this election season. But if a second Trump presidency is anything like the first, there is good reason to worry about the protection of public drinking water.

During his first term in office, the Trump administration repealed the Clean Water Rule, a critical part of the Clean Water Act that limited the amount of pollutants companies could discharge near streams, wetlands, and other sources of water used for public consumption. “It was ready to protect the drinking water of 117 million Americans and then, within a few months of being in office, Donald Trump and [former EPA administrator] Scott Pruitt threw it into the trash bin to appease their polluter allies,” former Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune said in a press release.

While in office, Trump also secured a conservative majority on the Supreme Court, which last year tipped the court in favor of a decision to vastly limit the Environmental Protection Agency’s power to regulate pollution in certain wetlands, forcing the agency to weaken its own clean water rules.

A Harris administration would likely carry forward the work of several Biden EPA measures to safeguard the public’s drinking water from toxic heavy metals and other contaminants. For example, in April, the EPA passed the nation’s first-ever national drinking water standard to protect an estimated 100 million people from a category of synthetic chemicals known as PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” which have been linked to cancer, high blood pressure, and immune system deficiencies. Enforcing the new standard will require the agency to examine test results from thousands of water systems across the country and follow up to ensure their compliance — an effort that will take place during the next White House administration.

“As president,” Harris’ website says, “she will unite Americans to tackle the climate crisis as she builds on this historic work, advances environmental justice, protects public lands and public health, increases resilience to climate disasters, lowers household energy costs, creates millions of new jobs, and continues to hold polluters accountable to secure clean air and water for all.” Project 2025, the policy plan drawn up by former Trump staffers to guide a second Trump administration’s policies, indicates that a future Trump administration would eliminate safeguards like the PFAS rule that place limits on industrial emissions and discharges.

Just this month, the EPA issued a groundbreaking rule requiring water utilities to replace virtually every lead pipe in the country within 10 years. With funds from Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure law, the agency will also invest $2.6 billion for drinking water upgrades and lead pipe replacements. Harris has previously spoken out about the dangers of lead pipes, stating at a press conference in 2022 that lead exposure is “an issue that we as a nation should commit to ending.”

The success of these and other measures will rely on a well-staffed EPA enforcement division, which may end up being one of the most insidious stakes of this election for environmental policies. Budget cuts and staff departures during the first Trump administration gutted the EPA’s enforcement capacity — a problem that the agency has spent the past four years trying to mend. Project 2025 “would essentially eviscerate the EPA,” said Stan Meiburg, who served as acting deputy administrator for the EPA from 2014 to 2017.

President Biden’s clean air policy has been characterized by a spate of new rules to curb toxic air pollution from a variety of facilities, including petroleum coke ovens, synthetic manufacturing facilities, and steel mills. While environmental advocates have decried some of these regulations as insufficiently protective, certain provisions — such as mandatory air monitoring — were hailed as milestones in the history of the agency’s air pollution policy. Former EPA staffer and air pollution expert Scott Throwe told Grist that a Harris- and Democratic-led EPA would continue to build on the work of the past four years by enforcing these new rules, which will require federal oversight of state environmental agencies’ inspection protocols and monitoring data.

Project 2025 proposes a major reorganization of the EPA, which would include the reduction of full-time staff positions and the elimination of departments deemed “superfluous.” It also promotes the rollback of a range of air quality regulations, from ambient air standards for toxic pollutants to greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants.

What’s more, a growing body of research has found that poor air quality is often concentrated in communities of color, which are disproportionately close to fossil fuel infrastructure. Conservative state governments havepushedback against the Biden EPA’s efforts to address “environmental justice” through agency channels and in court — efforts that will likely enjoy more executive support under a second Trump administration.

Under the Antiquities Act of 1906, a national monument can be created by presidential decree. The act can be a useful tool to protect important landscapes from industries like oil, gas, and even green energy enterprises. Tribal nations have asked numerous presidents to use this executive power to protect tribal homelands that might fall within federal jurisdiction. During his first term, Trump argued that the act also gives the president the implicit power to dissolve a national monument.

