Agricultural Runoff Pollutes Well Water, a ‘Public Health Crisis In the Making’

More than 1 million Minnesotans drink from private wells, but few know if their water is safe, experts say.

Agricultural Runoff Pollutes Well Water, a ‘Public Health Crisis In the Making’

More than 1 million Minnesotans drink from private wells, but few know if their water is safe, experts say.

Hydrologist Paul Wotzka looks out at Beaver Creek in Wabasha County, Minnesota Nicole Neri/for Investigate Midwest

The water that pours out of the taps at Jeff Broberg’s house is crystal clear, refreshing and odorless.

But Broberg, 68, doesn’t drink it. The issue is only visible on the molecular scale.

Like Broberg, many rural Minnesotans rely on private wells, which tap into groundwater systems spread underneath rolling crop fields and livestock operations. When nitrates from the agriculture operations seep into the water and make it unsafe to drink, well owners pay the price.

When Broberg, a geologist, bought his farm in 1986, he tested the well water. The nitrate levels were elevated, but they were still below the Environmental Protection Agency’s contamination limit. With each periodic test, the nitrate concentration increased until it surpassed the EPA’s safety standard of 10 parts per million in 1990 and eventually climbed to 22 ppm.

Nitrogen is a naturally occurring element critical to human and plant life, and it’s a core component of the fertilizers and manure spread in mass quantities on farms in the Midwest. When the nitrogen mixes with oxygenated water, it forms nitrate.

Drinking water with high levels of nitrate can cause methemoglobinemia or “blue baby syndrome,” a potentially life-threatening condition affecting the blood’s ability to carry oxygen throughout the body. Nitrates also have been linked to thyroid disease and certain cancers.

Nitrate pollution is largely caused by agricultural runoff. Rainwater picks up the nitrogen in fertilizer and manure and carries it to bodies of water. When nitrate reaches the underground drinking water supply, it’s the well owners’ responsibility to treat their water—with limited, often expensive options—or find another water source. In Minnesota, nitrate pollution disproportionately impacts low-income communities, according to a 2021 study by the Environmental Working Group.

The American Farm Bureau Federation, the largest lobbying group representing farmers, opposes any mandatory measures that would reduce commercial fertilizer use, often referred to as “low-input” or “reduced-input” practices.

“There isn’t a one-sized approach to the implementation of reduced-input farming practices, especially in a state like Minnesota with a diverse climate, soil and crop production range,” a Minnesota Farm Bureau representative said in an email.

After the nitrate concentration in his water reached unsafe levels, Broberg drove his truck to a friend’s property every two weeks, where he filled jugs and hauled them back to his home. A couple of years ago, he decided he was “too old” to keep up with the routine and spent more than $250 on a reverse osmosis filtration system.

The standalone dispenser, separate from all other taps in his home, uses filter cartridges that cost upwards of $100 and need to be replaced yearly.

Broberg is trying to help other private well owners dealing with nitrate pollution. He co-founded the Minnesota Well Owners Organization with hydrologist and neighbor Paul Wotzka. Together, they host water testing clinics and advocate for policy changes that would benefit water quality for rural well owners.

In Minnesota, 1.2 million people drink well water. A 2016 Minnesota Department of Health survey found fewer than 20% of well owners regularly test their water.

“It’s a public health crisis in the making,” says Wotzka.

Government programs emphasize testing, lack funds for solutions

Recognizing the issue of nitrate pollution and its impact on private well owners, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture administered a program from 2013 to 2019 that offered free well water testing to residents of vulnerable townships.

The department tested more than 32,000 wells in 344 townships, mostly in the southeast and central parts of the state. In those areas, a combination of intensive agriculture and vulnerable geography—areas where groundwater is easily contaminated—resulted in a high risk of nitrate pollution.

Nine percent of the wells tested had nitrate levels over the safety standard, according to the program’s initial results.

“I think our township testing program has really brought to light that there’s a lot of vulnerable areas in Minnesota, and they’re generally happening in the vulnerable areas where there’s a lot of row crop production,” says Kim Kaiser, a hydrologist at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, who administered parts of the testing program.

The township testing program was meant to determine the impact of fertilizer runoff, so in its final well water dataset and analysis, officials removed wells that were likely contaminated for other reasons.

Poorly constructed wells and wells located near feedlots or septic systems were excluded from the final data. But these wells still represent a significant portion of households without safe drinking water.

In seven townships located in Rock County, Minnesota, more than a quarter of the wells tested were located on properties with livestock, and 34% were located less than 300 feet from an active or inactive feedlot.

