Protecting the Timber Industry From the Emerald Ash Borer

The emerald ash borer has destroyed millions of trees. Scientists think that tiny parasitic wasps, which prey on the beetles, hold the key to curbing this invasive species.

Protecting the Timber Industry From the Emerald Ash Borer

The emerald ash borer has destroyed millions of trees. Scientists think that tiny parasitic wasps, which prey on the beetles, hold the key to curbing this invasive species.

The trunk of a dead tree damaged by emerald ash borer insect.by Elena Berd, Shutterstock.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) is a deceptively attractive metallic-green adult beetle with a red abdomen. But few people ever actually see the insect itself—just the trail of destruction it leaves behind under the bark of ash trees.

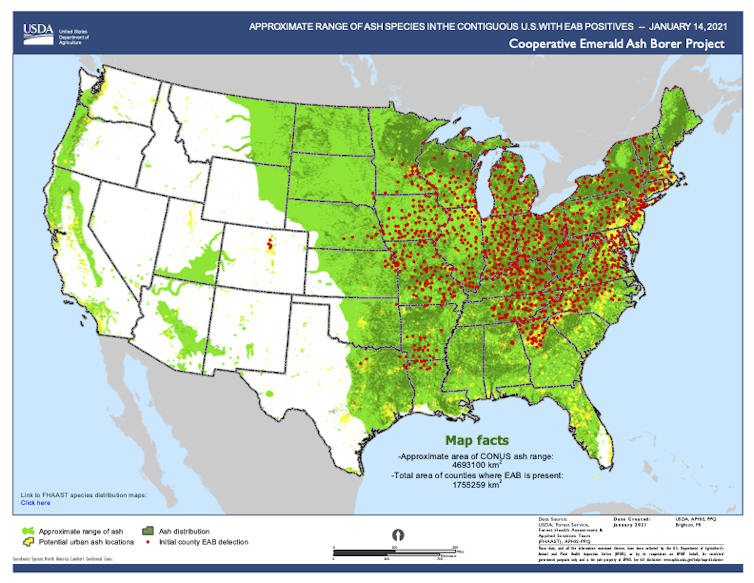

These insects, which are native to Asia and Russia, were first discovered in Michigan in 2002. Since then they have spread to 35 states and become the most destructive and costly invasive wood-boring insect in US history. They have also been detected in the Canadian provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

In 2021 the USDA stopped regulating the movement of ash trees and wood products in infested areas because the beetles spread rapidly despite quarantine efforts. Now federal regulators and researchers are pursuing a different strategy: biological control. Scientists think that tiny parasitic wasps, which prey on emerald ash borers in their native range, hold the key to curbing this invasive species and returning ash trees to North American forests.

I study invasive forest insects and work with the USDA to develop easier ways of raising emerald ash borers and other invasive insects in research laboratories. This work is critical for discovering and testing ways to better manage forest recovery and prevent future outbreaks. But while the emerald ash borer has spread uncontrollably in nature, producing a consistent laboratory supply of these insects is surprisingly challenging—and developing an effective biological control program requires a lot of target insects.

The value of ash trees

Researchers believe the emerald ash borer likely arrived in the US on imported wood packaging material from Asia sometime in the 1990s. The insects lay eggs in the bark crevices of ash trees; when larvae hatch, they tunnel through the bark and feed on the inner layer of the tree. Their impact becomes apparent when the bark is peeled back, revealing dramatic feeding tracks. These channels damage the trees’ vascular tissue—internal networks that transport water and nutrients—and ultimately kill the tree.

Before this invasive pest appeared on the scene, ash trees were particularly popular for residential developments, representing 20-40 percent of planted trees in some Midwestern communities. Emerald ash borers have killed tens of millions of US trees with an estimated replacement cost of $10-25 billion.

Ash wood is also popular for lumber used in furniture, sports equipment and paper, among many other products. The ash timber industry produces over 100 million board feet annually, valued at over $25 billion.

Why quarantines have failed

State and federal agencies have used quarantines to combat the spread of several invasive forest insects, including Asian longhorned beetles and Lymantria dispar, previously known as gypsy moth. This approach seeks to reduce the movement of eggs and young insects hidden in lumber, nursery plants and other wood products. In counties where an invasive species is detected, regulations typically require wood products to be heat-treated, stripped of bark, fumigated or chipped before they can be moved.

The federal emerald ash borer quarantine started with 13 counties in Michigan in 2003 and increased exponentially over time to cover than a quarter of the continental US. Quarantines can be effective when forest insect pests mainly spread through movement of their eggs, hitchhiking long distances when humans transport wood.

However, female emerald ash borers can fly up to 12 miles per day for as long as six weeks after mating. The beetles also are difficult to trap, and typically are not detected until they have been present for three to five years – too late for quarantines to work.

Next option: Wasps

Any biocontrol plan poses concerns about unintended consequences. One notorious example is the introduction of cane toads in Australia in the 1930s to reduce beetles on sugarcane farms. The toads didn’t eat the beetles, but they spread rapidly and ate lots of other species. And their toxins killed predators.

Introducing species for biocontrol is strictly regulated in the US. It can take two to 10 years to demonstrate the effectiveness of potential biocontrol agents, and obtaining a permit for field testing can take two more years. Scientists must demonstrate that the released species specializes on the target pest and has minimal impacts on other species.

Four wasp species from China and Russia that are natural enemies of the emerald ash borer have gone through the approval process for field release. These wasps are parasitoids: They deposit their eggs or larvae into or on another insect, which becomes an unsuspecting food source for the growing parasite. Parasitoids are great candidates for biocontrol because they typically exploit a single host species.

The selected wasps are tiny and don’t sting, but their egg-laying organs can penetrate ash tree bark. And they have specialized sensory abilities to find emerald ash borer larva or eggs to serve as their hosts.

The USDA is working to rear massive numbers of parasitoid wasps in lab facilities by providing lab-grown emerald ash borers as hosts for their eggs. Despite COVID-19 disruptions, the agency produced over 550,000 parasitoids in 2020 and released them at over 240 sites.

The goal is to create self-sustaining field populations of parasitoids that reduce emerald ash borer populations in nature enough to allow replanted ash trees to grow and thrive. Several studies have shown encouraging early results, but securing a future for ash trees will require more time and research.

One hurdle is that emerald ash borers grown in the lab need fresh ash logs and leaves to complete their life cycle. I’m part of a team working to develop an alternative to the time- and cost-intensive process of collecting logs: an artificial diet that the beetle larvae can eat in the lab.

The food must provide the right texture and nutrition. Other leaf-feeding insects readily eat artificial diets made from wheat germ, but species whose larvae digest wood are pickier. In the wild, emerald ash borers only feed on species of ash tree.

In today’s global economy, with people and products moving rapidly around the world, it can be hard to find effective management options when invasive species become established over a large area. But lessons learned from the emerald ash borer will help researchers mobilize quickly when the next forest pest arrives.

Kristine Grayson is an associate professor of biology at the University of Richmond.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Kristine Grayson, Modern Farmer

September 4, 2021

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.