Plants Need a Little Vigor? How to Choose a Good Fertilizer

Think of them as vitamins for plants.

In an ideal world, we would grow food in a way that does not deplete the soil, thereby eliminating the need for boosting nutrient levels with fertilizer. We would also choose crops based on what our particular soil type – which might be higher in some nutrients and lower in others – is best suited for. And of course there are many biological methods to improve nutrient availability in the soil, from simply adding compost to growing cover crops, which are the backbone of any holistic approach to fertility management. The old adage that real farmers grow soil, not crops, is more important than ever in the age of high-input chemical agriculture.

But the world is not an ideal place, and most farmers and gardeners are reliant on fertilizers beyond just compost, which are more accurately described as a soil amendments. In the name of demystifying the marketing hype and technical jargon, here are a few tips to help you sniff out the products best suited to your unique horticultural circumstances, with as little negative environmental side effects or health hazards as possible.

Organic, All-Natural, or Synthetic?

First question: How do you tell what’s synthetic and what’s not? That’s fairly straightforward – usually. The ingredients in each fertilizer product should be listed on the container. Organic products contain natural substances like blood and bone meal, cottonseed meal, fish meal, rock dust, kelp, etc. On the contrary, if you see ingredients like “ammoniated super-phosphate” or “isobutylidene diurea,” you’re looking at a synthetic product.

The distinction is less clear with some terms, however. Phosphates are generally associated with synthetic fertilizers, but some organic fertilizer products may also list phosphates as an ingredient – if you see the term listed by itself or as “rock phosphate,” a naturally occurring mineral, it is generally an organic product, while most other forms of phosphate (products like diammonium phosphate and polyphosphate, for example) are synthetics.

“Urea,” a common source of nitrogen used by fertilizer manufacturers, is another confusing term. While it can be derived from animal urine, a natural source, the urea listed in fertilizer is almost always a synthetic form made from natural gas. Because it is a carbon-based compound, it can legally be described as an organic fertilizer (even if the urea is synthetic), and often is, though this is a highly misleading claim.

Natural vs Organic: Understanding Labels

This brings about an important point about fertilizer labels: “organic” does not mean the same thing in the fertilizer aisle as at the grocery store. There is no such thing as organic certification for fertilizers, so the word is often used in the broadest sense, meaning simply “carbon-based.” This is why it’s good to check the ingredients. The term “natural” is more relevant than “organic” on fertilizers – which is pretty much the opposite of food – as it indicates that the ingredients are derived from minimally processed (i.e. ground up and mixed with other natural substances that make them easier to apply or more effective in some way) plant, animal, or mineral sources, rather than artificially synthesized. The Organic Materials Review Institute maintains a list of fertilizers that are compatible with organic growing practices; look for the OMRI seal to be sure a product is not using the word “organic” in a misleading way.

The Ugly Truth About Synthetic Fertilizers

Why does it matter if fertilizer is natural or synthetic? As far as the plants are concerned there’s not much difference – a molecule of nitrogen is the same, whether it’s derived through natural or synthetic means. The biggest difference for plants is that synthetic fertilizers are usually in a form that’s easy to absorb, so they get a quick boost of the nutrient rather than a slow release.

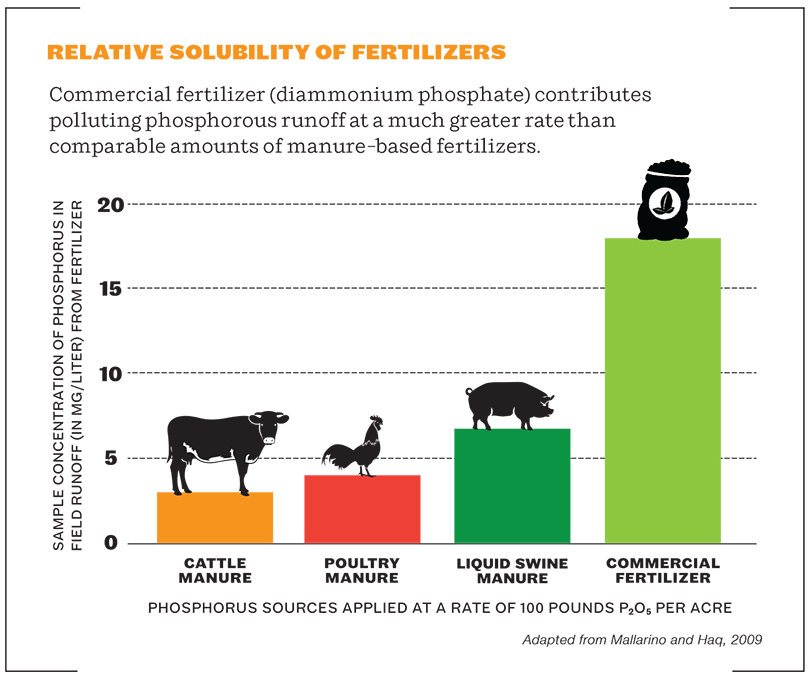

But there are drawbacks. Synthetic nutrients do not feed the soil food web, which means biological life in the soil slowly ceases to function as it should, a process that is accelerated by the relatively high salts and acidity of chemical fertilizers. The result is powdery, crusted over, nearly lifeless soil, and thus greater dependency on fertilizers to provide nutrients, rather than biological processes. Plus, synthetic nutrients are highly water soluble and tend to run off into the watershed, where they cause toxic algae blooms and other environmental havoc. Not to mention that they require huge quantities of fossil fuels to produce and even contribute to greenhouse gases after they are applied – a double whammy on a warming planet.

