The Community Organizing Effort That Helped Save an Urban Farm in New Orleans

A park had plans on building a road through a beloved urban farm and youth program in New Orleans. But the farm’s supporters weren’t having it.

The Community Organizing Effort That Helped Save an Urban Farm in New Orleans

A park had plans on building a road through a beloved urban farm and youth program in New Orleans. But the farm’s supporters weren’t having it.

Hundreds of supporters of Grow Dat Youth Farm showed up to a City Park Conservancy public planning meeting at Dillard University to voice their concerns about the park’s plan to build a road through the farm in March. Photo by Minh Ha/Verite News.

This story is part of a partnership between Verite News and Modern Farmer. Verite News is nonprofit news outlet covering New Orleans. You can read more of their work here.

Chekeita Strong stood up in front of a crowd in New Orleans last April, introduced herself, and began giving instructions. There were about 70 people in the space, a wooden deck inside of New Orleans City Park. And the 17-year-old needed them all—the other teenagers, the adults, anyone who would listen—to pitch in.

“If you have one of these flyers, go post it in your community or your local neighborhood, your local coffee shop, library, etcetera,” she says, “and continue sharing the petition, continue signing the petition.”

Everyone was there that night for what at the time seemed, at least to outsiders, like a quixotic goal: putting the brakes on a major public works project that threatened the future of a place they loved. Strong, then 17, was by day a senior at Warren Easton High School. But she was also a crew member at Grow Dat Youth Farm, an organization that teaches young people like herself leadership skills while they learn about sustainable agriculture.

Grow Dat is a seven-acre urban farm with 13 full-time adult staff, and a rotating crew of teenagers who work there after school. Founded in 2011, the group has provided more than 600 jobs for youth in New Orleans and taught nearly 19,000 students about sustainable agriculture during field trips.

For the entirety of its existence, Grow Dat has maintained a campus at City Park, the city’s largest park.

That night, in Grow Dat’s longtime home, Strong and the team with which she worked at the farm, the Open Oranges, were taking on another role: participants in a community organizing campaign.

Strong and the other teenage staff at the farm had been preparing for this work for the past couple of months. Role-playing with each other, they had worked on their public speaking skills and practiced answering media questions—all since they learned that Grow Dat might soon be displaced from the park to make way for a new road.

Grow Dat has transformed its bit of land into a sustainability oasis. The farm’s adult and youth staff grow and harvest a variety of produce—satsumas, kale, carrots, okra, cherry tomatoes and basil—from the fields, fruit trees, and a memorial garden. They sell some of it to the public and donate some to local charities, eating the rest themselves at the campus. The structure of the eco-campus, as Grow Dat staff refer to the buildings next to the fields, is made up primarily of repurposed shipping containers.

From the right angle, the Grow Dat site almost appears secluded. A bayou, used by locals to kayak, and a small forest buffer the north and west sides of the campus. Thickets of cypress and willow trees separate clusters of fields from each other. But it’s only a few minutes walk away from some of City Park’s most well-known amenities—such as the New Orleans Museum of Art—and the busy roads and densely populated neighborhoods that surround the park.

“Our location is ideal because it is in the center of the park, the heart of the park. It is a completely open, public space. So, there are no fences at Grow Dat. The public can pass through and see our programming in action and admire our fields,” says Callie Rubbins-Breen, co-executive director of Grow Dat.

“We’re situated right along the lagoon and have spent years fostering that ecosystem and maintaining it and stewarding it. I think, for the urban youth of New Orleans, coming to a space that feels both slightly manicured and agricultural but also very natural is both soothing and educational and inspiring for people.”

But they don’t own the land. Grow Dat is a tenant of City Park, which is publicly owned but managed by a private nonprofit called the City Park Conservancy.

Late last year, Grow Dat staff learned that park management might force them to relocate. Soon, a coalition of supporters—made up of teenagers, parents, activists, lawyers and educators—organized to fight. Their plan: Stir up broader community support for the farm and against its eviction.

