While Christmas is a ways away, we can still learn a thing or two about patience, stewardship and selling our wares, from this tree farm veteran.

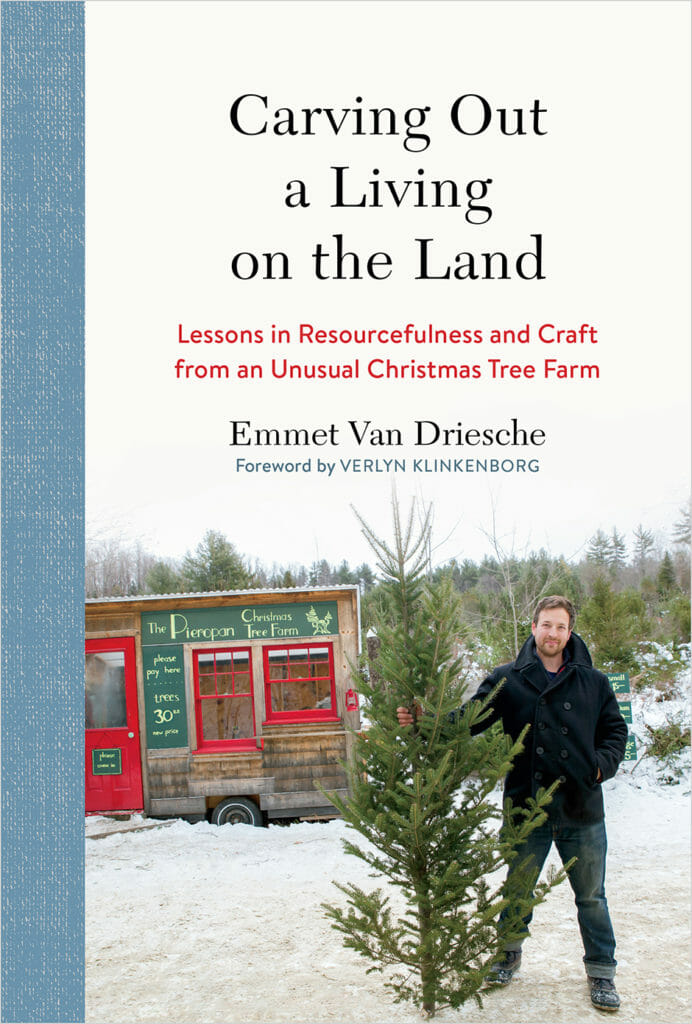

The following excerpt is from Emmet Van Driesche’s new book Carving Out a Living on the Land: Lessons in Resourcefulness and Craft from an Unusual Christmas Tree Farm (Chelsea Green Publishing, June 2019) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

The Art of Selling

Selling, whether in person or online, requires a level of promotion that many farmers are uncomfortable with, and a level of interaction that often runs against the grain for individuals who might be inclined to their own company. The truth, however, is that farming is as much about selling as growing, unless you sell all your crop as a commodity to one buyer. The image of the farmer as taciturn or preferring their own company just doesn’t fit with the successful farmers I know, all of whom are very good at marketing themselves, chatting with customers, and generally being charming and charismatic. If that seems like a high bar, remember that they are not like this all the time. As with most people, they have a limited supply of extroversion, which they recharge by being alone.

I work alone basically every day throughout the year, with the exception of the actual Christmas tree season, and even then I am alone (or with my crew) on weekdays. On weekends, I chat and laugh with customers for eight hours straight, and I come home tired from socializing, even though in the moment it is invigorating and keeps me going. I need the quiet at the beginning and end of the day to balance out the rest, but when I am on, I am on, and if you do direct sales, you need to figure out how to develop this skill, too. People know when you are disengaged, grumpy, impatient, or desperate for a sale. You need to cultivate an easy cheerfulness, not only because this will draw customers to you, but because this is what will keep you happiest in the long run. I don’t fake my sociability, but rather recharge the well by making sure I have time alone.

Remember that selling is about serving someone else’s needs. Make sure that what you are selling is excellent and fairly priced, and people will be drawn to you. It is much more fun to ask people how you can help them than it is to try to convince them to buy. If you are at a farmers market, be willing to act goofy as a means of breaking the ice. Wear a Hawaiian shirt. Wear one of those fake noses with the eyeglasses and mustache. Do some boogie dancing when no one is around. If people come to your farm, make a playlist of songs to set the mood. I listen to all kinds of music when customers aren’t around, but when they are, I find the absolute best kind of music is not Christmas carols (which we’ve all heard too many times before), but a carefully curated list of Motown and soul classics. Put on Stevie Wonder or Aretha Franklin, and watch people start to smile and sing along. Because I don’t have electricity at the grove, I use my phone or an iPod plugged into a portable speaker.

