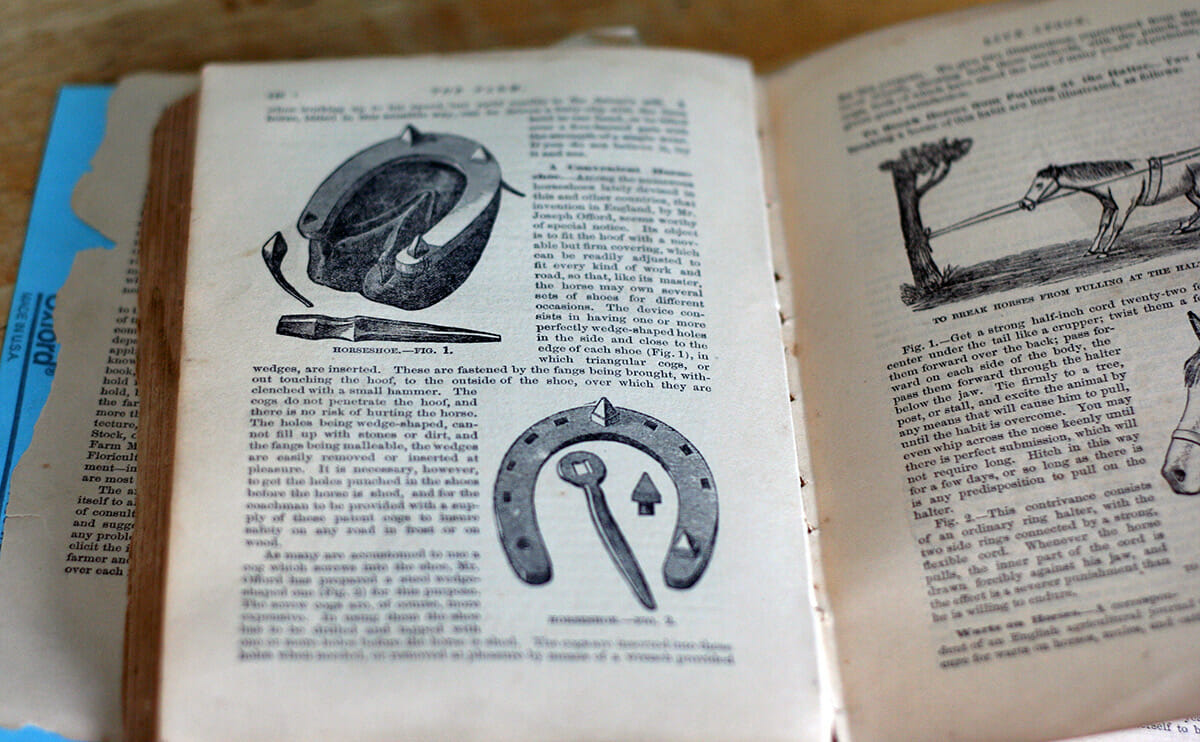

It may be over 125 years old, but The Farm & Household Encyclopedia is still chockfull of useful advice (as well as a few things you should never, ever do).

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]1. Birds are farmers’ friends[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]The swallow, swift, and hawk are the guardians of the atmosphere. They check the increase of insects that otherwise would overload it. Blackbirds, crows, thrushes, and larks protect the surface of the soil. It is an undoubted fact that if the birds were all swept off the face of the earth man could not live upon it. The long-persecuted crow has been found by actual experience to do more good by the vast quantities of grubs and insects he devours than the harm he does in the grains of corn he pulls up. He is, after all, rather a friend than an enemy to the farmer.[/mf_blockquote]

A growing body of science from around the world supports this idea, says Amanda Rodewald, director of conservation science at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. In Costa Rica, researchers found that birds foraging on coffee bushes reduced infestation of the coffee berry borer beetle by 50 percent, saving farmers between $75 and $310 in damages per hectare per year. In East Africa, aphid and thrip infestation was found to increase dramatically when birds were excluded from garden plots, and research in Spain suggests that kestrels and barn owls provide valuable vole-control services for farms.