TAKE ACTION

Learn how to start your own urban farm.

Some had experience with redevelopment battles against powerful interests, but, for most of them, especially the teens, this was their first experience with this kind of effort. And they were up against a sophisticated, well-funded group: the City Park Conservancy, a multimillion-dollar nonprofit hired by the park’s appointed governing board in 2022 to run the park.

Earlier this year, the conservancy was finalizing a major redevelopment plan for City Park. Ot had hired Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc.—a design firm that had worked on the Brooklyn Bridge Park in New York City, the George W. Bush Presidential Center and public spaces at Harvard and Princeton—in a $2.8million contract to create a plan for the redevelopment.

Just weeks before Grow Dat supporters met that April night, the City Park Conservancy—which for months had hinted, not subtly, that a road might have to run through the farm’s campus—finally confirmed it. Park officials said they wouldn’t renew Grow Dat’s lease when it expired.

It appeared that was it for the farm, at least in City Park. The conservancy wanted a road and couldn’t be forced to sign a new lease. This was an unwinnable fight for Grow Dat.

But it won.

Farm staff circulated petitions, planned public meetings and worked the media, generating thousands of words of local media coverage. People with no direct connection to the farm began showing up to City Park governing board meetings, urging the conservancy to back off the farm.

In August, the park announced that it had rethought its plan. Grow Dat would be able to stay.

“I think, sometimes, when people grapple with something that they don’t feel like they have much impact in changing, people flounder, and feel despair,” says Rubbins-Breen. “But this, I think, really did galvanize people.”

A master plan and an existential threat

In late 2023 and through much of this year, however, the fate of Grow Dat has hung in the balance.

Last year, City Park’s leadership began the master planning process—to “shape the next 100 years of the park,” as Cara Lambright, then-CEO of the City Park Conservancy, put it when the project launched.

