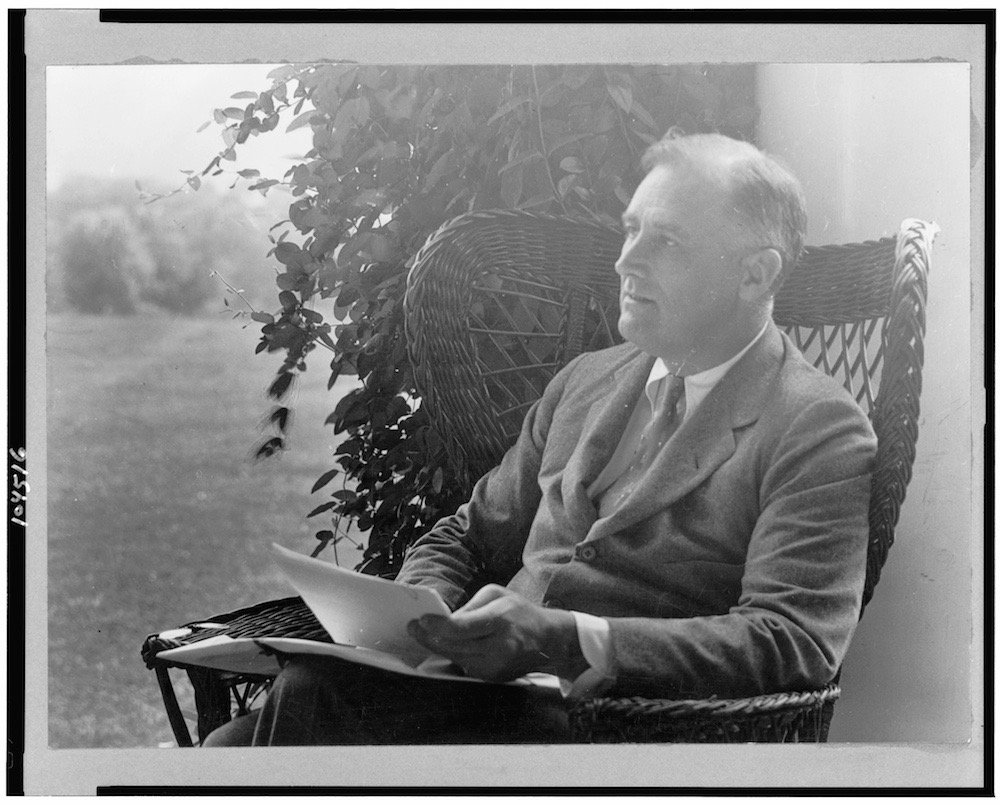

The brutal killing of a dairy farming family in November 1930 shocked the nation and forced future U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to intervene. Ninety years later, the murders remain unsolved.

Thanksgiving Day, 1930

Bernice Germond stepped off the bus near her family’s farm on the outskirts of Stanfordville, a small town in New York’s Dutchess County, about 90 miles north of New York City. The 18-year-old was returning home for Thanksgiving from Poughkeepsie, the county seat, where she was attending business school. The bus dropped her off just after 5 p.m., November 26, 1930, and it was already beginning to get dark. She wished the driver a happy Thanksgiving, but then noticed something strange about her parents’ house, which she could see from the road.

“Looks like nobody’s home. The house is dark,” Bernice commented, a bit perplexed. She then made her way to the farm as the bus pulled away. It was the last time she was seen alive.

Two Days Later

It wasn’t like James “Husted” Germond to fail to deliver his milk to the Borden Company dairy. He hadn’t shown up on Thanksgiving, which was unusual enough for the employees to comment on. But when he again failed to appear, Willard Coons, a Borden employee, was sent to the farm to make sure everything was all right.