That birds are such valuable farm workers, Rodewald says, is one more reason to manage entire landscapes to keep bird populations at healthy levels.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]2. Bees like buckwheat[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]Buckwheat is valuable as a honey plant, as it can be made to bloom when there would otherwise be a dearth of flowers. The honey is dark, but is preferred to all other kinds by some people.[/mf_blockquote]

Still true, says Mary Ross of the Mohawk Valley Trading Company. One reason that buckwheat remains valuable as a bee forage is that timed plantings allow it to continue blooming through the fall when, indeed, there can be a dearth of other flowers. “Buckwheat honey has a deep, dark brown color, strong pungent, molasses-like earthy flavor and is high-century Pieces of Farm Advice in mineral content and antioxidant compounds,” says Ross. Some people don’t prefer the strong taste, but buckwheat honey’s medicinal qualities have won it a large following. To capture its health benefits, Ross notes, it should be eaten raw.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]3. Treat your winter squash gently[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]Squashes to keep well must be well ripened, be gathered before heavy frosts come, be well dried, the shell should be well glazed over, they should be kept where the temperature is very even, never very cold, or very hot; in handling, great care should be taken not to bruise them; this is of the highest importance.[/mf_blockquote]

Also still true, according to Jim Myers, professor of vegetable breeding and genetics at Oregon State University. “Rough handling is easy to do,” says Myers. “That’s probably the number one mistake. Think about your squash as if they’re eggs and handle them that way.”

Picking good storage varieties is important. Of the four main domesticated squash species, Cucurbita maxima squash (includes hubbards, buttercups, kabochas) have the hardest rinds and keep the longest. On the other end of the spectrum are the Cucurbita pepo squashes (delicatas, acorns, summer squashes), which tend to have the shortest shelf lives.

Storage temperature recommendations today are a bit more precise: between 50 and 55 degrees is best. Another modern addition to the list is the hot water dip. Submerging winter squash for three minutes in 140-degree water will kill many of the microbes on the skin that otherwise could hasten the squash’s demise, says Myers.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]4. Field peas make a great green manure[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]I have tried peas as a fallow crop for the past three years, and find them the best and cheapest substitute for barn-yard manures that the poor land farmer can find. If all the farmers would use every means in their power to feed and improve their lands, we would soon have a different country from the present.[/mf_blockquote]

Legumes like the field pea (AKA black peas, Austrian winter peas, spring peas or Canadian field peas) still are great cover crops that can help farmers reduce erosion, retain moisture in their fields and improve their yields. Field peas “certainly provide a lot of nitrogen,” says Andy Clark, communications director for Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education, and the editor of Managing Cover Crops Profitably.

Today, Clark notes, few farmers have the luxury of fallowing a crop for an entire growing season (with some exception out West, where a summer crop of field peas can maintain soil moisture through a dry summer, prior to wheat planting in the fall.) As a winter cover crop, however, field peas can still be a good bet.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]5. Grow Bartletts, young man[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]Here is [a list], made up after much study and inquiry, which it is believed will not vary greatly from the list which a hundred of the best growers in the best pear sections of New England would recommend: 1. Bartlett. 2. Seckel. 3. Sheldon. 4. Beurre d’Anjou. 5. Duchesse d’Angouleme. 6. Beurre Bosc. 7. Lawrence 8. Vicar of Wakefield.[/mf_blockquote]

The large majority of commercial pear production has moved West ”“ 84 percent of the nation’s crop is now grown in Washington and Oregon. But among that which remains in New England, Bartlett and Bosc are the most widely grown, according to Jon Clements, a tree fruit specialist with the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Seckel, Clements adds, is a variety often recommended for New England homeowners.

In the Pacific Northwest, Anjou, Bartlett and Bosc account for 90 percent of American pear production. According to the latest figures from the Pear Bureau Northwest, farmers there grew more than 440,000 tons of those varieties last year.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]6. Fences and trees are part of farm real estate; fence rails and processed lumber aren’t[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]When a farm is bought or sold, questions often arise as to what goes with it, and disputes may often be avoided if farmers know just what their farm deeds include. In brief, the conveyance includes the land, the buildings upon it and all such chattels or articles as have become so attached or fixed to the soil or to the buildings. All fences on the farm go, but not fencing materials if bought elsewhere and piled upon the farm, and not yet built into a fence. Standing trees, of course, are a part of the farm; so are trees cut or blown down, if left where they fall, but not if corded up for sale; the wood has then become personal property.[/mf_blockquote]

All of this remains fairly standard practice in the 21st century says Jeremy Litwiller, a realtor in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley who specializes in farm and land sales. That said, fence rails, wood corded up for sale, farm equipment, bales of hay and other personal property items often become points of negotiation in a sales contract ”“ much as the stove and washing machine often convey with a home when you buy it. Particularly when the seller is an heir with no plans to farm in the future he or she will price the place to include these bits of personal property with the actual real estate, Litwiller says.