In 2017, Trump drastically shrunk two Obama-era designations, Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante in Utah, in what amounted to the biggest slash of federal land protections in the history of the United States. At the time, Trump said that “bureaucrats in Washington” should not control what happens to land in Utah. While giving back local control was Trump’s stated rationale, tribes in the area, like the Diné, Ute, Hopi, and Zuni, had been working for years to protect the two iconic and culturally significant sites. Meanwhile, his decision opened up the land for oil and gas development. While not all tribal nations are opposed to oil and gas production, tribal environmental advocates are worried that a second Trump term will erode federal environmental regulations and commitments to progress in the fight against climate change.

Since 2021, the Biden administration has put more than 42 million acres of land into conservation by creating and expanding national monuments. This includes the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni, a new monument spanning a million acres near the Grand Canyon — the kind of protection that tribal activists for years had worked to prevent industrial uranium mining. And just this month, Biden announced the creation of the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary — a 4,500-square-mile national marine sanctuary to be “managed with tribal, Indigenous community involvement.”

But Harris might not continue that legacy. While she has remained silent about what she would do to protect lands, she has been vocal about continuing the U.S.’s oil and gas production as well as a push for more mining to help with the green transition — like copper from Oak Flat in Arizona and lithium from Thacker Pass in Nevada — both important places to tribal communities in the area. Tribes have been subjected to the adverse effects of the energy crisis before — namely dams that destroyed swaths of homelands and nuclear energy that increased cancer rates of Southwest tribal members — and without specific protections, it’s easy to see green energy as a changing of the guard instead of a game changer.

Congress controls how much money the Federal Emergency Management Agency receives for relief efforts after catastrophic events like hurricanes Helene and Milton, but the president holds significant sway over who receives money and when. A second Trump administration would likely curtail some of the climate-focused resiliency projects FEMA has pursued in recent years, such as cutting back money for infrastructure that would be more resilient against hazards like sea level rises, fires, and earthquakes. Republican firebrands, like Representative Scott Perry from Pennsylvania, have decried these projects as wasteful and unnecessary.

Under the Stafford Act, which governs federal disaster response, the president has the power to disburse relief to specific parts of the country after any “major disaster” — hurricanes, big floods, fires. In September, Trump suggested that he might make disaster aid contingent on political support if he returns to office, promising to withhold wildfire support from California unless state officials give more irrigation water to Central Valley farmers. Harris has not given an explicit indication of how she would fund climate-resiliency or disaster-response programs, though she has boosted FEMA’s recovery efforts following Helene and Milton.

The United States has long been a leader in research essential to understanding — and responding to — a warming world. The government plays a key role in advancing climate science and providing timely meteorological data to the public. Neither Trump nor Harris address this in their platform, but history yields clues to what their presidency might mean for this vital work.

Trump has consistently dismissed climate change as a “hoax” and downplayed scientific consensus that it is anthropogenic, or driven by human activities. As president, he gutted funding for research, appointed climate skeptics and industry insiders, and eliminated scientific advisory committees from several federal agencies. Thousands of government scientists quit in response. (In fact, still reeling from Trump’s attacks, new union contracts protect scientific integrity to combat such meddling.) His administration censored scientific data on government websites and tried to undermine the findings of the National Climate Assessment, the government’s scientific report on the risks and impacts of climate change. If reelected, Trump would almost certainly adopt a similar strategy, deprioritizing climate science and potentially even restructuring or eliminating federal agencies that advance it.

Harris has long supported climate action; she co-sponsored the Green New Deal as a senator and, as vice president, cast the deciding vote to pass the Inflation Reduction Act, which bolstered funding for agencies that oversee climate research. As part of its “whole of government” approach to the crisis, the Biden administration created the National Climate Task Force, with the EPA, NASA, and others to ensure science informs policy. Although Harris hasn’t said much about climate change as a candidate, climate organizations generally support her campaign and believe her administration will build on the progress made so far.