In that testing area, half of the 171 wells tested were over the safety standard for nitrate. MDH estimated that more than 900 residents could be consuming water with unsafe levels of nitrate.

For wells that tested high in nitrates, Minnesota Department of Agriculture staff reached out to the well owners to educate them on options available to remedy the issue. While MDA doesn’t pay for remedies, such as purchasing bottled water, installing a filter or replacing a well, the Minnesota Department of Health has some limited funds for that purpose, says MDH water policy manager Tannie Eshenaur.

“We have some information on financial support, but it’s very limited and it’s not easy to get,” says Eshenaur. “There’s not a lot available for folks if they face financial challenges. There just aren’t a lot of programs out there.”

Because nitrate particles are so small, many common methods of water filtration don’t remove nitrate. Reverse osmosis filters are most effective in removing nitrates, but they’re more expensive than other kinds of filter systems.

Many well owners also hire plumbers to ensure the system is installed correctly. Because most home reverse osmosis systems are “point-of-use” filters, they are only connected to one tap, not the entire home. The filters also require replacement cartridges over time.

Eshenaur says MDH is requesting Clean Water funds to pay for solutions for private well owners, particularly those who are low-income and whose water is not safe to drink. Clean Water funds are taxpayer dollars distributed by Minnesota’s Clean Water Council with the goal of improving the state’s water quality.

Those funds would be used to expand on pilot programs such as Tap In, a program in southeast* Minnesota that helps low-income well owners remedy nitrate issues.

The pilot program started in 2021 with a $100,000 grant from the Clean Water Fund. The funds paid for well testing, installation of reverse osmosis systems, well repair and construction of new wells for low-income households.

The initial grant covered 186 tests, seven reverse osmosis filtration systems, six new wells and one well repair.

Reaching at-risk well owners a challenge

Well owners can be difficult to reach with public health messaging, says Jason Kloss, environmental health manager at Southwest Health and Human Services, the public health agency covering six counties in southwest Minnesota.

The agency offers water testing for multiple contaminants, including nitrates. The tests are free for those receiving assistance via the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

In the counties covered by Southwest Health and Human Services, many residents get water from the rural water system, in part because the shallow distance from the surface to groundwater makes wells vulnerable to pollution.

“We’ve tried advertising, we’ve tried promoting this, but it’s really difficult because the population that it pertains to is scattered,” says Kloss.

In order to test their water, well owners have to collect a sample and deliver it to the lab. If the testing determines the water is unsafe, the well owner then has to find a solution if they want to avoid drinking the polluted water—purchasing bottled water, installing a treatment system or even drilling a new well.

“That’s a lot of moving parts for an individual to follow through, and that’s another challenge,” says Kloss.

The lab Kloss oversees tested 81 samples for nitrates in 2021 and 74 through Dec. 2, 2022.

Terri Peters, district water manager for the Wabasha County Soil and Water Conservation District, says lack of education on drinking water risks is another reason well owners may not follow through on testing or treating water.

“One of the bigger challenges is that people sometimes don’t know or understand that they should be testing their wells for contaminants or testing for nitrates in general,” says Peters. “So, [we’re] trying to educate on that piece of it, that they should understand what’s in their drinking water.”

Wotzka says distrust of government agencies is another reason why well owners are hesitant to test their water, particularly through state programs.

Wotzka and Broberg have organized several water testing clinics since they founded the Minnesota Well Owners Organization in 2018, testing more than 1,300 wells.

“Biases that people have about testing their water are often fear-based,” says Wotzka.

Well owners have asked him if the government will force them to replace their wells, he says. Government agencies don’t have the authority to force well owners to make changes to their water source, even if pollution is detected.

A 2021 Environmental Working Group study found that community water systems most affected by nitrate pollution are more likely to be low-income. Data on well users is harder to come by because, unlike public water systems, well water is not regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Renters are another vulnerable group Minnesota Department of Public Health is targeting for outreach, says Eshenaur.

“Often in these areas, there isn’t a lot of affordable rental housing,” says Eshenaur. “Renters may not know whether the owner has tested the water or whether or not it’s safe to drink.”

Advocates want public policy to address root causes of pollution

Wooded hills surround Wotzka’s small farm, which overlooks row crop fields across the paved road.

When Wotzka bought the farm in 1997, the well—drilled in 1928—had high nitrate levels. Over the past 24 years, using organic farming practices such as opting for organic compost instead of commercial fertilizer, the nitrate level dropped until the compound was nearly nonexistent.

He pours glasses of water from his kitchen sink and serves them with pride.

“Everybody understands the importance of water down here,” he says.

