The Current State of Agricultural Education

Once wellsprings of chemical innovation, our nation's colleges and universities are finally rising to meet student demand for a more sustainable future.

The Current State of Agricultural Education

Once wellsprings of chemical innovation, our nation's colleges and universities are finally rising to meet student demand for a more sustainable future.

While overall agricultural enrollment at America’s 75 land-grant universities remained relatively flat between 2004 and 2015, the number of programs devoted to sustainable-farming practices, or “agroecology,” has soared since the USDA started tracking them in 1988.

Most weekday afternoons, Chandler Taylor-Henry, a sophomore at Paul Quinn College in Dallas, heads to the school’s football field, where he plants seedlings, harvests vegetables, and feeds the Wyandotte, Australorp, Araucana, and Rhode Island Red hens. A scoreboard and an old goalpost rise from a blueberry patch in one end zone. Turnips thrive near the fifty-yard line. “This farm is part of what drew me to Paul Quinn,” says Taylor-Henry, who grew up in Jackson, Mississippi.

The historically African American liberal arts college, founded in 1872, does not claim a strong focus on agriculture, or so much as a department devoted to its study. The decision to turn gridiron turf over to the cultivation of organic produce, in 2010, stemmed largely from financial pressures. Facing bankruptcy and a graduation rate of 1 percent, Paul Quinn could no longer justify spending $600,000 a year on a losing football team. The school’s We Over Me Farm has since expanded to occupy four campus acres, generating $40,000 in annual gross revenue (partially from sales to the catering company at the Dallas Cowboys’ stadium). Roughly a quarter of the incoming class of 2017 graduated, and applications – from ambitious students like Taylor-Henry – are up 262 percent from 2010. “My goal,” says the 19-year-old, “is to work at the USDA and help the country get away from unhealthy foods.”

He’s not alone. While overall agricultural enrollment at America’s 75 land-grant universities remained relatively flat between 2004 and 2015, the number of programs devoted to sustainable-farming practices, or “agroecology,” has soared since the USDA started tracking them in 1988. What began as a list of one B.S., at the University of Maine, has evolved to include 256 programs, 97 of those leading to bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. The field has even spawned its own professional organization, the Sustainable Agriculture Education Association, co-founded by Damian Parr in 2006.

Parr, 45, research and education coordinator at the Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), cites student interest as the driving force behind the change. “It’s different from the 1960s, when the young people who cared about these things went back to the land and became vegetarians. Kids today are thinking of how they can insert themselves into food-system institutions and do the work necessary to hold those institutions accountable.” (Full disclosure: Parr and I first met as UCSC undergrads nearly 20 years ago.)

Even at Texas A&M University, once a font of chemical “innovation,” the times are a-changin’. Norman Borlaug – DDT champion, climate-change skeptic, and father of the so-called Green Revolution that ushered in synthetic fertilizers and pesticides during the mid-20th century – served as a prominent A&M faculty member before he passed away in 2009. That same year, a handful of young Aggies established the organic Howdy Farm on campus. And the school is rapidly developing a reputation for research in eco-friendly arenas such as carbon sequestration.

In the 1980s, collapsing commodity-crop prices, record debt, and rising interest rates shuttered thousands of independent family farms – creating a welcome climate for industry-wide consolidation. Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of a nation built upon small, diversified “yeoman” farms gave way to vast oceans of grain and putrid meat-processing plants, employing ex-cons, undocumented immigrants, and others unable to access decent jobs. By decade’s end, enrollment in undergraduate agriculture programs had plummeted some 30 percent. And no wonder. Who’d want to prepare for that future?

The stigma persisted until recently, says Michelle Schroeder-Moreno, an agroecology professor at North Carolina State University (NCSU) in Raleigh. “When I came to NCSU 13 years ago, most farmers I talked to didn’t want their kids to follow in their footsteps. And the kids, of course, could see their parents struggling financially. But now an increasing number of young people want to farm, and farm organically.”

Back in 2005, NCSU’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences only offered a minor in agroecology, and Schroeder-Moreno encountered resistance to the creation of a stand-alone major in sustainable agriculture. “Putting the words sustainable and agriculture together crossed a line in the sand,” she explains. “It implied that all other agriculture was not sustainable.” Finally, in 2015, she got the green light for an undergraduate major in agroecology and sustainable food systems. “Somehow, they were okay with me putting sustainable next to food systems,” says the 43-year-old, who has seen her typical class size grow from 12 to approximately 100 students, half of them women.