A lot goes into calculating the energy rates you see on your monthly electric bill — construction and maintenance of power plants, fuel costs, and much more. It’s pretty tough to draw a direct line from the president to your bill, so if you’re worried about your energy costs, you’d do well to read up on your local public utility commission, municipal electric authority, or electric membership cooperative board.

What the president can do, though, is appoint people to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC — the board of up to five individuals who regulate the transmission of utilities across the entire country. As the U.S. continues to shift away from fossil fuels, a fundamental problem stands in the way: The country’s aging and fragmented grid lacks the capacity to move all of the electricity being generated from renewable sources. In May, FERC, which currently has a Democratic majority, approved a rule to try to solve that issue; it voted to require that regional utilities identify opportunities for upgrading the capacities of existing transmission infrastructure and that regional grid operators forecast their transmission needs 20 years into the future. These steps will be essential for utility companies to take advantage of the subsidies offered in the IRA and bipartisan infrastructure law.

The rule is facing legal challenges, which like much else in U.S. courts, appear to be political. So even if Harris wins November’s election, and maintains a commission that prioritizes the transition away from fossil fuels, the oil and gas industry and the politicians who support it will not acquiesce easily. If Trump wins, he’d have the chance to appoint a new FERC chair from among the current commissioners and to appoint a new commissioner in 2026, when the current chair’s term ends. (Or possibly sooner.) Although FERC’s actions tend to be more insulated from changes in the White House because commissioners serve five-year terms, a commission led by new Trump appointees would most likely deprioritize initiatives that would upgrade the grid to support clean energy adoption. Trump’s appointees supported fossil fuel interests on several fronts during his previous term, for instance by counteracting state subsidies to favor coal and gas plants.

