The Vegetable Gardener’s Guide to Crop Rotation

Try this simple and effective tool to manage pests and boost soil health in your garden.

The Vegetable Gardener’s Guide to Crop Rotation

Try this simple and effective tool to manage pests and boost soil health in your garden.

For larger gardens, beds in rows can be planted by group and rotated, like these bush beans and onions. by Maren Winter, Shutterstock.

There are ways to improve soil health, control diseases and manage pests without applying heavy amounts of fertilizer or pesticides. For gardeners committed to growing several years into the future, crop rotation is one method to utilize.

Crop rotation, a practice widely utilized by farmers, is exactly how it sounds. It involves rotating the planting location of your fruits and vegetables across a sequence of growing seasons. How it works requires an explanation: Plants add just as many nutrients to the soil as they take from it. Rotating the location of crops allows for different nutrients to be distributed throughout your garden from year to year, helping to balance the structure of the soil.

Certain plants can introduce diseases that are soil borne. Even after that crop is harvested, they can remain in the soil. But by removing plants that host certain pests or can introduce a possibility for attracting pathogens the following season, you can help break the cycle and avoid infecting new plants of the same family or variety. Moving crops around can also make it more difficult for overwintering pests to find food when the ground thaws.

It’s important to note that crop rotation is not a one-size-fits-all solution for boosting soil quality or ridding a garden of its diseases and pests. It’s most effective when used in combination with other applications. But there is growing evidence to support that crop rotation helps with soil health and crop yields.

Not sure how to start? Have questions? Not to worry. Follow this guide for an easy transition into the basics of crop rotation.

Organize Your Plants Into Categories

Divide your plants into groups related to their nutrient requirements and outputs. There are differing views on how exactly to do this. We suggest organizing your crops in one of two ways: by category or by plant family.

Rotating By Category

This is best for those who want a beginner option or are working with a smaller space. It involves four categories:

Legumes

Beans, peas, peanuts, lentils, green peas, chickpeas and soybeans.

Roots

Carrots, turnips, onions, beets, radishes and garlic.

Crops that bear fruit

Cucumbers, tomatoes, squash, eggplant, peppers, melons and corn. And a special addition: potatoes. (Potatoes are an exception in this category because they are susceptible to the same diseases as tomatoes, which is why they’ve been added to the fruiting group. If you have problems with potato blight, you will need to separate them out and ensure that you don’t have them follow each other in your rotation.)

Crops grown for leaves or flowers

Leafy greens such as kale and Swiss chard, lettuce, broccoli, cabbage, spinach, Brussels sprouts and herbs.

Rotating By Plant Family

If you’d like to venture out into more specialized territory, we’ve offered a further breakdown by plant family. This is feasible for gardeners with larger spaces or those who have the time to do the research on specific crop nutrient absorption and outputs.

Alliums

Chives, garlic, leeks, onions

Cucurbits

Cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, squash

Brassicas

Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, kohlrabi, radishes, rutabagas, turnips

Legumes

Beans, peas, peanuts

Poaceae (grasses)

Corn

Goosefoot

Beet, spinach, swiss chard

Nightshades

Eggplant, peppers, potatoes, tomatoes

Umbellifers

Carrots, celery, dill, fennel, parsley, parsnips

Map It All Out

Before you get planting, it’s important to understand how your growing space can be used. First, make a list of the crops you’re keen to put into the ground. Then you’re going to want to draw up a diagram of your garden, containers or bed to scale and section off how much space you want to allocate for each crop. Divvy up each area based on crop category.

If you’ve chosen to group your vegetables in the four categories (legumes, roots, crops that bear fruit and crops grown for leaves and flowers) and have a smaller plot of land, you can section it off into quarters. If you’re going the plant family route, divide it into family groups, although they do not have to be equal in size; base it off of the amount in each group you’re planting. We also suggest reviewing our guide to companion planting if you’re sectioning off one area for planting. It will help you determine which crops should and shouldn’t be placed beside each other.

It’s best to avoid slotting plants in locations where you had crops in the same group or family the year before. The further you plant a crop from its previous location, the better. Growers who have the flexibility to dig out a few smaller beds instead of using one large one should consider doing so. This will help separate your groups and allow for smoother, contained rotations that minimize risk of disease spreading or lingering in the soil.

Similarly, raised beds have the advantage of having a physical barrier between different crop families. For those with smaller spaces, using pots or planters is another option to isolate crops and provide additional space for rotation.