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]7. Make sure your horse doesn’t eat too fast.[/mf_h5]

[mf_blockquote layout=”left”]Scouring is caused by too rapid eating, which can be prevented by putting half a dozen pebbles half the size of the fist into the manger with the oats.[/mf_blockquote]

Horses in 2014 still need some help taking it nice and slow when they eat, and rocks in the feed trough are still a simple way to keep them on pace. “We still do that,” says Pete Burkholder, a large animal veterinarian based in Dayton, Va. “That’s a standard recommendation.”

[mf_h5 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Extra bonus content: a very bad piece of old farm advice[/mf_h5]

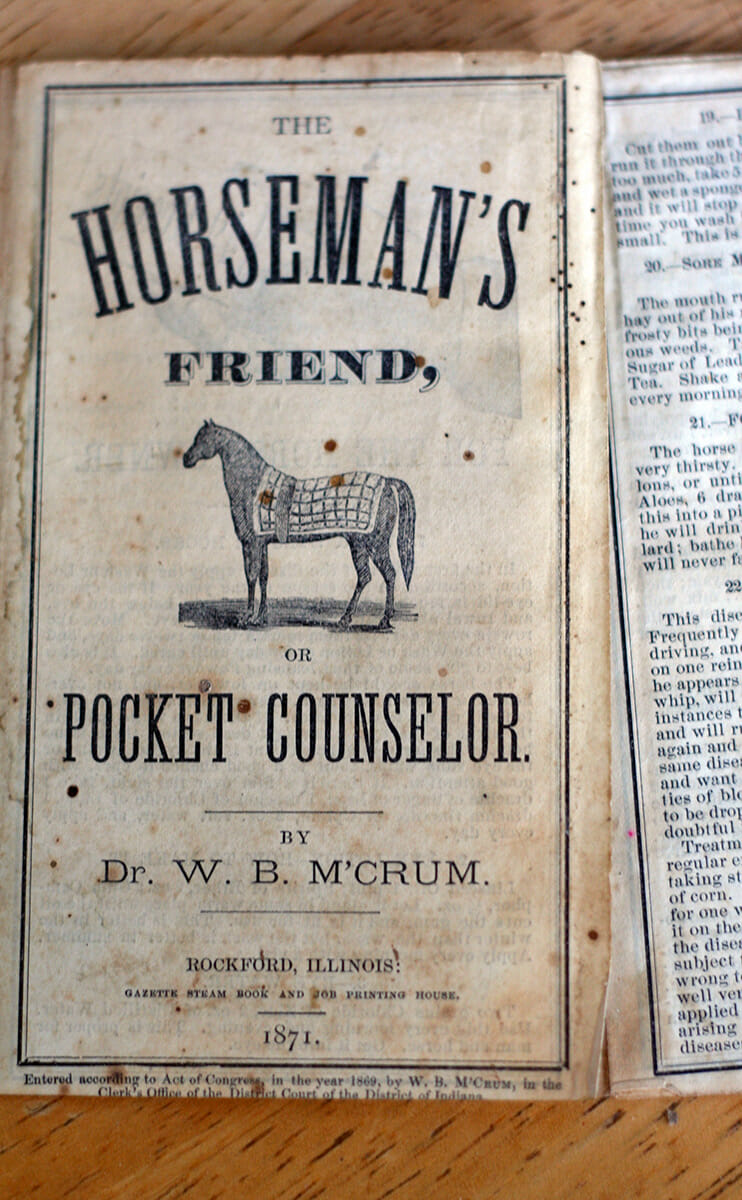

One of the miscellaneous pamphlets tucked inside the encyclopedia is an older brochure entitled The Horseman’s Friend, or Pocket Counselor, published in 1871 by a Dr. W.B. M’Crum. In the brochure, M’Crum offers instruction on how to treat dozens of common horse ailments, including “weak eyes or hooks.” If the horse’s eyes or lids are swollen, he recommended “bleed[ing] the vein below the eye.”

This is definitely, certainly not good advice. “It’s just crazy,” says Burkholder. Bleeding sick animals is just as bad an idea as bleeding sick people ”“ although he notes, in M’Crum’s defense, they didn’t really know any better back then.

Very thought provoking ideas…