The Benefits of Dry-Farming Wine”For the Palate and the Planet

Two Oregon winemakers hope to convince their grape-growing counterparts to resist irrigation.

The Benefits of Dry-Farming Wine”For the Palate and the Planet

Two Oregon winemakers hope to convince their grape-growing counterparts to resist irrigation.

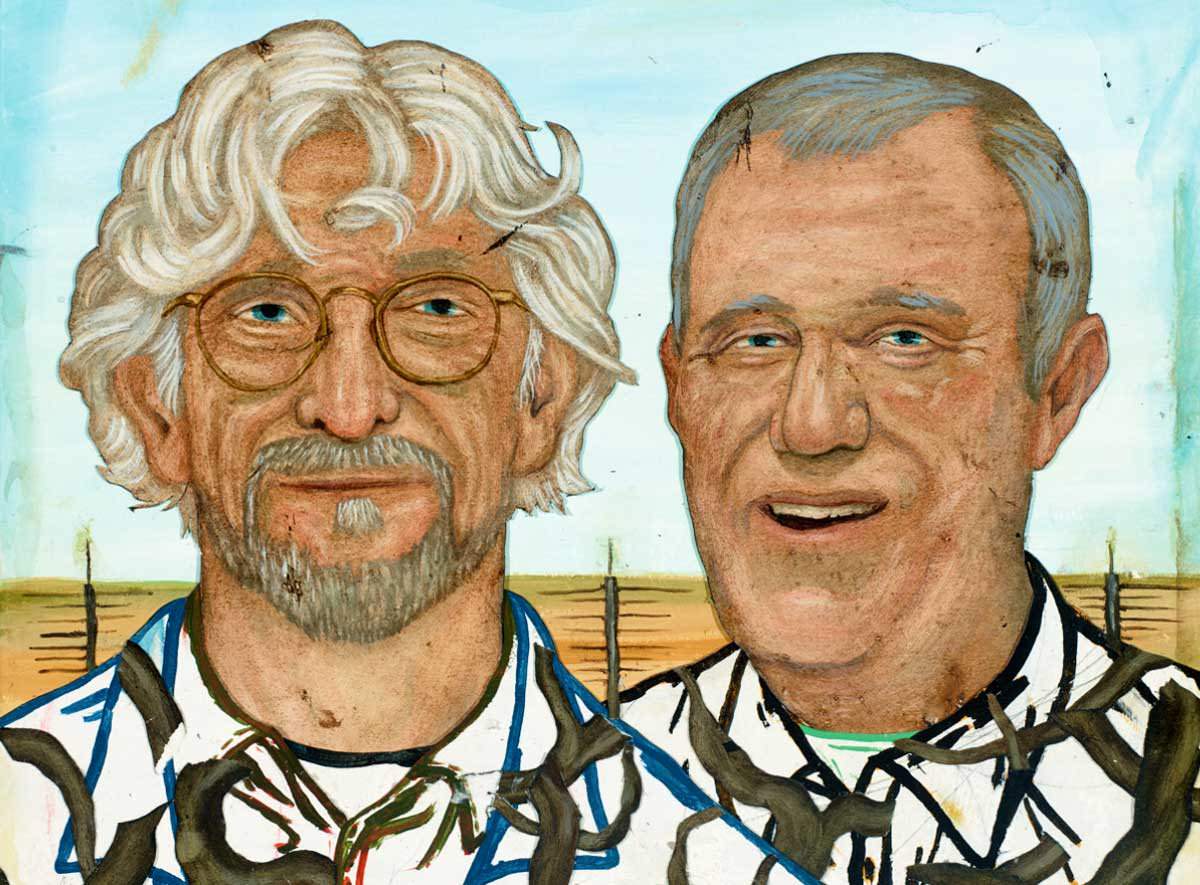

Paul, who owns Cameron Winery, and Raney, the founder of nearby Evesham Wood, practice what’s known as dry farming – they rely on natural precipitation alone for their vines. By 2004, the two had become so troubled by the ongoing irrigation trend that they founded the Deep Roots Coalition to challenge it. (The roots of nonirrigated vines tend to sink deeper into the soil in search of moisture and minerals.) Environmental concerns were a motivating factor, one made more prescient by the fact that more than half of Oregon’s counties are currently under a state of drought emergency. But the primary reason Paul and Raney began promoting dry farming came down to matters of taste. They wanted to encourage others to create complex wines that reflect the soil from which they come.

Growing wine grapes without irrigation is less radical than you might think. France, Italy, Germany, and Spain have been dry farming for centuries. The European wine industry doesn’t just frown upon the supplementation of rainfall; it forbids the practice (with a few exceptions; most European countries permit irrigation for newly planted vines, and some have begun loosening regulations in the case of drought). Water mature vines in France, for instance, and you may find your appellation d’origine contrÁ´lée, the industry’s all-important certification of place, revoked. Adding unnatural quantities of water, the thinking goes, means meddling with a wine’s terroir, its unique expression of place. Even in California, grape growers relied on rain alone until the 1970s, when drip irrigation was introduced to the state. The grapes responsible for establishing Napa Valley as a world-class wine region in the middle of that decade – from brands like Stags’ Leap and Chateau Montelena – all came from dry-farmed vineyards.