The Limits of Natural Fertilizers

Synthetic fertilizers are seductive because they are often cheaper than the all-natural alternatives and provide a greater concentration of nutrients in a short time frame. Natural fertilizers are noticeably less effective at promoting growth in early spring when the soil is cold – they rely on microbial activity to make the nutrients available, but there is relatively little microbial activity until nighttime temperatures stay consistently above 50 degrees. Because of this inherent limitation, USDA organic standards allow for the use of some synthetic fertilizers in early spring so farmers can get their crops going early in the season and remain competitive with conventional growers.

Just because a fertilizer is made from natural substances, doesn’t mean it can’t cause harm if used inappropriately.

Also, just because a fertilizer is made from natural substances, doesn’t mean it can’t cause harm if used inappropriately. Over-fertilizing a crop with more nutrients than it can absorb, whether synthetic or natural, means those nutrients will eventually end up in groundwater or a surface waterway nearby, where they become a form of pollution rather than an asset. The high solubility of synthetic nutrients makes it easier for this to occur, but it can happen with manures and other natural nutrient sources too, especially if they are applied on the surface of the soil just before a big rainstorm. And while most natural nutrient sources are non-toxic to people, pets and wildlife, a select few – mainly micronutrients such as copper – are potentially toxic if consumed, and must be applied in accordance with the safety instructions on the label.

N-P-K: Fertilizer’s Holy Trinity

Perplexed by those three cryptic numbers you see on the front of nearly every bag of fertilizer? They represent the percentage of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in the product, often abbreviated as N-P-K. These are the three most essential plant nutrients; nitrogen is the most commonly deficient of the three, though the latter two are a limiting factor to plant growth in some soils.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen is responsible for green vegetative growth and is most important in spring and early summer. If your garden lacks overall vigor and leaves have a pale yellow-green cast, use a fertilizer rich in nitrogen to encourage deep green verdant growth.

But be sure to follow the recommended application rates as over-fertilizing with nitrogen can “burn” the leaves, leaving them brown around the edges and stunted. Excess nitrogen makes plant tissues extra juicy and succulent, and less resistant to insect pests that come to feed on them. The tender new growth promoted by nitrogen fertilizer is also more susceptible to frost damage, so don’t use it too early or late in the season.

Common organic sources of nitrogen include blood meal, fish emulsion, and animal manures.

Phosphorus and Potassium

Phosphorus and potassium play a variety of roles in plant physiology, including disease resistance, root growth, and the formation of flowers, fruits, and seeds. Fertilizers that claim to boost flower, fruit, or root growth are typically high in phosphorus, though it’s really their lack of nitrogen that is responsible for this effect – excess nitrogen promotes vegetative growth at the expense of these other critical functions, yet another reason to use it in moderation.

Common organic sources of phosphorus include bat guano, rock phosphate, and bone meal. Common organic sources of potassium, which is often listed as “potash,” include wood ash and greensand, a marine mineral deposit.

Start with a Soil Test

A soil test is the best way to identify which N-P-K ratio is needed to address nutrient deficiencies in your soil. Otherwise you risk putting down excess fertilizer that plants can’t absorb, which may then end up in groundwater or nearby rivers and streams (this can occur with all-natural fertilizers, as well as synthetics). Basic soil tests are available for a small fee through your local cooperative extension service office, though private labs offer a more comprehensive analysis.

The soil test results tell you how many pounds of each nutrient is needed. You can then convert those numbers to actual pounds of fertilizer using the N-P-K percentages. For example, a ten-pound bag of fertilizer marked 10-5-5 has one pound of pure nitrogen and a half pound each of phosphorus and potassium. So if the soil test calls for .25 pounds of nitrogen per 1,000 square feet, that ten-pound bag would be enough for four applications on a garden of that size.

A soil test will also tell you if your soil is deficient in any of micronutrients that are essential plant health, or if the pH is particularly high or low.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Brian Barth, Modern Farmer

June 28, 2016

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Before reading this article, I didn’t know that natural plant fertilizers solutions for sale were so different from synthetic. It is interesting that natural fertilizer is usually better than organic fertilizer. I’ll have to look for this in the spring when preparing the soil.