Now, he is working on a full-fledged Native American restaurant slated for 2019 in Minneapolis and the North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems

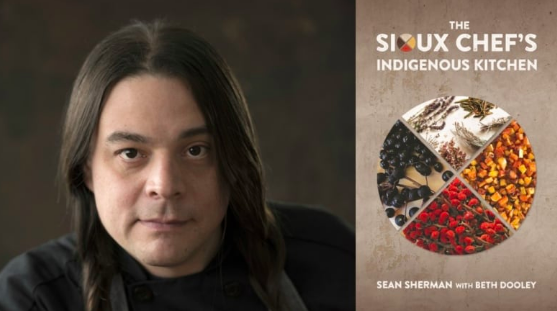

In 2014, the enterprising chef launched Sioux Chef (sioux-chef.com), a mini culinary empire founded on the idea of digging up and popularizing pre-contact foods. Now, he is working on a full-fledged Native American restaurant slated for 2019 in Minneapolis and the North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS), a non-profit incubator raising up food heroes in tribal communities.

He’s at the forefront of the indigenous food movement: Sherman co-launched the Sioux Chef with his partner Dana Thompson as a catering company. Soon after, came the food trucks, a Kickstarter restaurant project (the most-funded restaurant on the platform), educational workshops, speaking gigs, and the book. Last year, the duo banded with other chefs, ethnobotanists, food preservationists, and artists, across the nation to fuel NAFTIS, which aims to increase access to and knowledge of pre-contact foods. “No matter where you are in North America, there’s indigenous history, culture, and food there,” he says. “We just want people to realize that.”

He uses food to fight disease: A member of the Oglala Lakota tribe in South Dakota, Sherman witnessed how an over-reliance on government-funded, sugar-and salt-laden commodity foods, led to disproportionately high rates of diabetes and kidney disease within reservations. He aims to buck the trend by championing pre-colonial foods, which are mostly absent of dairy, wheat flour, cane sugar, beef, pork, and chicken. “Teaching people that it’s cool to reclaim cultural foods is going to be way more effective than telling people just to eat healthy,” he says. “There’s a sense of pride that comes with eating our own foods.”

He doesn’t follow a one-size-fits-all approach: NAFTIS helps tribes build community-specific farms, production facilities, and restaurants by any means necessary (grant writing assistance, fundraising, technical training). “Each business will be unique. It will represent the particular land, history, culture, people, and stories of the area,” he says. At the heart of the organization is a series of Indigenous Food Hubs (complete with a restaurant and an educational facility) which will be planted in urban areas. From there, the group can help build out other businesses – from farms to eateries – within tribal communities near the city. “We believe in redesigning the landscape to put food everywhere,” he says.

Sean Sherman winnows wild rice in the breeze so that the last of the chaff blows away. Then it’s ready to be cooked and enjoyed. / Photo by Nancy Bundt

He crosses borders: “We don’t only want to affect the U.S., but also Canada and Central America,” he says. Sherman designed the program with scale in mind, drawing from his experience with the restaurant franchise model. “You have the hub where all the calls are made, then utilize a lot of specialists – resources and people on the ground – to build satellite teams,” he says.

He wants to change the story: For his cookbook, which hit shelves late last year, Sherman interviewed dozens of elders from different tribes. “There’s a colonial mindset of ignoring the past, but I think it’s important for anyone, native or otherwise, to understand that there’s a much deeper history across North America,” he says. “Aside from the tragedy, there are generations of knowledge that are extremely valuable – especially compared to, you know, 150 years of colonial knowledge.”