Growing wine grapes without irrigation is less radical than you might think. France, Italy, Germany, and Spain have been dry farming for centuries.

Over the years, however, commerce eclipsed custom. Irrigating vines, American farmers found, invariably increased yields. And more grapes per acre meant more profits per acre. (Once the connection with yield had been established, many U.S. banks began refusing loans to vineyards that didn’t promise to irrigate.) Today, the majority of California wineries irrigate their vineyards even in years, and areas, with plentiful rainfall.

Paul and Raney believe that irrigation has a profound impact on flavor. “If you give a vine a bunch of water,” says Paul, who did post-doctoral work in plant physiology, “it gets more stomata on the bottom of the leaves. The result is fruit that tends to have more sugar.” This is why, he explains, the alcohol levels in wine have climbed steadily over the past 30 years. Today, most Oregon wines clock in at 14 percent alcohol or higher. (Paul’s wines average about 12.5.) Not incidentally, those richer, riper, high-alcohol wines are beloved by Robert Parker and other influential wine critics. “Essentially, the character of Napa wines has changed to accommodate irrigated grapes,” says John Williams, the winemaker at Frog’s Leap Vineyard, in Rutherford, California. “The Brix [sugar level] used to be 22 to 23,” adds Williams, who has been dry farming since 1989. “Suddenly it became 24, 25, 26. Many people like that style,” he adds, “including the major wine critics. But to me, they’re undrinkable.”

“If you go to a Deep Roots Coalition tasting,” says Tyson Crowley, the Willamette winemaker who serves as president of the organization, “all the wines taste different. The best wines come out of that dry-farming paradigm, because people aren’t altering the grapes’ basic nature. You get amazing expression, where a vintage stands out and the soil stands out and the site stands out.”

But recognizing the merits of dry farming and actually practicing it are two different things. Farmers can’t simply turn off the tap overnight. Location matters, as do soil and root-stock. When California’s wine industry first became established, for instance, most of the state was planted with two drought-resistant grape varieties. In the mid-’90s, after an epidemic of the microscopic pest phylloxera devastated vineyards in the northern part of the state, many winemakers replanted with a phylloxera-resistant riparian root-stock, which requires a lot of water.

“It’s terrible for dry farming,” says Steve Matthiasson, a Napa winemaker who in 2006 planted his vineyard with just such stock. “I would totally do things differently if I had it to do over again.” Matthiasson is dedicated to sustainability – he farms organically and follows a no-till regime to prevent erosion and sequester carbon. But tearing everything up with a tractor and replacing his current rootstock with a drought-tolerant type, he says, would be anything but earth-friendly. “Talk about carbon footprint!”

The ongoing drought in the nation’s west is serving as a different sort of evangelist: Water-restriction laws are pushing winemakers to farm drier whether they want to or not.

Instead, Matthiasson practices “regulated-deficit irrigation.” He uses a probe to measure the moisture in his fields and irrigates only if absolutely necessary. When he does turn on the water, he keeps it going a full 24 hours, so it penetrates all the way down to the roots. Yet the winemaker says his yield remains the same: around five tons per acre on an average of just 7,200 gallons of water. “Wine grapes grow all over the world with less rain than we’ve gotten this year,” says Williams of Frog’s Leap. (See “Turning Water into Wine,” below.) For his Napa vineyard, Williams chose rootstock well-suited to dry farming, including ‘St. George,’ which tolerates both phylloxera and drought. Though ‘St. George’ is known for low yields, Williams reaps 4 to 4.5 tons of grapes per acre.

As concerns over climate change increase, more winemakers are looking into the merits of dry farming grapes. Today the Deep Roots Coalition counts 26 winemaking brands among its members, and the group regularly hosts dinners, tastings, and other events as a way to educate their peers and the public. Meanwhile, the ongoing drought in the nation’s west is serving as a different sort of evangelist: Water-restriction laws in places like southern Napa are pushing winemakers to farm drier whether they want to or not. As with grazing cattle and farming organically, it seems that when it comes to wine-making, what’s old is new all over again.

Turning Water Into Wine

Just how much water does it take to produce quality wine? Opinions vary. Spain’s La Rioja province, for instance, has historically received an average of only 16 inches of rain a year. And as in other Old World wine regions – Bordeaux and Tuscany included – irrigation of vineyards older than a few years is prohibited (with special dispensations in cases of extreme drought). Though New World wine regions receive more rain (even amid today’s drought, California’s Napa Valley registered 20.7 inches by press time), most American vineyards irrigate nonetheless. Sources: United States – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, based on 30-year averages; Europe – World Meteorological Organization, based on 30- and 50-year averages.

Hannah Wallace is a Portland-based writer who contributes to Vogue, Civil Eats, and Portland Monthly.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Hannah Wallace, Modern Farmer

December 21, 2015

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.