Returning the ‘three sisters’ – corn, beans and squash – to Native American farms nourishes people, land and cultures

Indigenous peoples have grown these companion crops together for centuries.

Returning the ‘three sisters’ – corn, beans and squash – to Native American farms nourishes people, land and cultures

Indigenous peoples have grown these companion crops together for centuries.

Squash, beans and corn make up the three sisters.by Paul B. Moore on Shutterstock

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Historians know that turkey and corn were part of the first Thanksgiving, when Wampanoag peoples shared a harvest meal with the pilgrims of Plymouth plantation in Massachusetts. And traditional Native American farming practices tell us that squash and beans likely were part of that 1621 dinner too.

For centuries before Europeans reached North America, many Native Americans grew these foods together in one plot, along with the less familiar sunflower. They called the plants sisters to reflect how they thrived when they were cultivated together.

Today three-quarters of Native Americans live off of reservations, mainly in urban areas. And nationwide, many Native American communities lack access to healthy food. As a scholar of Indigenous studies focusing on Native relationships with the land, I began to wonder why Native farming practices had declined and what benefits could emerge from bringing them back.

To answer these questions, I am working with agronomist Marshall McDaniel, horticulturalist Ajay Nair, nutritionist Donna Winham and Native gardening projects in Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Our research project, “Reuniting the Three Sisters,” explores what it means to be a responsible caretaker of the land from the perspective of peoples who have been balancing agricultural production with sustainability for hundreds of years.

Abundant harvests

Historically, Native people throughout the Americas bred indigenous plant varieties specific to the growing conditions of their homelands. They selected seeds for many different traits, such as flavor, texture and color.

Native growers knew that planting corn, beans, squash and sunflowers together produced mutual benefits. Corn stalks created a trellis for beans to climb, and beans’ twining vines secured the corn in high winds. They also certainly observed that corn and bean plants growing together tended to be healthier than when raised separately. Today we know the reason: Bacteria living on bean plant roots pull nitrogen – an essential plant nutrient – from the air and convert it to a form that both beans and corn can use.

Squash plants contributed by shading the ground with their broad leaves, preventing weeds from growing and retaining water in the soil. Heritage squash varieties also had spines that discouraged deer and raccoons from visiting the garden for a snack. And sunflowers planted around the edges of the garden created a natural fence, protecting other plants from wind and animals and attracting pollinators.

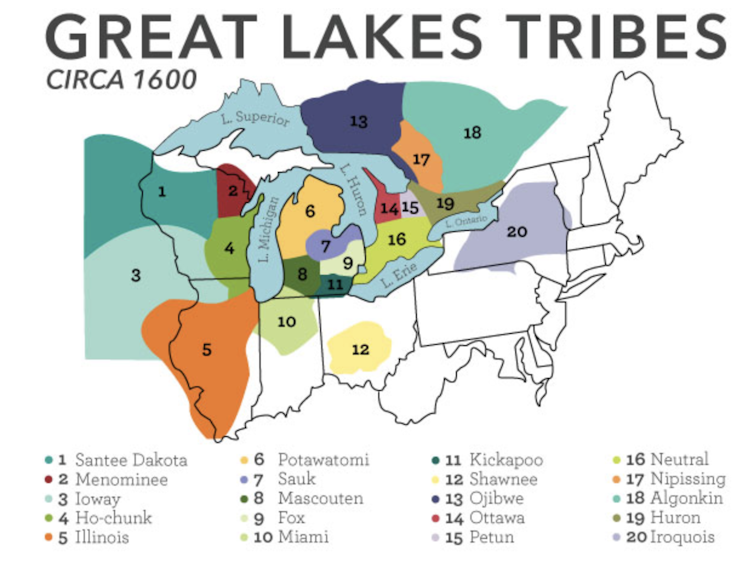

Interplanting these agricultural sisters produced bountiful harvests that sustained large Native communities and spurred fruitful trade economies. The first Europeans who reached the Americas were shocked at the abundant food crops they found. My research is exploring how, 200 years ago, Native American agriculturalists around the Great Lakes and along the Missouri and Red rivers fed fur traders with their diverse vegetable products.

Displaced from the land

As Euro-Americans settled permanently on the most fertile North American lands and acquired seeds that Native growers had carefully bred, they imposed policies that made Native farming practices impossible. In 1830 President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which made it official U.S. policy to force Native peoples from their home locations, pushing them onto subpar lands.

On reservations, U.S. government officials discouraged Native women from cultivating anything larger than small garden plots and pressured Native men to practice Euro-American style monoculture. Allotment policies assigned small plots to nuclear families, further limiting Native Americans’ access to land and preventing them from using communal farming practices.

Native children were forced to attend boarding schools, where they had no opportunity to learn Native agriculture techniques or preservation and preparation of Indigenous foods. Instead they were forced to eat Western foods, turning their palates away from their traditional preferences. Taken together, these policies almost entirely eradicated three sisters agriculture from Native communities in the Midwest by the 1930s.

Reviving Native agriculture

Today Native people all over the U.S. are working diligently to reclaim Indigenous varieties of corn, beans, squash, sunflowers and other crops. This effort is important for many reasons.

Improving Native people’s access to healthy, culturally appropriate foods will help lower rates of diabetes and obesity, which affect Native Americans at disproportionately high rates. Sharing traditional knowledge about agriculture is a way for elders to pass cultural information along to younger generations. Indigenous growing techniques also protect the lands that Native nations now inhabit, and can potentially benefit the wider ecosystems around them.

But Native communities often lack access to resources such as farming equipment, soil testing, fertilizer and pest prevention techniques. This is what inspired Iowa State University’s Three Sisters Gardening Project. We work collaboratively with Native farmers at Tsyunhehkw, a community agriculture program, and the Ohelaku Corn Growers Co-Op on the Oneida reservation in Wisconsin; the Nebraska Indian College, which serves the Omaha and Santee Sioux in Nebraska; and Dream of Wild Health, a nonprofit organization that works to reconnect the Native American community in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, with traditional Native plants and their culinary, medicinal and spiritual uses.

We are growing three sisters research plots at ISU’s Horticulture Farm and in each of these communities. Our project also runs workshops on topics of interests to Native gardeners, encourages local soil health testing and grows rare seeds to rematriate them, or return them to their home communities.

The monocropping industrial agricultural systems that produce much of the U.S. food supply harms the environment, rural communities and human health and safety in many ways. By growing corn, beans and squash in research plots, we are helping to quantify how intercropping benefits both plants and soil.

By documenting limited nutritional offerings at reservation grocery stores, we are demonstrating the need for Indigenous gardens in Native communities. By interviewing Native growers and elders knowledgeable about foodways, we are illuminating how healing Indigenous gardening practices can be for Native communities and people – their bodies, minds and spirits.

Our Native collaborators are benefiting from the project through rematriation of rare seeds grown in ISU plots, workshops on topics they select and the new relationships they are building with Native gardeners across the Midwest. As researchers, we are learning about what it means to work collaboratively and to conduct research that respects protocols our Native collaborators value, such as treating seeds, plants and soil in a culturally appropriate manner. By listening with humility, we are working to build a network where we can all learn from one another.

Christina Gish Hill is an associate professor of anthropology at Iowa State University.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Christina Gish Hill, Modern Farmer

November 26, 2020

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

This works great for the combination of DENT CORN, WINTER SQUASH, and BEANS to be DRIED on the vine. The whole tangled mass of plants is pulled up together at the end of the season. Anybody who tries this with string beans, sweet corn, and summer squash and expects to pick these off and on through the summer is in for a disappointment. Please be specific. Many people try and fail because they don’t understand this.