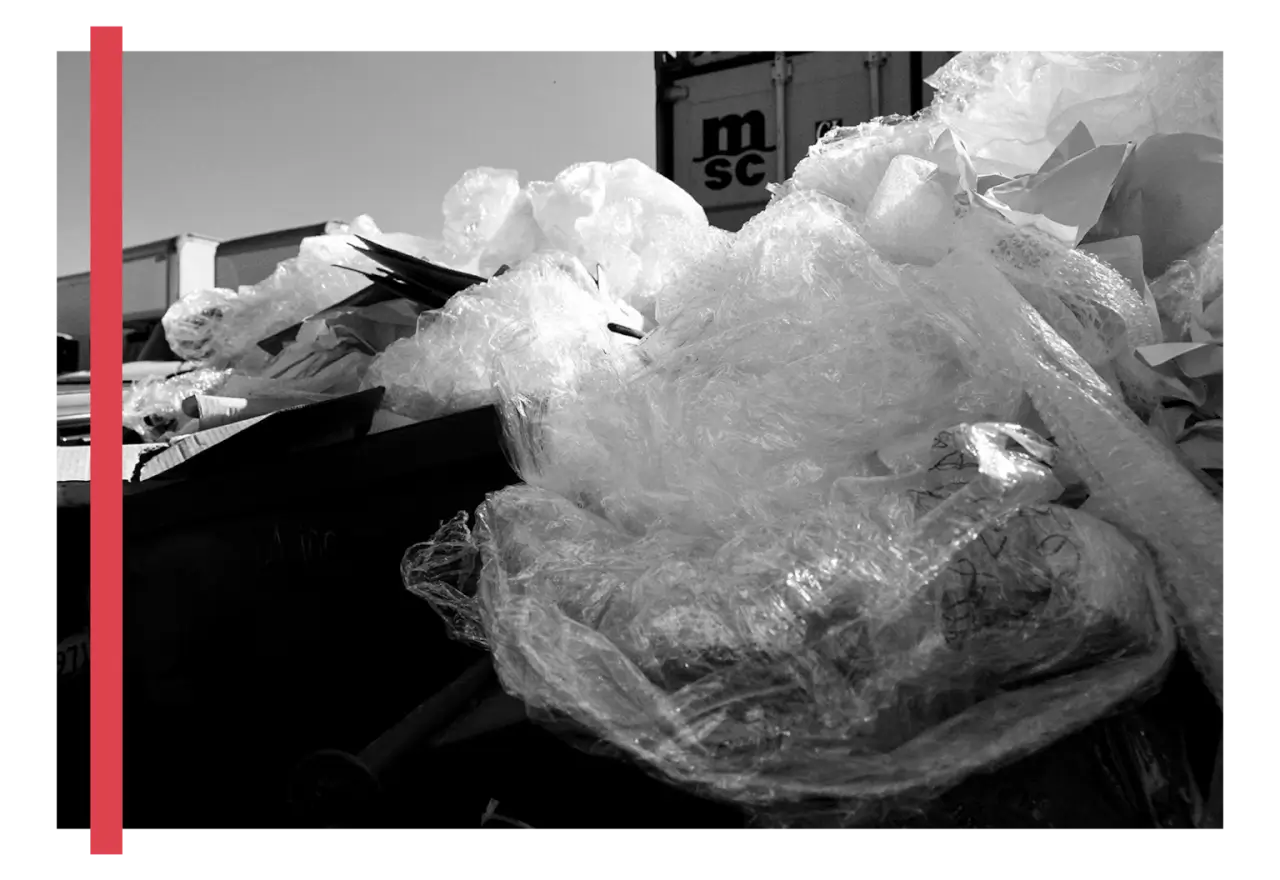

Some 33 billion pounds of plastic waste enter the marine environment globally every year, and the problem is expected to worsen as the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries ramp up plastic production.

Perhaps the most important step the next president could take to curb plastic pollution is to push Congress to ratify and implement the United Nations’ global plastics treaty, which is scheduled to be finalized by the end of this year. The Biden administration recently announced its support for a version of the treaty that limits plastic production, and, though Harris hasn’t made any public comment about it, experts expect that her administration would support it as well. Meanwhile, a former Trump White House official told Politico this April that Trump — who famously withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement in his first term — would take a “hard-nosed look” at any outcome of the plastics negotiations and be “skeptical that the agreement reached was the best agreement that could have been reached.”

The Biden administration has also taken some positive steps to address plastic pollution domestically, including a ban on the federal procurement of single-use plastics. Experts expect that progress to continue under a Harris administration. In 2011, as California’s attorney general, Harris sued plastic bottle companies over misleading claims that their products were recyclable. As a U.S. senator, she co-sponsored a Democratic bill to phase out unnecessary single-use plastic products.

Trump, meanwhile, does not have a strong track record on plastic. Although he signed a 2019 law to remove and prevent ocean litter, he has taken personal credit for the construction of new plastic manufacturing facilities and derided the idea of banning single-use plastic straws. And Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda could increase the extraction of fossil fuels used to make plastics.

LEARN MORE

How to be a food policy advocate in your community.

After decades of failed attempts to tackle the climate crisis, Congress finally passed major legislation two years ago with the Inflation Reduction Act. Not a single Republican voted for it.

Elections aren’t just important for getting the legislative power needed to enact climate policies — they’re also important for implementing them. The IRA and the bipartisan infrastructure law, another key climate-related law, are entering crucial phases for their implementation, particularly the doling out of billions of dollars for clean energy, environmental justice, and climate resiliency. Trump, having vowed to rescind unspent IRA funds if elected, seems poised to hamper the law’s rollout, slowing efforts to get the country using more clean energy.