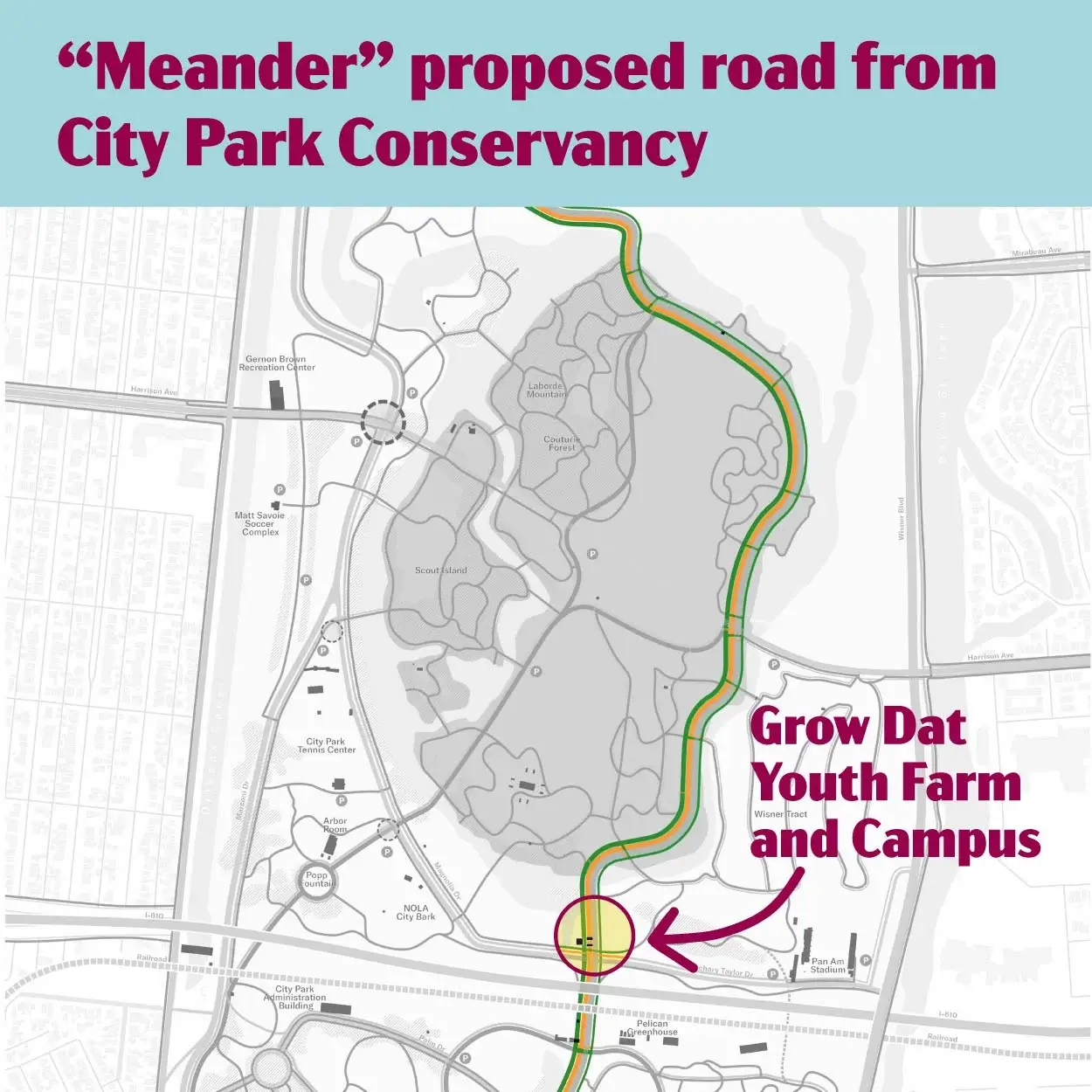

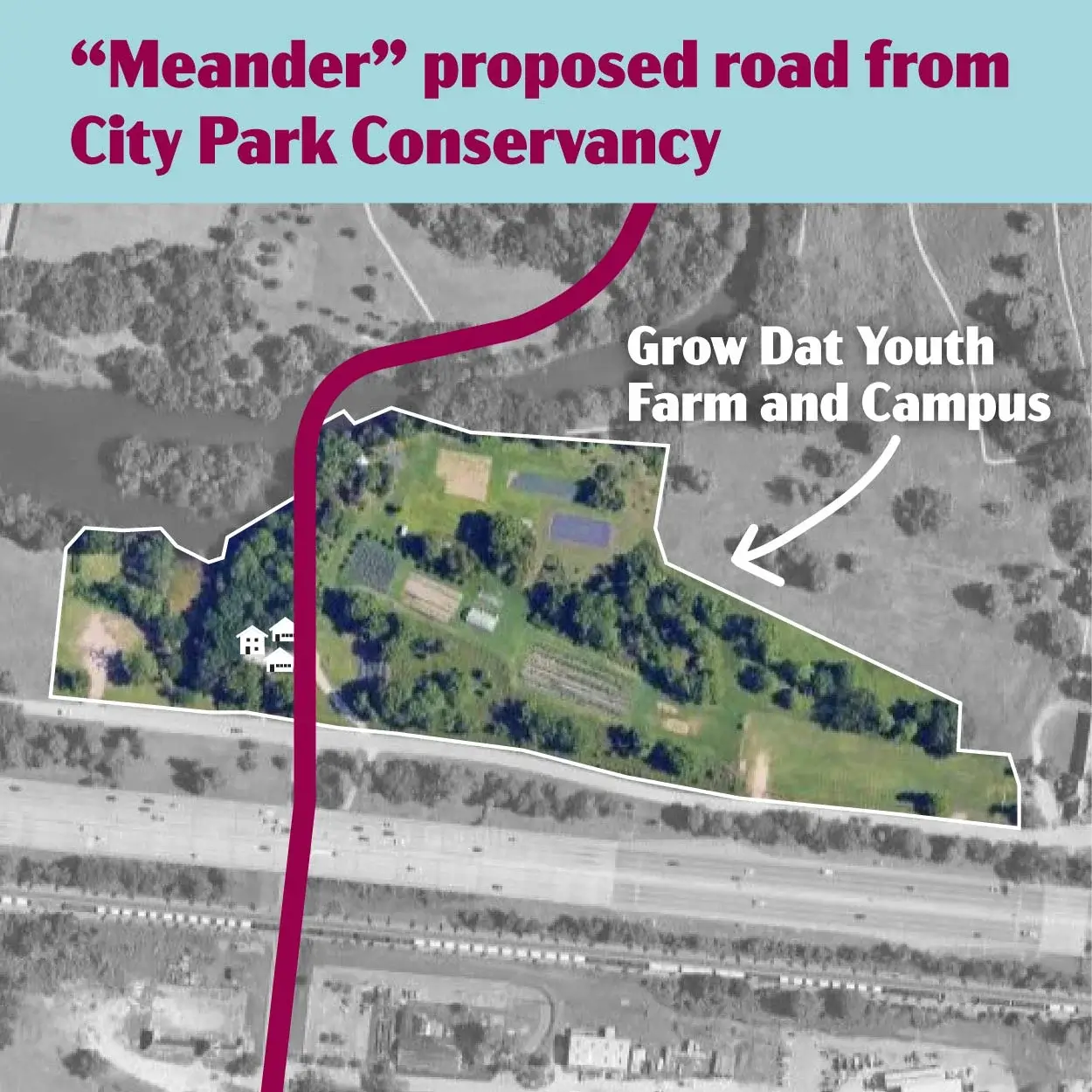

A key goal of the master plan project, which she says could take up to 20 years and $200 million to complete, was to create greater access to and circulation throughout the park. So, they proposed building a road through the middle of the park—a “promenade,” they called it—that would connect its north and south sides.

Staff and supporters of the farm say they first heard about the planned road in December 2023 during a public meeting the park held on its master plan. City Park Conservancy staff showed mockups of what the new park might look like after the redevelopment. Grow Dat wasn’t on any of them.

“In our understanding, the road and Grow Dat don’t exist together. It’s an either or,” Rubbins-Breen said in March. City Park officials confirmed that they were planning to force the farm to relocate around the same time.

It was an existential threat for the farm, which contributes tens of thousands of pounds of produce to New Orleans’ food system each year, and its youth program. Even if it was to find a new location in the park or the city, it would take years to get back to the capacity that it spent more than a decade building at its present location.

And it was a blow to the youths who staffed and visited the farm, who had come to think of it as a refuge. The park has become a hub for racial and economic diversity and LGBTQIA+ inclusion in the city.

“It was always about racial justice. It was also always about spaces for youth leadership,” says Nikki Thanos, a founding member of Friends of Grow Dat, a group that formed to advocate for keeping the farm in its present space. “And I think at the heart of it, it was always a fight about public participation and what democracy means in public spaces.”

Friends of Grow Dat

Over the 13 years that Grow Dat has been in existence, the farm has racked up supporters and goodwill throughout New Orleans through its commitment to education and sustainable agriculture.

Hundreds of young people have graduated from its youth leadership programs, which teaches communication and organizational skills. It has a community-supported agriculture, or CSA, program through which many more residents have become acquainted with the farm’s ability to grow and harvest a myriad of chemical-free, fresh produce.

Grow Dat’s campus is a gathering space that frequently hosts community events, such as tours of the farm for school field trips, public dinners and workshops where people can learn about the history of the land on which the farm sits in City Park. They learn how it’s on land called Bulbancha by Indigenous people from the region, how it used to be a plantation and then, once it became a park, how it was white-only until 1958.

