What’s Old Is New Again: Chefs Rediscover Schmaltz

The magic of an old Jewish workaround to Kosher laws finds favor among younger chefs.

What’s Old Is New Again: Chefs Rediscover Schmaltz

The magic of an old Jewish workaround to Kosher laws finds favor among younger chefs.

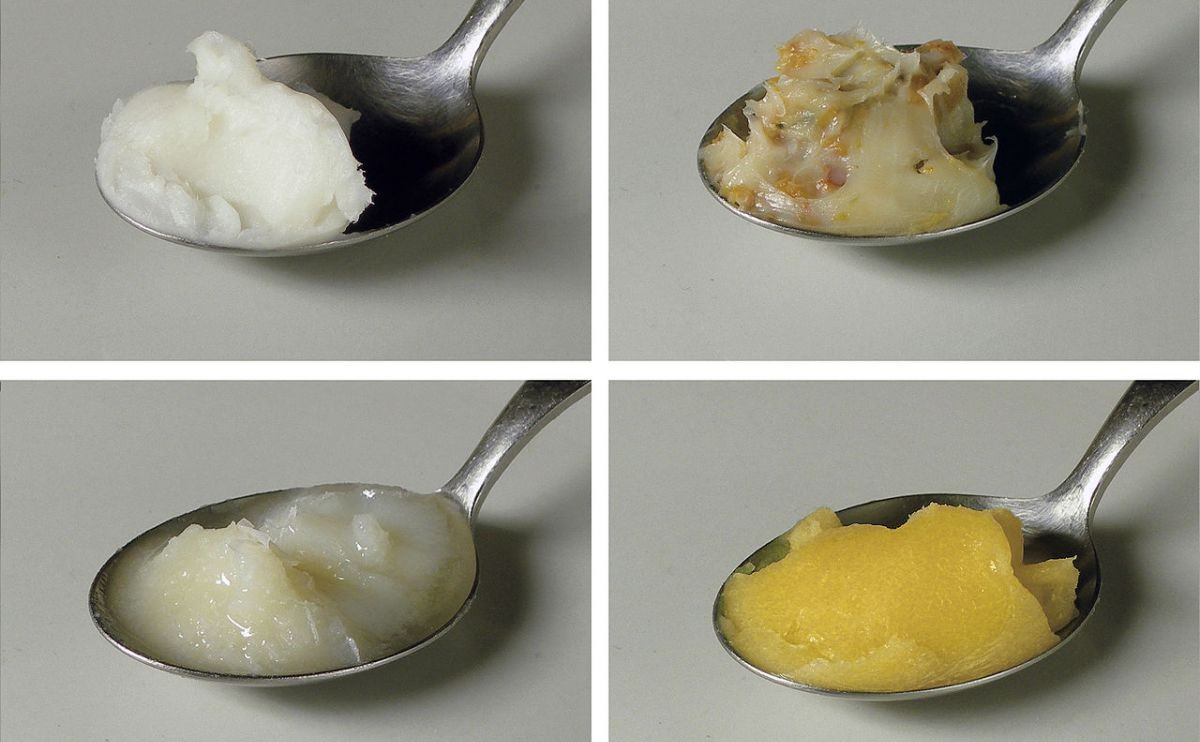

So let’s first discuss what schmaltz actually is: It’s essentially, chicken fat, typically made by simply cooking chunks of skin-on, bone-in chicken, and usually some chopped onion, in a pan over low heat for a fairly long amount of time. The heat turns the chicken fat from solid to liquid, and it eventually melts out of the chicken and into the pan, a process called “rendering.” This also leaves some crisp chicken skin in the pan, which in Yiddish are a delicacy known as gribenes. (You’ve done this before; putting a strip of bacon in a pan and crisping it is the exact same process. And in fact, gribenes is sometimes known as “Jewish bacon.”)

Though schmaltz can be made with goose and duck fat, in the United States, where goose and duck are not nearly as commonly eaten, schmaltz is almost exclusively made with chicken. The process is one of many techniques Jews have developed for working around the rules of Kashrut, or Kosher; eating Kosher is like a life-long Top Chef challenge.

Most varieties of fat are either non-Kosher or weren’t affordable in much of the Eastern European Jewish community. Lard, made of pork fat, is, obviously, not Kosher. Butter, though definitely a part of Jewish cuisine, can’t be used to cook meat, due to the ban on the combination of dairy and meat. Most cheap varieties of beef fat, like suet, are not Kosher, due to a prohibition on fats known as chelev, referring to a specific kind of animal fat. (The rules about chelev are sort of arcane and complicated, but basically prohibit animal fats taken from around organs, which would include suet.) Jews in the United States now usually opt for relatively inexpensive vegetable or olive oils (or, weirdly, Crisco, which is hugely popular), but these oils were prohibitively expensive in Eastern Europe before around the 1950s.

So Jews were left to figure out some kind of workaround, something that isn’t pork, isn’t dairy, isn’t expensive, and isn’t chelev. The solution to this problem ended up being schmaltz.

And, luckily, it turns out schmaltz is incredibly delicious. Jews have long used it to cook meats, but because it’s so tasty, it’s used as an all-purpose fat. It’s used to fry potato latkes, in place of oil. It’s salted and spread on bread, in place of butter. A small pitcher graces every table at New York’s justifiably famous Sammy’s Roumanian Steakhouse, a traditional, out-of-time Ashkenazic restaurant. But over the past few years, it’s also been popping up in trendier, often not-at-all-Jewish establishments.

At Ivan Ramen, the New York outpost of the Tokyo ramen shop run by expat New Yorker Ivan Orkin, schmaltz is a key ingredient in the base for his shio ramen. Chef David Santos, who operates a Nashville-style hot chicken pop-up, says, “Traditional hot chicken sauce is made with pork fat. I chose chicken fat, a.k.a. schmaltz, because its melting point is lower so it coats my hot chicken better, especially as it cools. Now I love pork fat but for this application, chicken fat for the sauce just gives the dish a better mouth feel.”

Chef Kevin Adey of Brooklyn’s Faro combines schmaltz and gribenes for something very old yet very new. “Schmaltz is awesome – I often finish dishes with it,” he says. “I caramelize chicken skin, puree it with the rendered chicken fat, and use it to finish items like white asparagus and scallops, even cauliflower and dark leafy greens.”

Who knew that an old Jewish technique would find favor in everything from Japanese to Southern to new American food?

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Dan Nosowitz, Modern Farmer

March 17, 2016

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Chicken was also relatively expensive even in the US before the 1920s and industrial farming of chickens.

Ducks and geese were used in Europe because of the large amount of fat available on a goose and then feathers were used for pillows covers etc. with chickens the amount of fat per slaughter is negligible This is why duck and goose fat were more common in central and Eastern European Jewish homes