But it’s a mistake to imagine that only federal elections matter when it comes to climate change. Eliminating greenhouse gases from energy, buildings, transportation, and food systems requires legislation at every level. In Arizona and Montana, for example, voters this year will elect utility commissioners, the powerful, yet largely ignored officials who play a crucial role in whether — and how quickly — the country moves away from fossil fuels. State legislators can also open the door to efforts to get 100 percent clean electricity, as happened in Michigan and Minnesota after the 2022 election. Even in a state like Washington with Democratic Governor Jay Inslee, who once campaigned for the White House on a climate change platform, votes matter — climate action is literally on the ballot in November, when voters could choose to kill the state’s landmark price on carbon pollution.

Depending on what happens with the presidential and congressional races, state and local action might be the best hope for furthering climate policy anyway.

During his first term, Trump pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement, a global commitment to reduce the burning of fossil fuels in an effort to curb the worst impacts of climate change. “I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris,” he said from the Rose Garden of the White House in 2017. Trump didn’t entirely abandon global climate discussions; his administration continued to attend global climate conferences, where it endorsed events on fossil fuels.

The Biden administration rejoined the Paris Agreement and pledged billions of dollars to combat climate change both domestically and abroad, but a second Trump administration would likely undo this progress. Trump says that he would pull out of the Paris Agreement again, and reportedly would also consider withdrawing the U.S. from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, a 1992 treaty that’s the basis for modern global climate talks. Harris is expected, at least, to continue Biden’s policies. Speaking from COP28 in Dubai last year, an annual United Nations climate gathering, she celebrated America’s progress in tackling the climate crisis and petitioned for much more to be done. “In order to keep our critical 1.5 degree-Celsius goal within reach,” she said, “we must have the ambition to meet this moment, to accelerate our ongoing work, increase our investments, and lead with courage and conviction.”

But both the Trump and Biden administrations achieved record oil and gas production during their time in office, and Harris opposes a ban on fracking. In order to make a dent in the climate crisis, whoever becomes president would have to reject that status quo and put serious money behind global promises to mitigate climate change. Otherwise, climate change-related losses will just continue to mount — already, they are expected to cost $580 billion globally by 2030.

Anita Hofschneider, Senior staff writer focusing on Indigenous affairs

Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org

When Briana Bosch started her Colorado flower farm, Blossom and Branch, the fifth-generation farmer—her family had a dairy and corn farm—mimicked what her family had always done: plastic landscape fabric to control weeds, plastic seedling trays, plastic netting, even plastic irrigation tubing. It wasn’t long before she grew disenchanted with the amount of plastic she was using.

“Our major goal is to support the ecosystem, heal nature, and be more attuned with nature’s processes,” says Bosch, who farms using organic and regenerative agricultural practices. “As I researched more about soil health, I started to learn how plastic impacts microorganisms in the soil.”

READ MORE

A plastic tsunami is taking over farms. What can stop it?

Start thinking about all the ways we use plastic in the garden—seedling trays, landscape fabric, plant pots, to name a few—and it’s hard to unsee all that planetary warming fossil fuel-produced plastic. Most of it tends to get used for a season or two before ending up in a landfill, where the consequences for the planet and ourselves can be dire.

We all know about the issue of plastics in the ocean. The United Nations has declared the plastic pollution of our oceans “a planetary crisis.” Each year, according to National Geographic, about eight million tons of plastic waste ends up in oceans. Yet, there’s likely even more plastic pollution in our soils than in our oceans. Scientists estimate that more than half of the world’s human population might have plastic passing through their bodies.

Researchers are still trying to understand what all that plastic is doing to us and to the soil, but some recent studies have found that microplastics can change the structure of the soil and potentially interfere with plant growth if they enter the plant tissues through the soil.

But there are steps we can take to reduce the use of plastic in our gardens, ultimately helping to protect our health and the planet.

Here’s how to start reducing the plastic used in your garden.

Swap your plastic plant labels

for wooden sticks, stones, or even popsicle sticks.