Plan Your Crop Rotation Direction

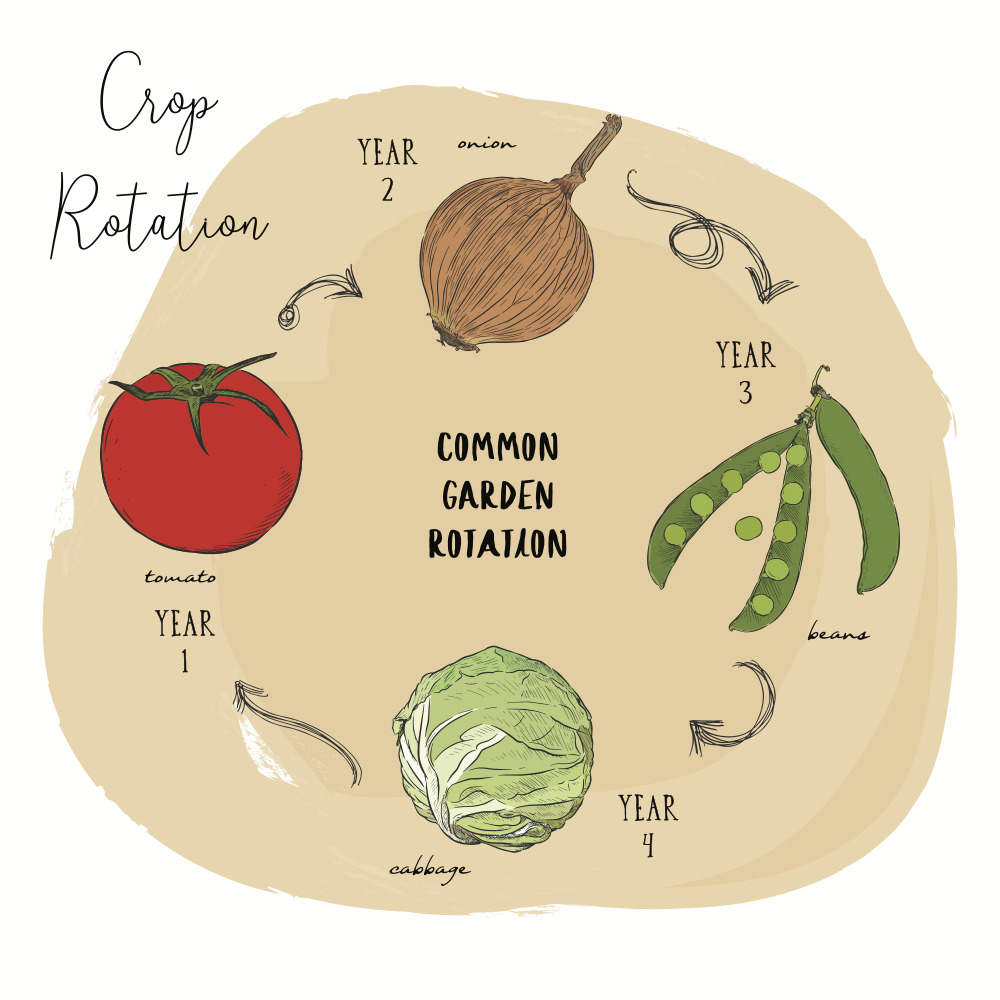

A full crop rotation cycle lasts three to four years. Do not plant an area with crops from the same plant family or group before that cycle is up. Follow these rotation guides, based on your initial categorization of them.

Guide for Rotating By Category

For those who choose to follow groupings by legume, leaf plants, fruiting plants and roots, there’s a formula you can follow for your rotation, which is essentially centered around your legumes as nitrogen producers.

Leaf bearers should take the place of legume crops. This is because leafy crops need nitrogen and legumes are nitrogen fixers.

Your fruiting plants should take the place of your leaf plants. This is because their nitrogen needs are minor and too much can prevent them from producing fruit. The leaf crops should have sucked up enough nitrogen so this won’t be a problem.

Your root plants should take the place of your fruit plants. They need even less nitrogen.

Legumes follow root crops. This is to start the cycle all over again. Legumes also benefit from root crops because they prefer looser soil and root crops will have broken up the soil.

Guide for Rotating By Plant Family

If you decide to branch out and separate your crops based on family, it’s best to understand your crop’s nutrient needs. In addition to a few tips, we’ve indicated certain crops that feed heavily on nutrients versus lightly. It’s suggested that you follow your heavy feeders with light feeders. Nutrient builders or nitrogen fixers can then follow to replenish the soil.

Here are a few tips:

Brassicas are nitrogen hungry, so they can follow your nitrogen fixers, i.e. legumes.

Onions fare well in firmer soil left by those in the brassica family.

Peas and beans like deep, well-dug soil left over from potatoes.

Roots break up the soil, so you can follow them with potatoes, which need to grow in a deeper cavity in the soil.

Corn, tomatoes and cabbage are typically “heavy feeders.” Follow heavy feeders with legume crops to rebuild the soil.

Crops from the Umbelliferae (carrot) family are “light to medium feeders” and can follow any other group.

“Light feeders” include those in the lettuce, onion, squash-family plants as well as potatoes, most bulbs or root vegetables.

Take Stock for Future Years

So you don’t have to go through the trouble of trying to remember what was grown where over the past few years, we suggest keeping your garden maps. It will also help to make note of any pest problems you’ve had in certain areas with specific crops. This tool with University of Minnesota Extension will help you find out what the problem is if you’re unsure.

There are also several digital tools you can use that will provide you with a few pointers for the upcoming season and also track or build a log of what you’ve planted before. This Vegetable Garden Planner is one example. Tomappo is another option for European gardeners—the app even provides personalized assistance in rotations.

If you’re planting in the ground, we recommend conducting a soil test every one to three years. This will help inform any additional soil needs for your plants. We also have a guide for soil testing if you’re unfamiliar with the process.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Lindsay Campbell, Modern Farmer

March 27, 2022

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

I like gardening

Very useful write-up

A lot of very good information. This should be in the 2023 seed catalog that you sell.

I’ve often heard that you shouldn’t plant legumes after garlic or onions, which is conflicting with your advice “Legumes follow root crops” here. I’m now confused. Would you mind elaborating on this further?

I think all these are just theories that don’t work in real application. Why is only nitrogen mentioned as ”soil builder” but phosphorus and potassium are needed as well? And do legumes really prevent plants to bear fruit? I doubt that.

In the text by category, tomatoes are listed as fruit bearing. Onions are listed as Roots.

In the picture of crop rotation, you show fruits following roots.

In the text you state that fruits should follow leaves.

Which one is correct?