The Definitive Guide to Choosing the Perfect Turkey

In which we decode turkey labels, tell you how to buy from a responsible, humane turkey farmer and more.

The Definitive Guide to Choosing the Perfect Turkey

In which we decode turkey labels, tell you how to buy from a responsible, humane turkey farmer and more.

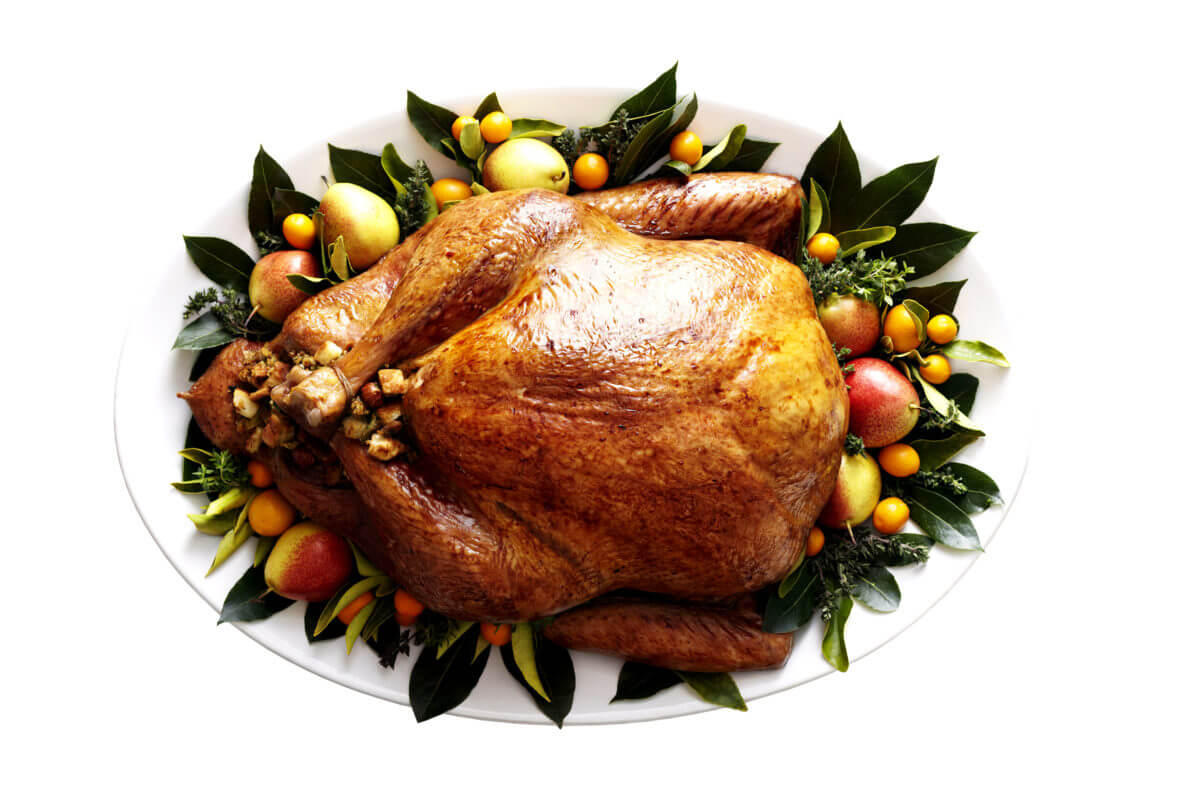

Before you roast your turkey to glorious perfection, you’ve got to start with the right bird. And that starts with educating yourself. And that’s why you should read this story.Shutterstock / Sayers1

Cooking Thanksgiving dinner for a household of bickering family members is trouble enough. We can’t help you there, but we can help with the pre-Thanksgiving stress: heed these tips to obtain the perfect bird, without all the hassle.

Remember, you’ll need a turkey that weighs at least one pound per person to be fed, more if you want leftovers. And if buying frozen, don’t forget to start defrosting it in the refrigerator long before Thanksgiving — one day per four pounds of meat is a good rule of thumb.