“I love the look and the fun of painting rocks as reusable labels! You can get paint markers, too, to keep things less messy with the kids,” says Nicole Baker, a biologist with The Wild Center, an interactive science museum in New York’s Adirondacks.

Instead of buying plastic ties and stakes

use natural twine to tie up plants and wooden or bamboo stakes to support them. You could even use a sturdy branch from your backyard or a big stick as a stake. These materials break down naturally and are safer for the environment.

Give the plastic pots or containers you have a second life.

You can wash, sanitize, and reuse them. “If they start to break down, you can often use them as drainage material in larger pots or garden beds,” says Georgia-based entrepreneur and gardener Adria Marshall. Marshall, the founder of a plant-based hair care company, Ecoslay, has been gardening alongside her mother and grandfather since the age of 12 and is on a mission to reduce single-use plastics in her garden.

If you have loads of old plastic pots or seed starter trays you’re not using, you may also be able to return some to your local greenhouse. “This plastic costs money for those nurseries, many of which are mom-and-pop-owned shops and farms,” says Baker. “Many businesses will welcome the return of their plastics, and they will reuse them. This helps out the local business and keeps that plastic out of the landfill. It’s always good manners to call ahead and ask if they would be willing to take the old, still useful, plastic pots.”

When you do need seed starter trays or pots, consider your options.

“Instead of buying plastic seed trays or pots, use items you already have around the house,” says Marshall.

You can likely repurpose items such as coffee cans, egg cartons, and maybe even old casserole dishes.

Bosch has found a lot of success using cedar seed starter trays. “It holds up phenomenally well. You would think they would rot, but they don’t.”

You can also look for grow bags made from natural fibers such as cotton, burlap, jute, hemp, terracotta, and clay pots or biodegradable options like those made from coconut coir, peat, or compressed paper.

Baker has even had success planting directly into straw bales. “They act as both the container and as a growing medium. Straw bales get bonus points because they can be composted after the growing season for future use as a natural fertilizer.”

Instead of using plastic weed barriers or synthetic mulch

use compostable materials such as straw, grass clippings, wood chips, newspaper, or leaves. “It reduces plastic waste, and organic mulches also break down over time and add nutrients to the soil,” says Marshall.

Bagged soils, along with the seed starter trays, are two of the biggest culprits of single-use plastic in home gardens, says Bosh, adding that, most of the time, your soil probably doesn’t need much. If you need mulch or soil amendments, try to buy the biggest container you can. Some garden centers or even town landfills that have composting may offer refill stations where you can bring your own containers.

“It hasn’t been as hard as I thought,” says Bosch, who was determined to find ways to farm without using plastic. She started by removing about two-thirds of all the landscape fabric she used before eventually removing all landscape fabric and plastic netting, using natural mulch or cover crops to control weeds instead. The hardest part has been finding an alternative to the plastic irrigation tubing, as tubes with fabric are lined with resin and copper is simply cost prohibitive. “We’re buying the highest quality we can find so we’re not replacing it every year and can patch it as needed.”

You can start by targeting one thing at a time, and it might not be perfect.