While the maps Grow Dat staff and supporters were shown in December appeared to show that the park would not be around much longer, City Park Conservancy officials were tight-lipped at first about their plans.

Thanos says a loosely organized group of supporters started putting the pieces together about the park’s position on the farm in the months between its December meeting and another one planned for late March. A few weeks before the March meeting, City Park officials confirmed to Verite News that relocating the farm in favor of a road was a possibility.

“I think the early wave of emotions was like dismay, anger, confusion, disappointment “[and] a little bit of hope that maybe something could be salvaged,” says Thanos.

At the same time, there were similar emotions being felt by youth participants and full-time staff at Grow Dat. They wanted to advocate for Grow Dat—and eventually would—but the youth had to manage school, family, and extracurricular activities. And full-time staff had to deal with running the farm.

That’s where Friends of Grow Dat came in. Thanos and several other supporters of the farm formed the community organization in March to help advocate for the survival of the farm. They wanted to help give voice to Grow Dat using their skills from a variety of professions to advocate for the farm and connections with powerful people in the city to build important alliances for the cause.

“I think part of the vision for Friends of Grow Dat was to create some technical and capacity support, both on the mechanics of grassroots organizing but also a place to leverage some of the institutional relationships that people had outside of the Grow Dat arena,” says Thanos.

Two days before the March City Park Conservancy meeting, members of Friends of Grow Dat held a virtual planning meeting over Zoom. There were a few dozen people in attendance. Attendees split off into breakout rooms to discuss different aspects of City Park’s master plan, including the road.

People also shared their reasons for supporting the farm, including one mother of an alum of the program who said it was pivotal in her daughter’s development by helping mature as a person through the relationships she formed with her peers. Founding members of Friends of Grow Dat advertised T-shirts that people could buy to help support their efforts and encouraged attendees to show up to the meeting. They weren’t the only ones—the farm sent out emails and posted social media encouraging people to go to the upcoming master plan meeting.

