Women Are Reclaiming Their Hunting Heritage

The surprising reasons fueling a hunting boom among women.

Women Are Reclaiming Their Hunting Heritage

The surprising reasons fueling a hunting boom among women.

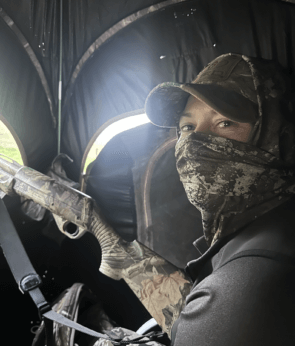

The view from a turkey blind on a cold spring morning. by author.

On a recent 48-degree spring morning, I left my warm bed well before dawn to meet a stranger with a big gun. I donned my Upstate New York mom’s version of camouflage (black jeans, giant brown rain boots, a green puffer), doused myself in tick spray and nosed my superannuated station wagon onto a network of country roads, then gravel lanes, lined by budding maple, beech and oak trees and sprouting fields of ferns and wildflowers that would lead me to the unmarked trailer I was set to arrive at around 4:30 a.m.

It was dark, with a sliver of a moon lending a Cheshire Cat, Alice in Wonderland eeriness to the inherent novelty of my planned morning of activities. I pulled past the “No Trespassing” signs and found the trailer, cheerfully lit up against the dark meadow quietly swaying in the breeze behind it.

I shook hands with the waiting stranger and grabbed one of the headlamps and a set of protective earmuffs (exposure to the sound of gunshots over time can damage your eardrums) on offer, and followed her—yes, her—into the woods, where we’d huddle in a blind for hours, waiting to see if any turkeys would show.

Cheryl Frank Sullivan, a research assistant professor of entomology at the University of Vermont, grew up around hunting in Upstate New York, but she was never interested in it. “I studied environmental science in college, and I didn’t see until a little later how hunting could fit into that,” says Sullivan. Many folks may change their minds about a stance they took when they were younger. But hunting is a topic that inherently brings up strong emotions. And crucially, it hasn’t always been portrayed as friendly or open to women looking to join up.

As I found out on that cold spring morning, that’s changing.

The hunt

Sullivan led me toward the blind she had set up, telling her story. (I don’t have a license to hunt, so I could only legally observe her hunting.) Like many other female hunters, the route she took to get where she is today was meandering but meaningful.

“For me, hunting has become a way of living and a way of being in the world and the woods,” said Sullivan as we sat in comfortable camp chairs inside a snug tent with windows we could zip and unzip as needed to see what was going on, disguise ourselves and—if all went well—Sullivan could target and shoot a gobbler.

Sullivan set up realistic (to me) looking hen turkey decoys in a patch of meadow in front of our ground hide. Hunters can also set up blinds in trees, but those are best utilized for deer hunts, or they can just completely camouflage themselves and set up next to a tree on the ground or move quietly from place to place, she says.

“Turkeys have eagle eyes, so wearing camo and staying very still is important, and they have incredible hearing, which is why I’m whispering,” said Sullivan.

In a bid to draw the birds, Sullivan brought out a slate call, scratching the striker against the slate to imitate a turkey’s distinct vocalizations. Sullivan, who seemed familiar with all of the state’s hunting regulations, was only able to target gobblers or male turkeys.

“May is nesting season, so you can’t hunt hens,” said Sullivan. “We can also hunt from a half an hour before sunrise to noon.”

Following the rules, which vary state to state and are generally handled by a wildlife management agency, is important to Sullivan and all of the hunters she knows.

Women have always hunted

An army of female hunters may seem modern, but recent studies show it’s anything but.

For millennia, the notion that men hunted and women gathered dominated the academic study of early human life. The popular imagination followed, and for many years, the idea that society would function better if men and women would do what comes “naturally” to them—in other words, stop trying to wedge your way into boardrooms and onto battlefields, ladies—seemed like common sense in many circles.

But science and new discoveries have overturned that paradigm. New research out of the University of Washington and Seattle Pacific University shows that, around 200,000 years ago, when Homo sapiens began their slow trudge toward space travel and excessive screen time, women were responsible for hunting, right alongside the men.