Another indicator of progress? NCSU’s six-acre farm, planted in 2008 to provide agroecology students with hands-on experience, currently serves a number of different classes and student clubs. “Even the conventional programs are teaching integrated pest management and cover crops,” Schroeder-Moreno says. “It’s a big step to move beyond the attitude of, ‘Just spray it.’”

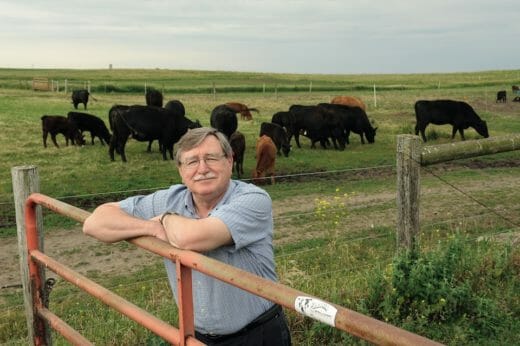

No matter how dedicated the educator, or how hard she or he fights, industrial agriculture often proves a powerful foe. Mark Rasmussen, a tenured professor in the animal science department at Iowa State University (ISU), also functions as the director of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture, established on campus in 1987 by the Iowa Groundwater Protection Act, which funded the center, in part, through a tax on nitrogen fertilizer. “In the late 1980s, coming out of the farm crisis, the planets aligned, and the state chose to address the water-quality problem with this special initiative and tax,” Rasmussen explains. But in May of 2017, Governor Terry Branstad (since appointed U.S. ambassador to China by President Donald Trump) signed legislation redirecting most of those tax dollars to the Iowa Nutrient Research Center, a newer organization at ISU favored by agribusiness interests. As a result, Rasmussen’s annual budget was slashed from over $2 million to $200,000, and his staff reduced from nine employees to two.

Still, he remains optimistic about the big picture, pointing to Iowa State’s thriving 16-year-old graduate program in sustainable agriculture. New facilities are under construction to keep up with the demand, reports Rasmussen, 65. “The defunding of the Leopold Center is an anomaly, contrary to the overall trends in society.”

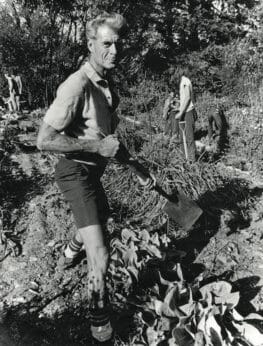

One of the few American universities that can claim deeper roots in sustainable agriculture than Iowa State is the University of California, Santa Cruz. Legendary horticulturist Alan Chadwick first arrived on campus in 1967, transforming a brush-covered hillside into a biodynamic garden – the inspiration for today’s 30-acre organic farm, where 21st-century visionary Damian Parr teaches undergrads much more than vocational practices.

“The food system is fertile ground for deconstructing the forces of oppression – race, class, gender, sexual orientation – that have anchored themselves in American institutions,” Parr says. He encourages students to pursue research projects with real-world social implications, say, how to reform the labor and procurement practices of UCSC’s dining services. Hands-on training in orchard management may open with a lesson in pruning and end with a discussion of farmworker rights at nearby fruit operations.

Parr also aims to overhaul the culturally homogeneous composition of the agroecology program itself. He’s helped develop a new recruitment program that targets high school and community college students from the Latino communities in the Salinas Valley, south of Santa Cruz, with the goal of grooming this more diverse talent pool for graduate-level work and, eventually, faculty positions. “We want minority students to see people that look like them in leadership positions,” he says. “If our enrollment doesn’t reflect the demographics of the state, then we are part of the legacy of oppression and segregation.”

“It’s no accident that we have arrived at this unjust and unsustainable world when we have such an unjust and unsustainable food system,” Parr concludes. “We have learned our way here, and we must learn our way out.”

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Brian Barth, Modern Farmer

January 23, 2018

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

Please send me your Newsletter.

Do you have education system in Canada? I am living at Hamilton