Ben Daley, one of the owners of Daley Farm, a family-owned dairy operation in Winona County, says his family’s well water has also been impacted by the livestock and fertilizer on their land. Multiple family wells have tested above the safety standard for nitrates, he says, in part because the wells are shallow and near current or active feedlots.

Families with kids purchased reverse osmosis systems to treat the drinking water. “We all drink that water, and we bathe in it—we’ve got kids,” says Daley. “We’re doing the same things everyone else has to, so it’s a big deal to us.”

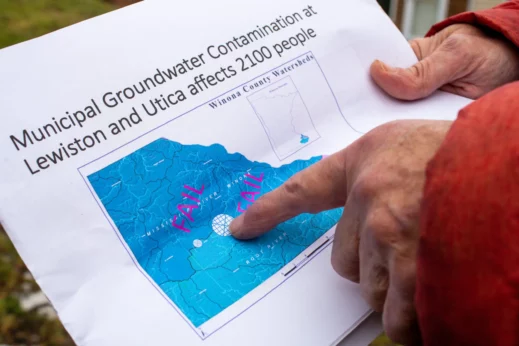

Daley Farm has been scrutinized and protested by environmental groups and government officials as the family seeks to expand its operations to hold 6,000 animal units, well beyond Winona County’s feedlot cap of 1,500 animal units.

Daley says his farm uses cover crops and adheres to fertilizer application guidelines, but protesters have taken issue with the scale of the operation. The operation relies on the cow manure to fertilize the vast majority of the acreage and applies commercial fertilizer only in areas the manure doesn’t reach.

“We’re well above some standards that even environmentalists have asked the state to mandate farmers to do,” he says.

Daley says he advocated for cover crops to be incorporated by other farmers in the area because they’ve been an effective and profitable way to manage nitrogen.

In southeast Minnesota, where Daley and Wotzka live, the land is especially “locally sensitive,” meaning that land use has more of a direct impact on groundwater than in other areas, says Wotzka.

Southeast Minnesota is dominated by Karst geography, where groundwater and surface water are closely connected.

The geography is one reason why the area was selected as a focus of the state’s large-scale testing program.

Wotzka co-founded the Minnesota Well Owners Organization because he sees nonprofits as key players in addressing nitrate contamination. Nonprofits can do “what the government can’t and businesses won’t” do—advocate for public policy to address the root causes of nitrate pollution, he says.

The Minnesota Department of Agriculture is charged with protecting groundwater, but most agricultural practices that would reduce nitrogen runoff are voluntary.

The American Farm Bureau Federation opposes any mandatory “low input methods of farming,” according to the organization’s 2022 Policy Book. Commercial fertilizer is considered an input.

The Minnesota Groundwater Protection Rule, enacted in 2019, was meant to encourage adoption of farming practices that reduce nitrogen runoff. The rule created groups of local farmers, agronomists, government officials and other stakeholders in each Drinking Water Supply Management Area (DWSMA) with nitrate tests showing concentrations of 8 ppm or higher. The groups are charged with encouraging the adoption of nitrogen “best management practices” on 80% of the farmland—excluding soybean acres—within each DWSMA in the next few years.

If, after at least three growing seasons, the 80% target isn’t reached for these higher-risk DWSMAs or if nitrates have continued to increase in the corresponding water supply, MDA can implement mandatory adoption of the best management practices.

A Minnesota Farm Bureau representative says the group is working with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture to develop the best management practices.

“The Minnesota Farm Bureau supports innovative practices such as controlled draining, temporary storage outlet valves and drainage system designs for lowering nitrates,” according to the representative.

The spokesperson also says that the Minnesota Farm Bureau supports “reasonable fees on pesticides and fertilizers, including those used in nonagricultural applications, to partially fund groundwater protection programs.

But Wotzka wants to see the best management practices implemented beyond the DWSMAs, which are focused on municipal water supplies.

He says the nonprofit can also circumvent some of the biases around government programs. Wotzka and Broberg both say thst sharing their personal experiences as well owners helps them build trust with others in similar circumstances.

Wotzka and Broberg view well owners as an underserved class worthy of support. “People in Minnesota are very proud of their water,” says Wotzka. “They’re also very concerned.”

This story was originally published on Investigate Midwest. Investigate Midwest is an independent, nonprofit newsroom. Their mission is to serve the public interest by exposing dangerous and costly practices of influential agricultural corporations and institutions through in-depth and data-driven investigative journalism.Visit them online at www.investigatemidwest.org

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Madison McVan, Investigate Midwest, Modern Farmer

February 2, 2023

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreShare With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.