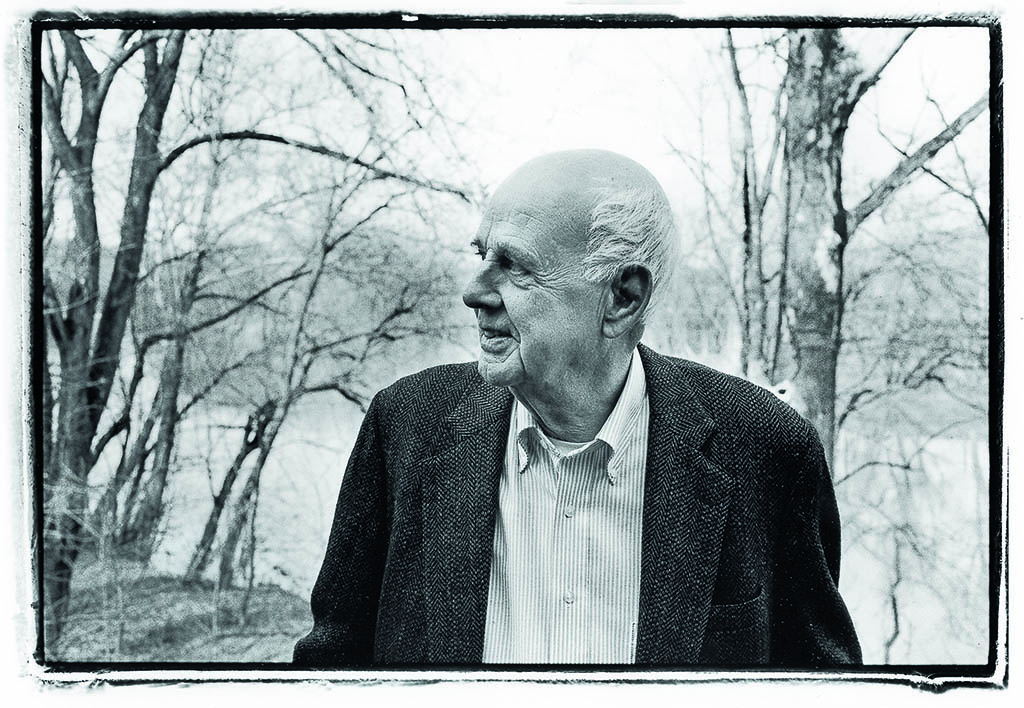

At 83, America's beloved farmer-philosopher still has plenty to say about how our disregard for the past points us in a destructive direction.

WENDELL BERRY CELEBRATED his 83rd birthday in August. He is old. But not so old that he can’t kick and spit and fight every force that threatens to destroy his way of life and, thus, his worldview. “What I stand for is what I stand on,” the seventh-generation Kentucky farmer and urgently prolific scribe wrote in 1980. And, indeed, Berry returns again and again to his hometown of Port Royal (Port William in his fiction). By pledging allegiance to all things local, he has brought global attention to the plight of fragile rural economies and the importance of sustainable agriculture.

In his latest book, The Art of Loading Brush: New Agrarian Writings (available in November from Counterpoint), Berry continues to rage against machines: the laptops and high-tech tractors he believes are causing us to lose touch with each other and our environments. He laments the “dispersed lives of dispersed individuals, commuting and consuming, scattering in every direction every morning, returning at night only to their screens and carryout meals.”

Yes, Berry’s a bit of a curmudgeon, who likens our smartphone obsession to drug addiction and prefers horse-drawn plows to simulated horsepower. He writes longhand before his wife, Tanya, converts the manuscripts on a Royal Standard typewriter. Such anachronistic tendencies, however, point to more than mere nostalgia – namely, a clear-eyed view of the ways in which modern society is wrecking the Earth under the guise of progress. As the journalist David Skinner noted in 2012, “Instead of being at odds with his conscience, he is at odds with his times.”

God willing, the times may have finally swung back around to meet the man. Though Berry would no doubt heap scorn upon today’s $8 heirloom tomatoes and $200 farm-to-table dinners, he did participate in the new documentary Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry, produced by Robert Redford and Nick Offerman. The reluctant subject never shows his face in the film; rather, he shares selections from his work in powerful low-pitched voiceovers. (Visit lookandseefilm.com for information on how to host a screening.) Not coincidentally, the rare photographs on these pages were captured by his intimates: former students and dear friends.