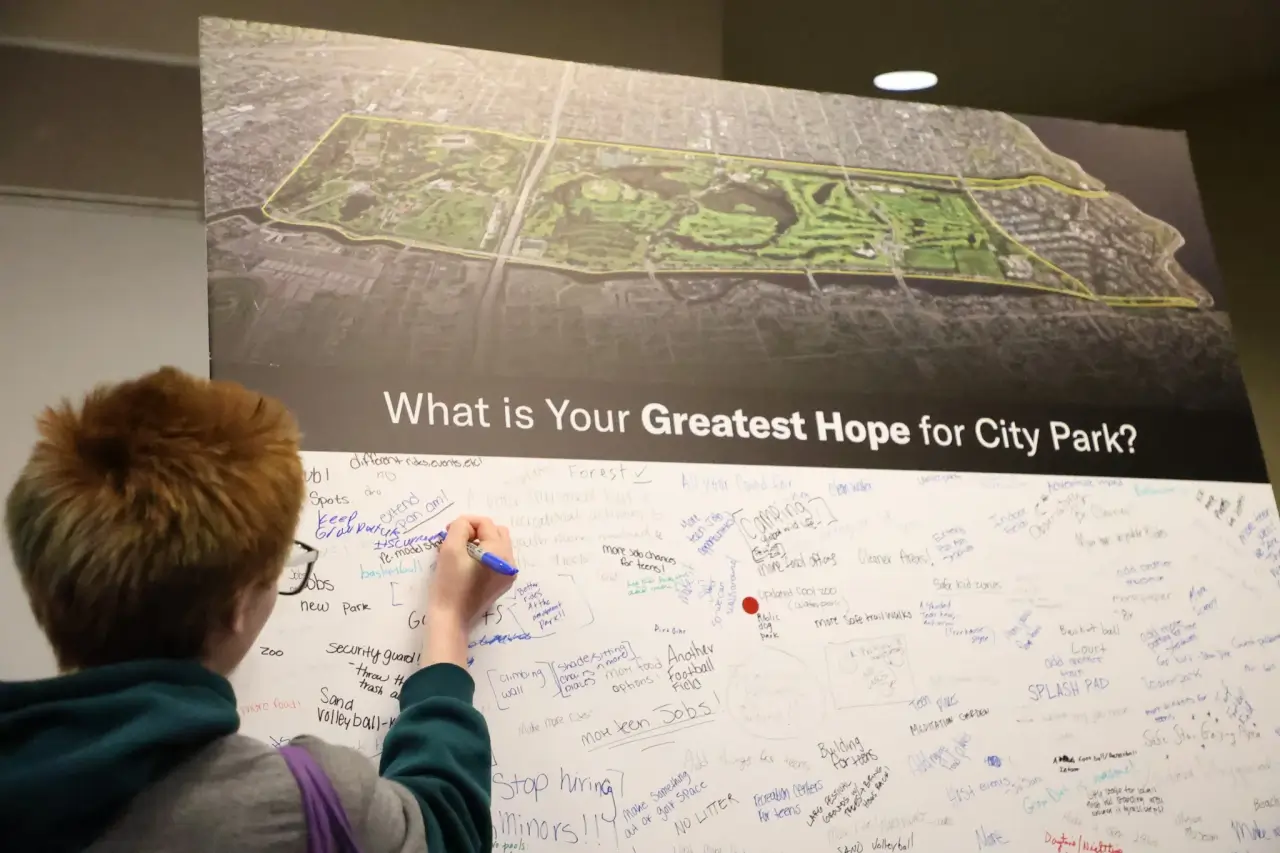

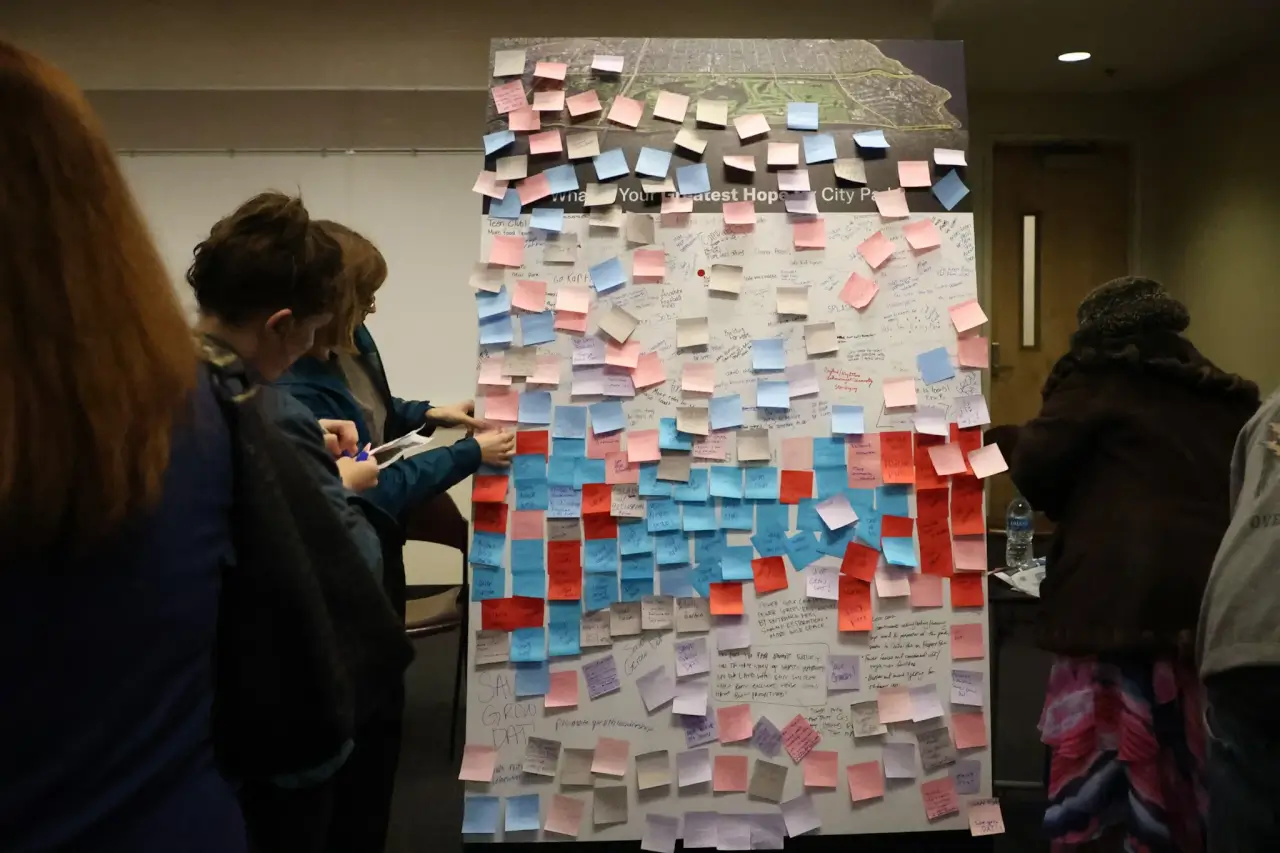

The master plan meeting was held at Dillard University on March 21. The meeting was supposed to be about water management projects in the new master plan.

But the focal point of the meeting quickly became about the road through Grow Dat. Hundreds of Grow Dat supporters—many of whom wore “Friends of Grow Dat” shirts displaying drawings of different types of produce—gathered around an enlarged map of the park and needled park leadership with questions and complaints about the proposed road.

This was the type of moment that the youth at Grow Dat had been training for during their role-play and public speaking sessions.

Local TV, radio and newspapers showed up to the meeting. Grow Dat supporters were there, prepared to answer press questions.

After much repeated chants and demands calling for City Park Conservancy CEO Cara Lambright to come out and speak with supporters, she did, answering questions and responding to concerns people had about the future of Grow Dat. She said the plan was a work in progress. She said the road would improve access to the park for people with disabilities. She said the park leadership liked the idea of having sustainable agriculture as part of the park, but supporters weren’t satisfied. They wanted a public forum exclusively about Grow Dat and, after cajoling from supporters, she agreed to have a public forum about the road and Grow Dat at a later date.