The findings published in PLOS One found that, in 79 percent of societies across the world for which scientists were able to find direct evidence, women were hunting with purpose and their own tools. Girls were actively encouraged to learn how to join the hunt.

Sullivan’s approach to hunting—as a way to respect and care for the land and the intricate ecosystem and food chain that it supports—reflects a consistent shift in the culture of hunting, says Mandy Harling, director of education and outreach programs at the National Wild Turkey Federation [NWTF], a foundation dedicated to wild turkey conservation throughout North America.

When the organization was founded in 1973, hunting heritage was foundational to NWTF’s mission. Since 2012, when it launched a refreshed preservation push, the NWTF has conserved or enhanced more than four million acres of wild land for turkeys and hunters, and it has opened public access to hunting on 600,000-plus acres of land.

Conservation and hunting, while at first glance perhaps unlikely bedfellows, share many of the same goals, says Harling.

“Clean water is essential for all living things on earth, and where there is clean water, there are turkeys,” says Harling. “We work with partners to create healthier forests and watersheds. And when we manage a forest for wild turkey habitat, we also improve the land for all wildlife and the humans who live around it.”

Getting women interested in and invested in hunting is also part of the NWTF’s long-term strategy.

“We formally began organizing women in outdoor programs in 1998,” says Harling. “We have found that the conservation aspect is an important aspect of the culture of hunting that attracts women.”

While only 10 percent to 15 percent of hunters in the US are currently women, that number is on the rise, with the number of women applying for hunting permits almost equaling that of men and more organizations set up to train women hunters. Some states such as Maine have programs specifically for women organized by the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. There are also nonprofits such as Doe Camp Nation and companies such as Artemis and Wild Sheep which offer retreats and training programs for would-be women hunters.

Maya Holschuh, a 25-year-old Wilmington, VT resident who started hunting at 21, says the practice has been empowering and transformative.

“I feel like it’s a much more ethical way to consume meat. I know how the animal died, I know it lived a great life in the wild and I know it wasn’t raised in captivity and pumped full of hormones,” says Holschuh.

On my first foray into the hunting world, there were no kills. The experience left me with the same feeling I get after the first day of skiing every year: I connected with the natural world on a deep level that I somehow forget I know how to plumb on other nature excursions. I was OK with my performance, but I could do better next time. I know what I’d change. It left me sated but wanting more.

I love eating meat. But I want to eat less beef because I know that continuing to support cattle farming with my burger habit is more destructive to the ecosystem and surrounding community than, say, shooting one deer or a handful of turkeys and eating their meat for an entire season. I opt for organic, grassfed everythin, and have developed a taste for wild meat thanks to my generous hunting friends who are always willing to share their hauls.

Hunting seems like the next step in my CSA-joining, farmer’s market-shopping food journey. Will I run out and get a hunting license? I haven’t yet. But I’m intrigued by the idea of joining my sisters in arms.

Sullivan has introduced countless women to hunting and fishing, and she has instructed groups on weekend retreats through associations such as Vermont Outdoors Woman and Vermont Outdoor Guide Association.

“If you want to learn to hunt, reaching out to an organization that guides women is a great place to start,” says Sullivan. “You’ll get guidance on technique but also learn what kind of licenses and gear you’ll need. Plus, you’ll be creating a network of other female hunters who are eager to learn.”

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Kathleen Willcox, Modern Farmer

June 3, 2024

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

What a stunning piece! I know Kathleen Willcox as a superb writer on wine and sustainability, but this article elevates my appreciation of her journalism to new heights. She opened, and changed, my mind in the best way.

In a cultural shift, women are reclaiming their hunting heritage, challenging traditional gender roles. With a surge in female hunters, there’s a newfound recognition of women’s prowess in the field. This resurgence reflects a desire for equality and connection to nature, as women embrace the thrill of the hunt and the skills passed down through generations. It marks a significant step towards inclusivity and diversity in outdoor pursuits.