Now, with The Art of Loading Brush, he offers a mix of essays, short stories, and poetry, including the following poem, “What Passes, What Remains.” Part of the author’s Sabbaths series, inspired by long Sunday walks around his Lanes Landing Farm, the verses employ a fictional Port William family, the Rowanberrys, to unfold Berry’s thoughts on mortality and the often heartbreaking ways humans shape the land, and vice versa, over the course of generations.

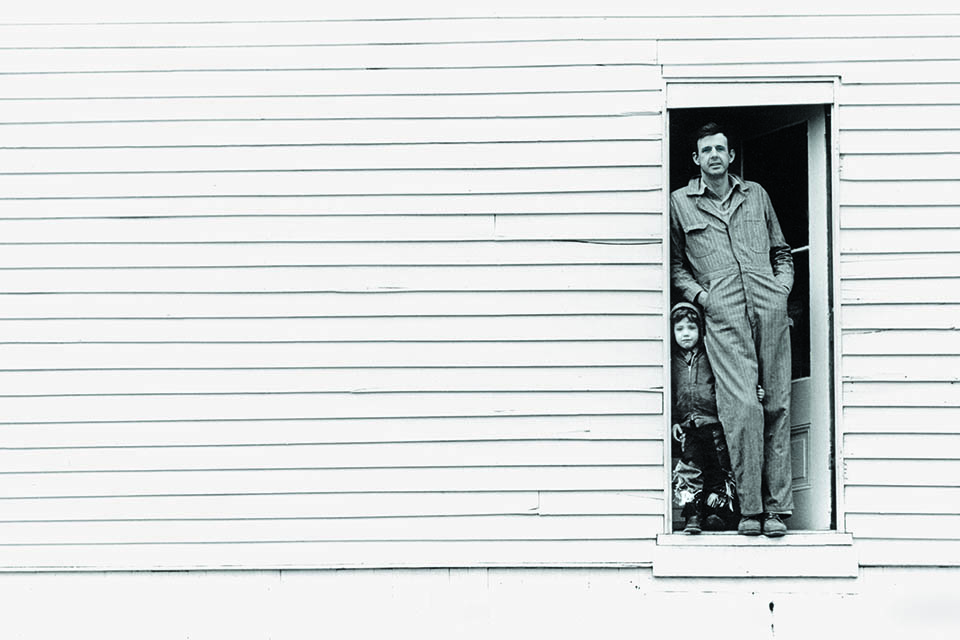

Wendell Berry’s friend – photographer and former Kentucky Poet Laureate James Baker Hall – snapped this portrait of the writer with his son, Den, in the mid-1960s. Den, now 55, and his sister, 59-year-old Mary, represent the eighth generation of their family to farm in Henry County, KY.

{ from Sabbaths 2016”“VIII }

What Passes,What Remains

Here the mingling of the waters

of Shade Branch, Sand Ripple,

the dishonored Kentucky River,

tells the history of our country

which is the history of our people.

Here the mind submits

itself to be shaped, and so

it shapes its thought, partly

of itself, partly of all

in time it has come to know.

Here in this passage of valley

hollowed by the passage of water,

great Life has come in passing

to inhabit every body

inhabiting this place,

giving desire and motion,

giving sight, light,

color, and form, giving

stories, songs, calls,

cries, outcries. How long?

This is the place in which

the living live in the absence

of all who once were here,

their stories kept a while

in memories soon to be gone

the way of the untongued stories

preceding ours, reduced

to graves mostly lost

and a few found strayed

artifacts of stone.

Of those now living here

already few recall

the names of the Rowanberrys

whose home this rough land was

that bears in presence only

their worn ways, some scars

their work made, the well

the early ones dug and walled

where their log house stood

and burned, the disassembled

chimneys, the sundered hearths.

Their numberless disappeared

footsteps are traceable now

only by the remaining few

who remember the last of them.

By love we keep them with us,

and so we have remembered

ourselves as members, gathered

in Love’s household that stands

surpassingly in time: we few

remaining, who keep the stories.

“My lord, they worked hard

for every nickel and dime

they ever had. One crop

finished and gone to market,

they’d start clearing a patch

of hillside for the next crop.

If you look about, you’ll find

their monuments that will last, I reckon,

clean to Judgment Day:

big piles or squared cairns

of rocks turned up by their plows,

dragged out of the furrows,

lifted and put down, and nothing

automatic into it, neither.

