Capons: Are Chickens Without Their Testes a Forgotten Delicacy or Disturbing Luxury?

How is it that the capon has been left behind even as consumers demand a greater range of choice?

Capons: Are Chickens Without Their Testes a Forgotten Delicacy or Disturbing Luxury?

How is it that the capon has been left behind even as consumers demand a greater range of choice?

Capons fetched four times the price per pound of a typical chicken, he wrote. They had value before slaughter, too: Capons would mother chicks better than hens while still retaining enough of a rooster’s fierceness to fight off hawks. If only farmers had the patience to learn “caponizing,” this particular form of castration, and let the birds grow long enough to develop their tender, distinctive flavor, capons would become “the life-giving, brain-forming, strength-producing food that is required by the high strung workingman of modern times,” Beuoy wrote.

Obviously, he was wrong.

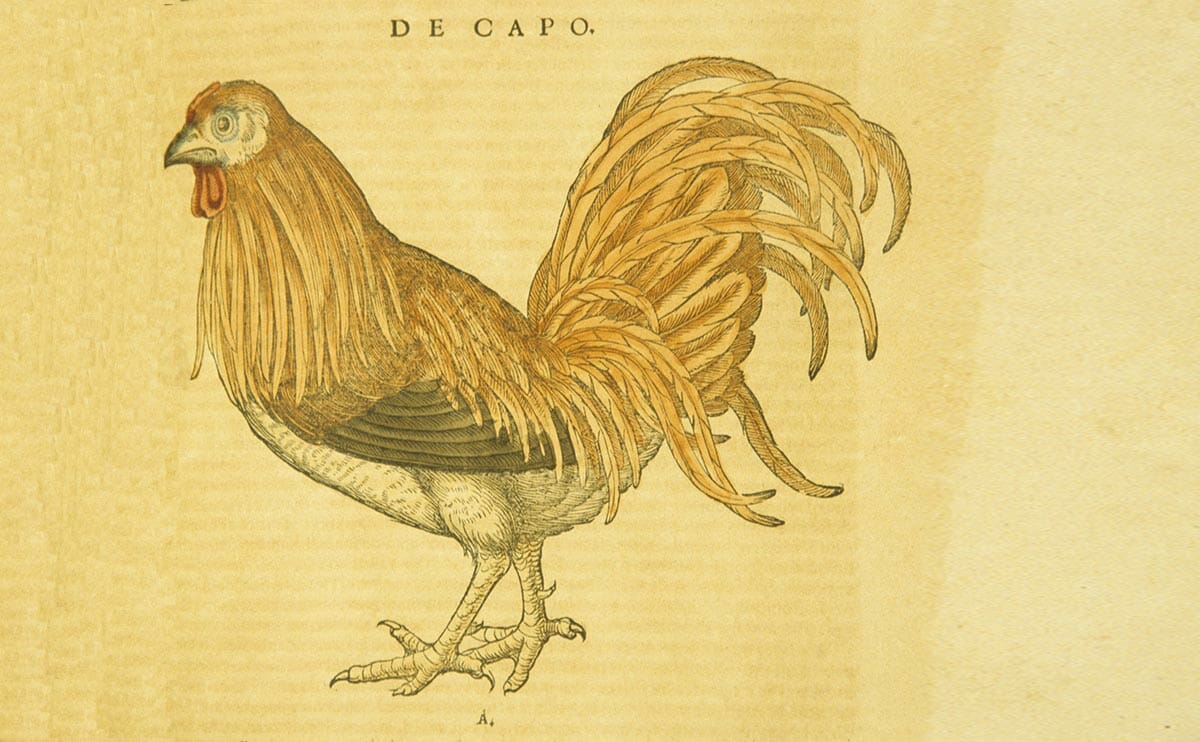

Today, the capon has nearly disappeared from view. When capons pop up in stores or on restaurant menus, most modern diners assume that they’re game birds or perhaps akin to Cornish hens. But because hormonal changes caused by caponization allow more fat to build up both below the skin and within muscle, capons come with the promise of a substantial amount of buttery, tender meat. So why are they gone?

It comes down to fact that the method to make a capon a capon is still the same as it was when Beuoys wrote ”a process that may be an unfairly forgotten piece of agriculture, or simply a means to a somewhat disturbing luxury good.”

The caponizer searches for the testes, each about the size of a grain of rice, and rips them free of their connective tissue with a small slotted spoon–or, in some cases, a tool made out of a loop of horse hair.

Bill Keough spent 20 years caponizing cockerels for Iowa’s Wapsie Produce, which dominated capon production before ceasing operations in 2010. To make a cockerel a capon, he explains, a caponizer must restrain the 3 to 6 week old bird by tying weights to its wings and feet to prevent movement and expose the rib cage. Then the caponizer cuts between the lowest two ribs of the bird and spreads them apart with a special tool to open up access to the body cavity. Last, the caponizer searches for the testes, each about the size of a grain of rice, and rips them free of their connective tissue with a small slotted spoon–or, in some cases, a tool made out of a loop of horse hair.

This is the most difficult part: The testes are delicate, and it’s easy to only partially remove them, allowing some production of the male hormones that will result in a useless animal known as a “split” — not a rooster, not yet a capon. The testes are also next to a crucial artery and the kidneys, and damaging either could kill the bird. The incision is not sutured, and the entire process is done without anesthetics or antibiotics (though it should be said that neither anesthetics or antibiotics are used the more routine castration of cattle or pigs).