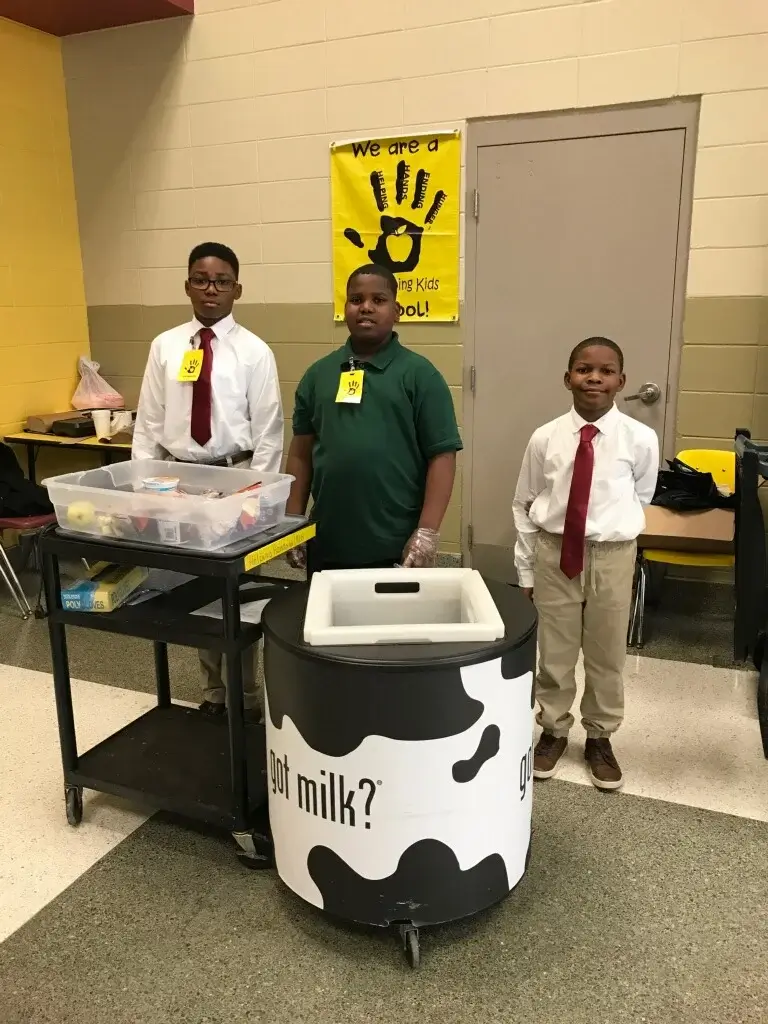

In 2016, Carla Harward’s daughter, Sophie, came home from her middle school in Chattooga County and told her mother about two students who hadn’t eaten over the weekend.

“I was stunned,” says Harward. “Sophie said the little boys were crying because their bellies hurt. We just had no idea there were kids in our community that were hungry.” Harward and some families gathered food for the family, but she knew more had to be done.

It was her daughter who mentioned all the food going to waste at her school and asked her mom a simple question: Why couldn’t they give families the food from her school instead of throwing it away?

Sophie’s idea became the spark that launched the Georgia nonprofit Helping Hands Ending Hunger, which now works with 150 schools throughout the state to divert food waste.

And there’s a lot of food going to waste. A 2019 USDA School Nutrition and Meal Cost Study found that 31 percent of vegetables and 41 percent of milk were tossed.

But those figures are changing. Schools in Atlanta are working to feed hungry families and rethink how they approach school food. Here are three making huge environmental impacts.

Helping Hands Ending Hunger

Harward thought her daughter’s idea to repurpose the food kids didn’t eat sounded simple, but the USDA has strict rules on preventing cold cafeteria food from being saved.

But Harward wasn’t deterred. In 2016, she formed a 501(c)(3) and tested the pilot in her daughter’s school. After lunches, students collected uneaten prepackaged food or dry goods, such as apple sauce, packaged carrots, and unopened milk cartons. The students learned how to safely collect and store the unused food, and then handed it out weekly to families in need.

In Georgia, that included more than 13 percent of children who lacked access to healthy food in 2022 (the latest numbers available), according to the nonprofit Feeding America.

Today, the Helping Hands program is in 150 Georgia schools and is run by students. “We now train volunteers and school staff at every school chapter to teach kids that food is not trash,” says Harward.

Students at Atlanta Public School’s Springdale Park Elementary School (SPARK) STEAM program rescued about 700 pounds of food between February and May 2024 alone, according to Harward. It was repurposed into 566 meals and another 486 pounds of food for the community.

“Food that can’t be saved is collected in compost buckets in the cafeteria and used in our [rooftop] garden; nothing goes to waste,” says Kristin Siembieda, STEAM program specialist and Helping Hands coordinator at SPARK.