“It felt really empowering,” says Reid Lomax, who was a youth staffer in the program at the time. They remembered talking to some of the park’s leadership at that meeting, including Lambright, surrounded by supporters.

“I had my friends holding my back. My dad was right behind me. I had my co-workers around me. I had these adult supervisors around me that I trust and love very much,” says Lomax. “It was just like, ‘OMG, everyone’s here for Grow Dat.’”

The meeting was an inflection point in the fight to save the farm. Once on their backfoot, wondering how they could get the park to change its plans, youth participants, staff and supporters of the farm were now emboldened.

“It actually felt really good to realize, ‘Oh, we’re not fighting this battle alone’,” says Kendricka Kelly, another youth who was working at the farm then.

‘It was a little nerve-wracking at first’

Lomax, 18, started working at Grow Dat when they were 15. During their first two years in the program, they learned how to tend to crops, work with people from other backgrounds and lead groups of people.

“It felt like they were trying to take away my home a bit,” Lomax says of the plan to displace the farm. “Honestly, I was very frustrated. But that just turned into, like, OK, let’s figure out what I can do about this.”

That was the attitude of many of the youth who worked at Grow Dat at the time. Kelly, who also worked at the farm for three years, was heartbroken by the development. But rather than wait and see what would happen, she wanted to be part of the effort to save the farm.

“It was either we can try to go about this the smart way or make them upset and lose the farm,” she says.

