Water Wells are at Risk of Going Dry in the US and Worldwide

Drilled wells provide nearly half of the water American farmers use to irrigate their crops.

Water Wells are at Risk of Going Dry in the US and Worldwide

Drilled wells provide nearly half of the water American farmers use to irrigate their crops.

water irrigation pipes run through dry farmland in Southern California.by Eddie J. Rodriquez/Shutterstock

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As the drought outlook for the Western US becomes increasingly bleak, attention is turning once again to groundwater—literally, water stored in the ground. It is Earth’s most widespread and reliable source of fresh water, but it’s not limitless.

Wells that people drill to access groundwater supply nearly half the water used for irrigated agriculture in the US and provide over 100 million Americans with drinking water. Unfortunately, pervasive pumping is causing groundwater levels to decline in some areas, including much of California’s San Joaquin Valley and Kansas’ High Plains.

We are a water resources engineer with training in water law and a water scientist and large-data analyst. In a recent study, we mapped the locations and depths of wells in 40 countries around the world and found that millions of wells could run dry if groundwater levels decline by only a few meters. While solutions vary from place to place, we believe that what’s most important for protecting wells from running dry is managing groundwater sustainably—especially in nations like the US that use a lot of it.

Groundwater use today

Humans have been digging wells for water for thousands of years. Examples include 7,400-year-old wells in the Czech Republic and Germany, 8,000-year-old wells in the eastern Mediterranean, and 10,000-year-old wells in Cyprus. Today wells supply 40 percent of water used for irrigation worldwide and provide billions of people with drinking water.

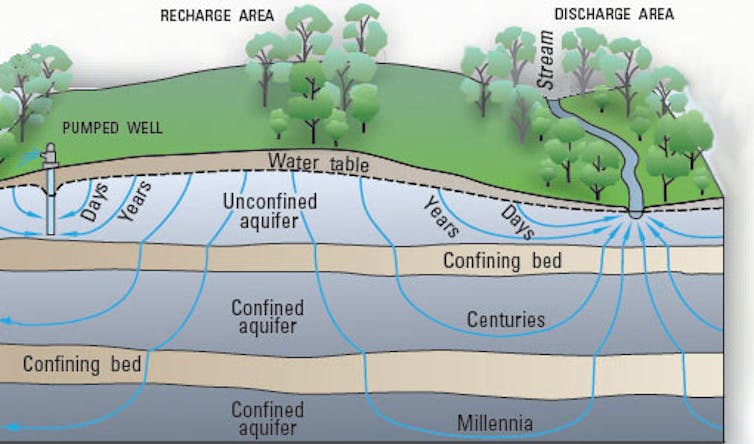

Groundwater flows through tiny spaces within sediments and their underlying bedrock. At some points, called discharge areas, groundwater rises to the surface, moving into lakes, rivers and streams. At other points, known as recharge areas, water percolates deep into the ground, either through precipitation or leakage from rivers, lakes and streams.

Groundwater depletion can also cause wells to run dry when the top surface of the groundwater—known as the water table—drops so far that the well isn’t deep enough to reach it, leaving the well literally high and dry. Yet until recently, little was known about how vulnerable global wells are to running dry because of declining groundwater levels.

There is no global database of wells, so over six years we compiled 134 unique well construction databases spanning 40 different countries. In total, we analyzed nearly 39 million well construction records, including each well’s location, the reason it was constructed and its depth.

Our results show that wells are vital to human livelihoods—and recording well depths helped us see how vulnerable wells are to running dry.

Millions of wells at risk

Our analysis led to two main findings. First, up to 20 percent of wells around the world extend no more than 16 feet (5 meters) below the water table. That means these wells will run dry if groundwater levels decline by just a few feet.

Second, we found that newer wells are not being dug significantly deeper than older wells in some places where groundwater levels are declining. In some areas, such as eastern New Mexico, newer wells are not drilled deeper than older wells because the deeper rock layers are impermeable and contain saline water. New wells are at least as likely to run dry as older wells in these areas.

Wells are already going dry in some locations, including parts of the US West. In previous studies we estimated that as many as 1 in 30 wells were running dry in the western US, and as many as 1 in 5 in some areas in the southern portion of California’s Central Valley.

Households already are running out of well water in the Central Valley and southeastern Arizona. Beyond the Southwest, wells have been running dry in states as diverse as Maine, Illinois and Oregon.

What to do when the well gives out

How can households adapt when their well runs dry? Here are five strategies, all of which have drawbacks.

– Dig a new, deeper well. This is an option only if fresh groundwater exists at deeper depths. In many aquifers deeper groundwater tends to be more saline than shallower groundwater, so deeper drilling is no more than a stopgap solution. And since new wells are expensive, this approach favors wealthier groundwater users and raises equity concerns.

– Sell the property. This is often considered if constructing a new well is unaffordable. Drilling a new household well in the US Southwest can cost tens of thousands of dollars. But selling a property that lacks access to a reliable and convenient water supply can be challenging.

– Divert or haul water from alternative sources, such as nearby rivers or lakes. This approach is feasible only if surface water resources are not already reserved for other users or too far away. Even if nearby surface waters are available, treating their quality to make them safe to drink can be harder than treating well water.

– Reduce water use to slow or stop groundwater level declines. This could mean switching to crops that are less water-intensive, or adopting irrigation systems that reduce water losses. Such approaches may reduce farmers’ profits or require upfront investments in new technologies.

– Limit or abandon activities that require lots of water, such as irrigation. This strategy can be challenging if irrigated land provides higher crop yields than unirrigated land. Recent research suggests that some land in the central US is not suitable for unirrigated “dryland” farming.

Households and communities can take proactive steps to protect wells from running dry. For example, one of us is working closely with Rebecca Nelson of Melbourne Law School in Australia to map groundwater withdrawal permitting—the process of seeking permission to withdraw groundwater—across the US West.

State and local agencies can distribute groundwater permits in ways that help stabilize falling groundwater levels over the long run, or in ways that prioritize certain water users. Enacting and enforcing policies designed to limit groundwater depletion can help protect wells from running dry. While it can be difficult to limit use of a resource as essential as water, we believe that in most cases, simply drilling deeper is not a sustainable path forward.

Debra Perrone is an assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of California Santa Barbara. Scott Jasechko is an assistant professor of water resources at the University of California Santa Barbara.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Debra Perrone and Scott Jasechko, Modern Farmer

May 11, 2021

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreShare With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Many technologies should be used in the development of water wells. This will be a huge expense.