The EPA Just Passed the First-Ever Federal Regulations for ‘Forever Chemicals’ in Drinking Water. Here are the Top Five Things You Need to Know.

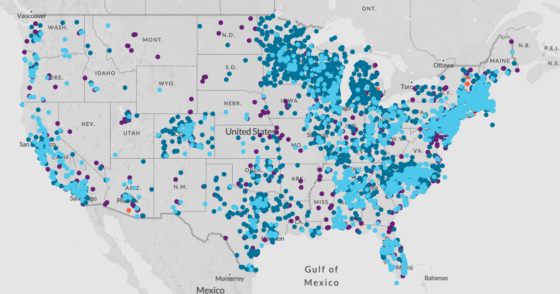

Of the thousands of "forever chemicals" out there, the Environmental Protection Agency just passed a drinking water standard for a small handful of them. Here’s what it means for you.