Lomax and Kelly were part of an internal organizing effort at Grow Dat that was happening in parallel to the one happening with Friends of Grow Dat. The two of them and dozens of other youth who worked at the farm would spend parts of their shifts at the farm role-playing conversations with strangers or press interviews practicing their oratory skills in case they had to give public comment at Conservancy meetings and memorizing statistics about the impact of Grow Dat on New Orleans, such as how many teens had come through the program (more than 600) or how many pounds of produce they harvest each year (50,000).

In April, youth at the farm began hosting public meetings of their own where they invited members of the public to envision a more community-driven plan for the park’s future. During those meetings, young people who worked at the farm served as emcees and docents, gave presentations and facilitated discussions.

Some of what they did, such as guiding conversations, they learned as participants in the farm’s leadership program anyway, but other things, such as speaking to the press, were completely new to them.

LEARN MORE

What are the big issues for young people looking to farm? We ask them.

“It was a little nerve-wracking at first, I think because we were all a little uncertain of what could happen,” says Lomax. But through looking to their supervisors for guidance and working with their peers, they became more comfortable with the organizing effort.

“It felt a lot less stressful working with people who were in the same position as me because we were all learning,” they say, so it was just like “we gotta make sure that [Grow Dat] stays here. We gotta figure out what to do.”

Don’t stop fighting

About a week after the March planning meeting, City Park officials responded to emails from supporters of Grow Dat, who were lobbying the park to keep the farm in its place, saying they wouldn’t renew the farm’s lease after it expired in 2027. In the meantime, though, they’d started meeting with the farm’s leadership to discuss the proposed road.

Everything from the park helping the farm relocate to keeping the farm in its place was discussed, according to statements made by leadership of City Park and Grow Dat. But officials from the City Park Conservancy indicated that there were no changes to the plan to build the road.

Soon after, though, the park’s leadership began to reverse course. In April, the City Park Conservancy announced a pause to its master planning process in order to get more community input. Lambright mentioned the public uproar over Grow Dat as one of the reasons for the pause.

About two months later, Lambright resigned as CEO of the park to take a job in Houston at Hermann Park. “Since I’m no longer with the Conservancy, it doesn’t feel appropriate for me to give a response on this,” she wrote in an email to Verite News. “I’m very pleased that everything seems to be going in the right direction with the two organizations.” The forum Lambright agreed to back in March never happened.

Talks continued, although neither side was speaking publicly about the state of negotiations. Then, in mid-August, City Park and Grow Dat announced that they had reached a deal to keep the farm in its current location for up to 10 years.

“Now, we know that we have a place to be able to continue our programming and working with the youth who are the future of our city,” Julie Gable, co-executive director of Grow Dat, said at the City Park Improvement Association board meeting in August where the deal was approved.

Verite News reached out to current City Park leadership and members of the boards of the City Park Improvement Association and City Park Conservancy for comment on Grow Dat’s organizing efforts. City Park leadership said they didn’t have comment on the matter and board members either didn’t have time to comment or didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Some of the goals of the farm’s youth leadership program are to help them develop critical thinking skills, envision a just and sustainable world and work with others across differences to make change.

“At Grow Dat, we encourage young folks to analyze the state of our world today and advocate for a better future, advocate for a future they want to live in,” says Rubbins-Breen. “And so, involving them and learning alongside them, that felt very important to us. That is a foundation of our programming that we talk about and try to live every day that we’re here.”

Lomax and Kelly both say that Grow Dat was already a formative experience for them prior to participating in the organizing effort that saved the farm. But going through that struggle taught them both different lessons. Lomax says they learned about how easy it can be sometimes to get people to rally behind a simple mission, especially when people are already passionate about it.

Kelly says she learned to fight, no matter the odds.

“I feel like what I learned the most is if you want something, you have to fight for it, no matter how impossible it seems,” she says. “Even if it may look like it’s over with, don’t stop fighting until you know it’s over.”

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Drew Costley, Verite News, Modern Farmer

November 18, 2024

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.