Here and there you’ll find

their gullies too, mostly healed

under the young woods about

the age of an old man.”

“I was grubbing bushes

and sprouts with an axe, setting

my own pace, but hard at it.

Art and Mart were felling

and logging up the trees

with a two-man crosscut saw.

After while Mart said, ‘Pascal,

I’ll rest you a little. Let me

run that axe, and you

get here on the saw with Art.’

So we traded, and good God!

I felt like I had a hold

of the tail of a stout big calf

and couldn’t turn loose. Even

what they called rest was work.

And Mr. Early Rowanberry

– the old man, but not so old

then as I thought – he

would be working always, always

somewhere ahead of them.”

Berry eschews modern tractors in favor of draft horses, which he has employed for plowing, hauling firewood, and, on this 1960s occasion, taking neighbors for a ride.

“He come in there at Burgess’s

one evening late, a bunch

of us loafing there, talking,

the way we’d do. He bought

a steel-beam rounder plow,

paid in cash, and then

did what not a one of us

foresaw. He’d come walking.

It was a heavy plow. Somebody

would have hauled it down there

for him in a day or two.

He picked it up by the beam of it

and laid it over his shoulder

like it wasn’t more than a hoe,

hunched it into place,

and set off home on the path

down Shade Branch, a mile

to walk and it getting dark.

Lord amighty! Hurrying

to be ready to work in the morning,

I reckon. No time to lose.”

“Oh, it hurts me to remember

how hard my daddy worked.”

And she by then was old

after a life of her own

hard work, hers and Pascal’s,

by which they bought, paid for,

and improved their farm, built

and paid for a good small house.

Theirs had been a time

kinder to them than her father’s

had been to him. Their life

even so had been in its way

a triumph of work and thrift,

care and self-respect.

Whoever knew them knew

something inarguably good.

Photographer David Peterson accompanied Berry to an Omaha rally in August 1986, amid the “farm crisis” that pushed many small producers into foreclosure. The embroidered message on this protester’s shirt says it all.

“A while after we got married

and set up housekeeping

over across the river,

knowing she missed her folks,

I brought Sudie back home

for a visit late that winter.

It sleeted during the night.

In the morning all outdoors

was coated with ice. They’d been

cleaning up another

hillside for another crop:

felling the trees, grubbing

out the bushes, closing in

on a great big snarl of briars

still in the way. After

breakfast, Mr. Rowanberry

sent us boys to the barn,

slipping and sliding on the ice,

to do the chores. And he

took down his scythe from its nail

and went to the hillside to mow

that big blackberry patch

before the day warmed up

and melted off the ice

from the catclaws of the briars.”

And so some days they were favored,

when place and work and weather

seemed to answer one another,

when what the world asked

and what they gave seemed

almost in rhyme, hour

after hour, daylight to dark,

days too when the world asked

for all they had to give

and more, when a boy, under

the demand of a father, brittled

and driven, could wish to be

some place he could not go.

During the 1973 tobacco harvest, Berry (center) and his daughter, Mary (right), help hang freshly picked leaves to dry at their neighbor Loyce Flood’s farm.

“My daddy remembered Art Rowanberry

disking ground with a team of mules

when he wasn’t more than eight years old.

His feet didn’t reach to the frame of the harrow,

and his daddy had tied him onto the seat

with a little piece of cotton rope.

He was all the help his daddy had.

I don’t reckon Art remembered

when he didn’t know how to drive a team.”

“Art enlisted in the army in ’42

when he was thirty-seven years old.

In basic training he rested up.

He said he gained a little weight.”

“To stand around waiting to work,

that was something I had to learn.

One day they give us out some axes,

thick as your foot, dull as a froe.

I taken a file and whetted mine

to where it was some account. Them boys

just stood around and watched me chop.”

“He was the oldest, the eldest son.

He thought if he went, the younger ones

would be spared. But they drafted two of them.

If he hadn’t enlisted, Art might not

have had to go. But oh my!

He saw a world he’d never dreamed of,

and dreamed of, I reckon, the rest of his life.”

“I stopped in Bastogne with a buddy of mine

and we bought us a big plate of potatoes.

We still were eating them when the Germans

cut us off. Before that was done with

we needed a big plate of potatoes.

We was hungry, down to just

one little pancake a day.”

I said, “I reckon you all were glad

when they broke through and got you out.”

And he said, seeming to look and see it

again through almost forty years,

“We was glad to see that day when it come.”