The power of music to set the mood is not a new idea. The original owner of our farm, Al Pieropan, used to park his truck down at the You-Cut grove, open both doors, and tune the radio to classical music. The doors did a good job of projecting the sound up the hillside, and people still reminisce about how lovely it was to trudge through the trees in the snow, opera wafting up from below. Al used this same technique to listen to music while he worked in his sections of the grove in the early years of us taking over the farm, and more than once I had to go jump his truck when he accidentally drained his battery.

As you evaluate your land and your core opportunities, take a moment to think about what level of daily or weekly customer interaction would be a good fit for you. If you love schmoozing, then a farmers market, CSA, or farm store is probably a smart choice. If you would rather not make small talk with strangers, then wholesale might be a better strategy, where you could cultivate a fixed number of relationships and touch base with them as needed. For me, the intense but brief period of social interaction from Thanksgiving to Christmas is balanced out by the rest of the year, when I work alone.

Patience

While Christmas trees and greens represent the obvious core opportunities on our farm, the land does not produce them of uniform quality on all of our 10 acres. Some areas are in good shape; we’ve brought many back to peak production, with each carefully tended stump growing multiple trees as efficiently as possible, and the greens cut back every few years. Other areas are completely overgrown, with full-sized trees that will require a chain saw and a great deal of effort to remove, and that will need to be replanted once that is done. Much of the farm is somewhere in between, with productive stumps intermingled with overgrown clusters of maturing trees. Each year, I try to take down some of these overgrown patches, to convert them back into productive stumps, but it is slow going, and the need for efficiency during the harvesting season means I can only do so much of it each year.

For the truly overgrown sections, I watch and wait. While I could spend a tremendous amount of time cutting these down now, it is not yet clear to me what subsequent course of action would make the most sense. Maybe I could find an economic use for the lumber. Or I might need the additional greens in a couple of years if demand outstrips what the rest of the grove can sustainably produce. There may also be some other economic value to keeping these trees that I cannot see right now. So rather than charge ahead and make big changes before I’m ready, I do nothing.

Doing nothing is one of the most important skills to develop when it comes to land. It is easy to think we know what we need to do, only to realize after a couple of years that we were wrong and should have been doing something else. Particularly with trees, which take years and even decades to grow, change for the worse can happen swiftly, obliterating what took so long to develop; so until I have a plan for an area that is not performing at its peak, I wait. This degree of patience is needed for all of the farm, for it is the task of many years to push back the multiflora rose, to open up trails that have been neglected, to fill in muddy sections of trail with wood chips, and to tackle stumps that have become overgrown. I cannot do it all in one year. Bringing this farm up to speed will be a twenty-year process, in which I am only halfway.

The same is true for any farm, existing or envisioned. Land stewardship is a long-term habit, and one whose full potential cannot be realized in a shorter time frame. Good land, healthy land, land that is fertile and productive and humming along takes years and years to get that way. If you are lucky enough to stumble upon it, or have enough money to buy such a thing, recognize that someone else made good decisions for a long time before you came along. Don’t mess it up.

If you own or can only afford to buy land that has been neglected, recognize what you are walking into. Be realistic in your expectations. Be realistic about the cost, in time and money and sweat (and don’t fool yourself that you can get away with time and sweat alone, because it will definitely take money in the end), that rehabilitating the land will require. It will be worth it. If the farm is near a good market, or has other valuable attributes (a good house, or a beautiful natural landscape, or excellent neighbors, or just that it’s available), then go for it. But pace yourself. Don’t plow up more than you can properly manage. Come up with a realistic five-year plan for liming the pasture, or clearing the thickets, or remineralizing the fields, and then stick to it.

Some people can tolerate turning everything on its head, giving it a good shake, and then living in the chaos while it slowly improves. Renovating a house while living in it is a good example of this. I am not so able to tolerate such a state of affairs, preferring instead to keep things as pleasant as possible while making incremental changes. Partly this is skepticism that my first idea will ultimately be my best one, but it’s also because I believe in maintenance, in small improvements that add up over time. Whether a car, a house, or a farm, I believe that doing what you can in the moment is better than saving up for some big overhaul in the future.