Start Looking Early

If you want a truly artisanal, pastured turkey from a farmer that grows their own turkey feed and pets and cuddles each bird every day, you need to start really early — like January. This is typically when farmers of this sort, who might only raise 10 or 20 turkeys each year, start taking orders for Thanksgiving. That’s because they’ll start raising baby turkeys in early spring and they like to have a guaranteed buyer for each mature bird come November.

Missed the boat on pre-hatch ordering? You still have no time to waste. Small-flock farmers sometimes raise extra birds, but the chances that all have been spoken for by the third week of November are high. Even if you’re going to buy from a store or aggregator that specializes in sourcing locally (they likely deal with mid-size farmers), plan on placing your order by Halloween at the latest, as they’re apt to sell out — the demand for high-quality turkey far exceeds supply.

Fortunately, there’s an easy way to find a wholesome turkey farmer near you: www.localharvest.org provides a nationwide database.

Read Those Labels Carefully

If you’re getting your turkey straight from a farmer who allows you to come and see how, and on what foods, the birds are raised, they may be of such a small scale that they haven’t bothered with a bunch of fancy certifications, and may not have labels per se. But in this case, you can see for yourself whether the bird lives crammed in a barn ankle deep in excrement or in a verdant pasture with acorns and caterpillars to graze on.

In cases where labels are provided, here’s what to look out for:

Antibiotic-free (and similar wording): This means exactly what it says, though it’s worth noting that the USDA does not require on-farm inspections to verify this claim.

Certified Organic: This means the animal was fed certified organic, non-GMO feed; was not administered antibiotics or growth hormones; and had some form of outdoor access. Though it doesn’t guarantee it was free to roam each day outdoors.

Free-Range: Legally-speaking, this means only that the animals have access to the outdoors, but says nothing about the quality or size of the outdoor space, or how much of their life the animal spent there.

Grass-Fed: This label pertains to ruminants, not poultry. Turkeys do consume plant matter when given access, but the bulk of their natural diet comes from insect, nuts and seeds.

Humane labels: Numerous labels and certifications allude to how the turkey was treated and what it’s living space was like, but it’s important to be aware that some of these have standards that are only marginally better than typical factory farming practices (note that “humanely raised” is a meaningless, unregulated term). Animal Welfare Approved and Global Animal Partnership (rated 4 or higher) are two certifications with fairly rigorous standards and enforcement protocols, though only the former audits processing facilities to ensure compliance with humane slaughter practices.

No Growth Hormones: This is gibberish when it comes to turkeys, as federal law prohibits the use of growth hormones in all poultry.

Natural: This means that no artificial ingredients have been added to the meat, but says nothing about how the animal was raised, including whether antibiotics were used.

Pasture-Raised (or pastured): This means the animal was free to roam each day outdoors, but the term is not regulated by the USDA, so it is essentially meaningless unless you can go to the farm and see for yourself (except in conjunction with the Certified Humane label — this organization enforces standards for pastured poultry).

Heritage vs. Industrial

Virtually all store-bought turkeys are a single breed: the Broad-Breasted White, a fast-growing bird with an enormous breast favored by factory farmers. Broad-Breasted Whites have little else to recommend them and are so breast-heavy that they can barely walk, let alone fly. It seems this bird’s breeders had little in mind other than profits, as Broad-Breasted Whites cannot reproduce without human intervention and are notoriously prone to health problems — part of why they are routinely pumped full of antibiotics.

Heritage breed turkeys comprise virtually every other turkey the planet has known throughout history. These breeds are generally at least 50 years old, if not several hundred years old. They come in a dazzling array of plumage colors and some have specialized traits that allow them to adapt to different climatic regions. Perhaps most importantly, they are fully functioning animals, able to walk, fly and mate. They are also good foragers — Broad Breasted Whites have trouble finding enough food when turned out on pasture.

Heritage turkeys were nearly extinct 20 years ago, but increased consumer demand has fueled a renaissance. Today the Livestock Conservancy lists a dozen widely available heritage breeds, including Narragansetts, Slates, Royal Palms and Bourbon Reds.

But be forewarned: heritage turkeys typically pack a much small percentage of white meat than most modern eaters are used to.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Brian Barth, Modern Farmer

November 7, 2018

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreShare With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.