Harward says the program works incredibly well. “These kids are taking charge and are going to be amazing future leaders.”

Food Waste Warriors

The students at Gwinnett County School’s Lovin Elementary have a warrior mentality when it comes to food waste.

In 2018, Gwinnett Clean & Beautiful’s Green and Healthy Schools had a rare opportunity to participate in a new initiative of the World Wildlife Fund, the Food Waste Warriors program.

“The World Wildlife Fund was looking for systems to collect data for its first food waste report, and to help write curriculum around how to do food waste audits,” says Gwinnett Clean & Beautiful board member Jay Bassett, who also works for the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “The Green and Healthy Schools program was already established [at Gwinnett County Schools], so we did it.”

In 2019, Gwinnett County Schools enlisted Lovin Elementary in Lawrenceville to be part of the Food Waste Warriors program, conducting food waste audits. They sorted milk, fruits, and vegetables left on lunch trays into buckets and weighed it all. They were shocked that the school had trashed almost 600 pounds of food — in one day.

Thirteen Gwinnett County Schools completed the 31 food waste audits for the WWF’s Food Waste Warriors report. The data for Gwinnett County Schools was eye-opening: On average, 95,169 pounds of food per school, per year was wasted, and 49.4 pounds of food per student, per year was wasted, as well as almost 56,000 cartons of milk per school, per year.

READ MORE

California’s food recovery program is the first of its kind in the country.

The first 31 audits launched the ongoing relationship with the WWF and Gwinnett County Schools, which continues to focus on K-12 education. Today, the Food Waste Warriors program is a critical part of the Green and Healthy Schools and STEAM education within Gwinnett County Schools, which is the largest in Georgia.

“The most important thing about the Food Waste Warrior program is the students tackle every aspect of the project,” says Brenda McDaniel, environmental education manager, Gwinnett County Schools. “It’s not just about doing food waste audits; the students must come up with solutions to tackle the problems.”

That first student-led audit at Lovin Elementary provided the school with different resolutions it has now implemented, including serving food differently to reduce packaging waste, eliminating straws and breakfast cutlery, and using biodegradable trays.

Third-graders now collect food scraps that would be trashed at the end of lunch and add them to the compost bin that’s part of the Food Well Alliance’s Compost Connectors program. They learn about composting in STEAM classes and how to use it to fertilize their gardens and help feed the school’s chickens.

First- and third-graders have improved their skillsets in science and math so much, the county revised its middle school curriculum to accommodate their new abilities.

“I never envisioned where this would go,” says Bassett. “We just wanted to change policy on how to reduce waste in cafeterias. That led to systemically building this culture around agriculture, nature-based learning, biology and engineering. Reducing food waste is just a small part of it.”

Raccoon Eyes

Georgia Tech in Atlanta is synonymous with engineering, prestigious research and cutting-edge technology. Soon, its dining services could be a leader in what universities can do to cut down on food waste in their dining halls, thanks to Tech students Bruce Tan, Ivan Zou, and Nathanael Koh.

The three students focused their CREATE-X Capstone, which is an undergraduate senior design course for entrepreneurial projects, on reducing food waste on campus because of the amount of food being trashed in the university dining halls. Their solution: Raccoon Eyes.

“The eye-opener for me was a time I was in the kitchen at the end of lunch service,” says Zou. “A worker pushed in carts full of food that were going straight to the trash.”

Raccoon Eyes has two components: 3D cameras and a computer screen on the dining hall trash cans. The 3D cameras take pictures of every plate and calculate the type and weight of food waste going into the trash using software the three students developed. The computer screen uses visual and audio to collect feedback about the food and to nudge students about future food waste.

During the period between Jan. 11 and May 2, 2024, the system tracked and measured the amount of food waste on more than 240,000 plates at Tech. While there was still about an ounce of food left on each plate, the overall amount of food being tossed dropped by 19 percent during the semester.

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.