“It was during the war, I reckon.

I don’t remember why,

but I was mowing weeds

with an old machine we had

and my good team of mules.

The weeds was tall as the mules

and it was smothering hot,

punishing hot, the air

flying full of chaff

and biting flies. And that

old leftover machine,

you had to run it fast

to make it cut atall.

I hit a stump and broke

the cutter bar clean off.

I never was as glad

of anything in my life”

– Mart.

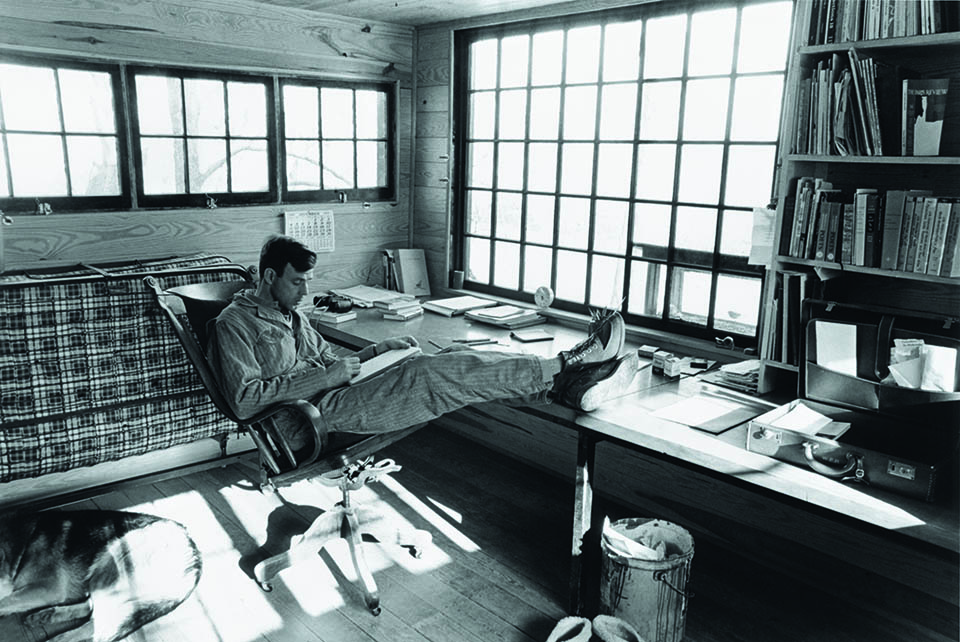

This 1966 shot captures Berry at his writing desk, which sits in front of the 40-pane window that sparked his Window Poems. It also inspired the title of the recent documentary Look & See.

Or any of them,

at work in the hot sun,

might have looked into the woods

at the trees standing in shade

at ease and quiet, and thought

again that man must earn

his bread by the sweat of his face.

Mart, who here stands

imperfect as he knew he was,

was rightly somewhat glad

that when the Reckoning came

and he stood before his Maker

he would at least have met

the terms of our condition, discharged

his debt, his account of sweat

and labor paid in full.

At last, when we’d worked together,

through the morning, and Flora

asked, as we came into the kitchen

for dinner, glad to see him

as she always was, “How’re you,

Art?” Art said, “Well,

they say you’re once a man

and twice a child, and I believe

I’ve been through just about

all them possibilities.”

Now they and all their days

are gone into the silence

and invisibility that come

with an old man’s gathered years

to hover over the home,

the known, land. None

like them will ever live

in such a time as theirs

in such a place as this

place was in their time.

Eternal in its passing, Life

came to them, offering its gifts,

making its demands, and they

answered by their work, their pleasure,

their enduring, knowing at times

a timelessness in which

they woke as living souls.

To one who has watched and remembered,

listened and remembered, in time

sharing the work and the weather,

the laughter and the grief, it seems

that Life is with us always

as a wide wind passing

through the woods, moving

moving every leaf. As it gives us

our lives and then, as we

have made them, takes them away,

a fitting care remains

as ever still and whole

in our great Taskmaster’s eye.

Berry’s neighbor Loyce Flood rides into her tobacco fields in 1973.

I was recently in Louisville, Kentucky where I lived until the age of 28. I have lived in Buffalo, NY since and now am 77 years old.

While in Louisville, I bought a copy of Sabbaths 2016, Wendell Berry. I love it.

Wonderful account of lives lived, work done, values shared and satisfaction accomplished. Thank you.

Tx u