When asked, Keough shrugs off concerns that the process could be done more safely or humanely. “There’s not any other way to do it, and I don’t think there should be,” he says. “If you do it right, it only takes a few seconds and the bird doesn’t know what hit him.”

By the time Keough mastered the process as a teenager, he could caponize 300 birds an hour. But to get it right? It took him two or three thousand attempts, he says. “There were plenty of dead chickens laying around,” he remembers. In other words, farming capons depends upon a highly-trained, well-paid specialists — not the sort of assembly-line labor and mechanization on which the modern poultry industry runs. When Keough graduated from high school in the 1960’s, he could charge $75 an hour for his services, he says. “If I did it now, I might get rich,” he adds, wistfully. “But I spent it all. Girls… ”

Even once the flocks have been caponized, they still present challenges to the contemporary farmer. Jim Schiltz, who owns specialty poultry processor Schiltz Foods, struggles to get his suppliers to meet even the modest demand for capons. FDA inspectors maintain extremely strict standards for what can be sold as a capon, and for flocks to make the grade, “you need to give them a little TLC. You need to give them a space. You need to feed them slow,” says Schiltz. If a bird isn’t certified as a true capon, it can only be sold as one of those mammoth roasters that don’t fetch a high enough price to justify raising the bird for 17 weeks (conventional chickens are often slaughtered after as few as four weeks).

“You need to give them a little TLC. You need to give them a space. You need to feed them slow.”

Schiltz says he’s often at loggerheads with farmers–many don’t bother to fill his orders, exasperated with the level of care required, while others cut corners, raising flocks where only half the birds can be sold as capons. “They’re crap, y’know. I don’t even want them, hardly,” he says, sighing. “There’s an art to doing this.”

Schiltz could take the time to whip his farmers into shape, train more caponizers (he says he knows only six people up to that task) and modernize the process if there was stronger demand for the birds. But it’s always been a niche product, and the market has only shrunk. Wapsie at its peak processed 500,000 capons per year, and Schiltz estimates his annual capon production is a tenth of that. In contrast, American farms routinely produce more than 8 billion chickens each year.

How is it that the capon has been left behind even as consumers demand a greater range of choice? Founder of specialty food brand D’artagnan Ariane Daguin believes it’s a question of demographics. A hundred years ago, when Beuoy prophesied a capon in every pot, American families averaged around five members, and so a seven to twelve pound bird was a reasonable size for a family meal. Now the average family has fewer than three members. So, says Daguin, “the capon is becoming obsolete.”

She, like Schiltz, simply tries to service a lingering demand: D’artagnan sells fewer than 2,000 of its $89 French-style capons, fed milk and bread instead of grain, to the small number of European expatriates who don’t traditionally eat turkey at holidays.

I brined and roasted one of Jim Schiltz’s 7.5 pound capons according to a simple recipe by Gabrielle Hamilton of New York City’s Prune restaurant, and the first taste was a revelation. The flavor was unusually rich and complex, distinct from any chicken or turkey I’d had before, and the texture both moist and firm. After years of bland chickens and dried-out holiday turkeys, a taste of capon made me wish George Beuoy’s vision of the Capon of Tomorrow had come to pass.

But developing a mass market for capons would require a Herculean marketing effort the producers currently show no inclination to undertake. And without that public awareness, it’s unlikely the same level of feel-good publicity that makes humanely raised chicken a supermarket staple will come to bear on the caponization process.

With the limited prospects for their products, many capon producers don’t bother touting the jaw-dropping taste of their birds. In the words of Jim Schiltz: “It’s just a chicken with its nuts cut off.”

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Alex Yablon, Modern Farmer

April 11, 2014

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

How odd. If my mother had only known. Growing up her family raised capons and she would tell stories of how she, a small girl at the time, caponized chickens and how much she hated reaching in the cavity and searching for the testes. If she knew she could have made $75 an hour doing it therefore providing a better life for her children as we grew up, she would have been shocked.

At least with cattle and swine, the testes are located externally! You do not need to breach the body wall to castrate them.

My husband and I love capon and have it at least once every six weeks. There is only one store in San Diego county that carries it. We, also, can not understand why more people do not try it.

It’s not any more inhuman than raising your chicks, and than when it’s time to butcher them. Just grab them by their necks a wring it, than step on its head and pull its head off. Watch it flop around slinging blood everywhere. Rabbits whack them in the head than skin them. If your from the country there are a lot of what we might think is gross now. But that was our food supply.

Capons are AWESOME eating a real treat just as goose or duck is a real treat

youtube has the whole caponization process being done in asia some where

Discussing this with a friend, he says the testes are located under the wing. Could you be more precise perhaps with diagram where and how this procedure is accomplished. Thank you for your time.

[…] “Capons: Are Chickens Without Their Testes a Forgotten Delicacy or Disturbing Luxury?” (APR 11, 2014) https://modernfarmer.com/2014/04/capons-unfairly-forgotten-piece-agriculture-somewhat-disturbing-lux… […]

There are several places in your article where what might be an M-dash “—” is actually a pair of inside-out fancy quotes, like this: ”“

Fascinating read! I had no idea capons held such a unique place in agricultural history. Your exploration of their role as both a forgotten practice and a luxury product is eye-opening. While I understand the ethical concerns, it’s intriguing to see how this tradition reflects the intersection of culture, gastronomy, and farming.