A modern-day Johnny Appleseed, ‘Jackfruit Jayan’ has planted more than 20,000 jackfruit seedlings.

When he was just 11 years old, K.R. Jayan—who lived in the tiny village of Irinjalakuda in Kerala, a state in South India—was tasked by his teacher to engage in a socially useful activity, such as planting a tree, in honor of Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday. Most students in his class brought a flowering plant. Jayan brought a jackfruit seedling, which caused his classmates to tease him, calling him “Plavu Jayan,” which translates to “Jackfruit Jayan.” The nickname stuck, and Jayan’s tryst with jackfruit would blossom even more in the years to come.

Jackfruit, which is native to South India, is widely grown in tropical and subtropical parts of the world, including Malaysia, Central and Eastern Africa, the Caribbean, Brazil, Australia, Puerto Rico and many Pacific Islands. At one point, jackfruit was considered an inferior food, but it’s found new popularity as the global demand for plant-based nutrition has increased, with the fruit now embraced by chefs and home cooks as an excellent pork substitute.

Back in its home country, jackfruit has been an important part of the national diet for centuries. In India, jackfruit is enjoyed both in its raw form, eaten as a fruit, as well as cooked, such as in a curry. The plant’s leaves are used to wrap food during steaming. It’s featured in other local dishes, including jackfruit jam, payasam (a dessert made with milk) and jackfruit chips.

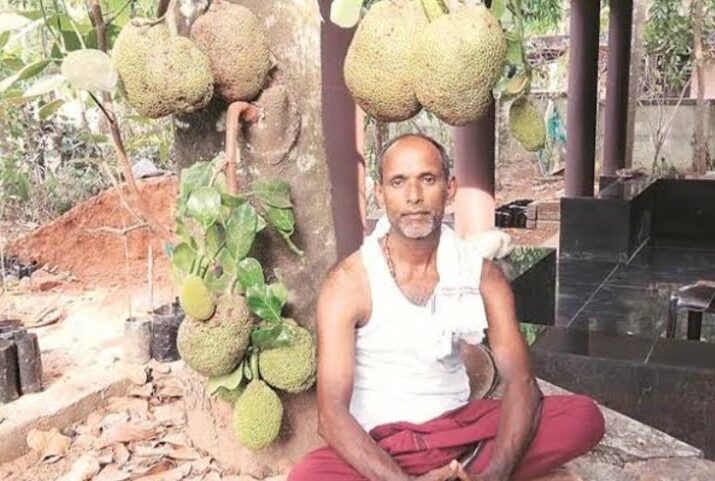

‘Jackfruit Jayan’ with his jackfruits. Photo courtesy of K.R. Jayan.

“As a child with eight siblings and a large family with very little land and income, we subsisted on the fruits of a huge jackfruit tree in our garden,” says Jayan. “We even fed our goats with the leaves from the tree.”

The importance of jackfruit started to slowly fade away after many people from South Indian states began migrating to the Gulf countries in search of better opportunities in the 1960s. With their increased earnings, the migrants built huge palatial homes and sent cash home to their families. But they gradually lost touch with the natural coconut and jackfruits the lands provided, causing “jackfruit trees [to fade] from our landscapes,” says Jayan.

One of the many people who moved to the Gulf for better prospects, Jayan worked in a supermarket in Dubai from 1995 to 2006. “But I was not happy working there,” he says. “I needed the soil and greenery and missed my connection with nature. So I moved back [home] to Kerala, which is green, lush and called ‘God’s own country.’”

Upon his return, Jayan noticed how few jackfruit trees remained around the villages, and his younger passion for the fruit was reignited. “The jackfruit is a wonderful plant. Not only the fruit but every part of the tree is useful,” he says. “The fruit, of course, is packed with minerals like iron, potassium and calcium. The timber is used for building and furniture and the seeds have anti-cancer properties. The powdered bark is used for treating swellings on legs. The jackfruit tree’s roots used to buttress the soil and prevent landslides and floods, which have become so common in recent years.”

Jayan set out to conserve the fruit himself, collecting seeds from home gardens and orchards, as well as researching different varieties of the tree, such as the Muttom Varikka, a firm-fleshed variety with a sweet scent, and Thenvarikka, which produces one of the sweetest varieties of jackfruit. The average jackfruit weighs about 15 to 20 pounds, while those on the large side can clock in as high as 55 pounds. The biggest fruit that Jayan has harvested, a variety called Muttom Varikka, weighed a whopping 122 pounds.

‘Jackfruit Jayan’ prefers to work with seedlings. Photo courtesy of K.R. Jayan.

Wanting to replicate the trees as closely as possible, Jayan always preferred to collect seeds to grow from seedlings as opposed to grafting branches from one tree onto another, which he finds to be an “artificial” method. When planted from seed, it can take anywhere between five and eight years for a jackfruit tree to bear fruit. But when planted this way, the tree can live for up to 150 years. “Though grafting is a quicker process and may bear fruit within three years, the tree lives only up to eight years,” explains Jayan.

Jayan’s jackfruit-planting obsession quickly took off. “As I did not have land of my own, I started planting these seedlings in road sides, near railway stations and on college campuses. Many people thought I was mad, with my obsession with the fruit,” he says.

By then, Jayan already had a wife and kids and needed to find some way to support his family. So he got a three-wheeler auto rickshaw and used it to travel from village to village selling soaps, incense and candles made by local women’s self-help groups. The journeys presented new opportunities to plant more trees. “I used to carry the jackfruit seedlings and plant them on empty plots along roadsides. I would water them and nurture them, happy to see them grow and produce fruits,” he says.

To date, Jayan has planted more than 20,000 jackfruit seedlings and has cultivated as many as 23 different varieties. In India, “Jackfruit Jayan” has been celebrated for his individual efforts to diversify jackfruit plantings. In 2019, he was recognized by the prestigious Plant Genome Saviour Community Awards. He has been invited to visit colleges and the Raj Bhavan, the official residence of the Governor of Kerala, to plant jackfruit seedlings. He has even planted jackfruit trees at Gandhi’s Sevagram Ashram in Maharashtra, where the influential leader lived and worked for many years. Jayan has also written two books on the importance of the fruit, both titled Plavu, that are used by school students.

Many people with land still approach Jayan to create jackfruit orchards and he willingly obliges. “I supply seedlings to people who want them free of cost,” he says.

In the future, Jayan wishes to see more people plant orchards of biodiversity, not only of jackfruit but also other trees such as coconut and tamarind. “My vision is to create forests of jackfruit, a fruit which can feed the hungry and prevent soil erosion and slowly extend this across the country,” he says. “Nothing gives me more pleasure than to see a tree grow from a seedling and bear fruit.”