Coons arrived just after 9:00 a.m. Not seeing anyone in the yard, he got out of his car and began poking around. He heard the hum of the milking machine and the lowing of the cows and found the herd in the barn in bad need of milking. “Hello?” he shouted as he walked toward the wagon shed. No one answered. The door was ajar, and as Coons stepped up to the doorway, he saw them. Husted and his ten-year-old son, Raymond, were inside the shed. The pair was soaked in blood from numerous stab wounds covering their bodies. Inside the house, Mabel, Husted’s 47-year-old wife, was lying on the kitchen floor near the stove. She, too, had been stabbed multiple times. Bernice’s body, a pincushion of stab wounds, was found near her mother’s body, under the kitchen table.

A map of Standfordville, where the murders of the entire Germond family took place in 1930. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The Crime Scene

A short time later, the Germond farm was a hive of activity as members of the Dutchess County Sheriff’s Department and the state police tried to make sense of the brutal murder that would be billed by the press as the worst crime in the county’s history. It didn’t take long for an army of reporters and nosy neighbors to show up and disturb the crime scene, which was already failing to provide much in the way of clues. The discovery of a large butcher knife that had been wiped clean of any prints provided the first solid piece of evidence in the case. Investigators were able to trace where it had been purchased, but this eventually led to a dead end, as the shopkeeper was unable to identify the person who bought the knife.

This would be the first in a series of stumbling blocks that stymied the murder investigation. The police were long on theories and short on facts. Husted was a mild-mannered, struggling dairy farmer who attended church regularly and was a member of the local Grange. He didn’t seem to have any enemies. Among the many working theories the investigators pursued was one about a mysterious stranger who had allegedly been seen walking near the Germond farm around the time of the killings. The suspect, Florentine Eirmendi, was eventually picked up in a Brooklyn pool hall by New York City police and hauled upstate.

He was released after none of the witnesses who had claimed to have seen him walking near the farm could pick him out of a lineup. Other leads went nowhere, including long-shot theories about a vengeful suitor of Bernice; disgruntled hunters who had been fined after being caught hunting near the farm; and an angered road worker who had been fired for making a pass at Bernice. None of these leads panned out.

On a bitterly cold day in early December, the Germond family was laid to rest. The investigators continued to chase down tips in a case that had gained national notoriety, then stalled and became a hot-button political issue. The authorities offered a $25,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the killer without result.

It was around this time that Governor Roosevelt, who was from Dutchess County, stepped in at the behest of several prominent local residents who were dissatisfied with the handling of the case. He ordered the state’s attorney general to take over the investigation. The Dutchess County DA, John R. Schwartz – a Republican running for reelection – believed the move was politically motivated. The chairman of the county Republicans, Frederic H. Bontecou went even further in his assessment of Roosevelt’s decision, calling the governor’s meddling “mean and picayune politics and merely a move to get votes.”

A Suspect Is Charged

It wasn’t until February 1933, more than two years after the murders, that Sheriff Oakleigh Cookingham was able to make a case against the Germond’s neighbor, Arthur Curry, a 46-year-old with a violent history, who Cookingham had come to believe was behind the killings.

Curry had served time for assault and had an explosive temper. He was a chicken farmer, barber, and roadhouse operator – and possibly a small-time bootlegger. Investigators learned that on the day of the murders, Curry had told his wife he was heading over to see Husted about some money he was owed. He came back around 6:30 p.m., within the time frame of when the murders took place. He later told his wife that he’d seen Husted that day but hadn’t been able to collect what he was owed. Cookingham’s case against Curry was circumstantial and on the weaker side, but the sheriff pressed ahead anyway. On March 9, 1933, Curry was charged with the murders, but it didn’t take long for his defense lawyer to seek a dismissal of the case for lack of evidence. A hearing was held in Poughkeepsie on April 3. It didn’t go well for the prosecution.

Cookingham told the judge that he believed the killings stemmed from a quarrel over hunting rights. Germond had refused to allow Curry to hunt on land he’d leased from him, leading to a blowup with devastating consequences. “Our investigation shows that the murders were the acts of a quick-tempered man after an argument,” the sheriff told the court. The judge, siding with the defense, ordered Curry released and the charges dismissed, telling the sheriff the case was made up of “too much suspicion and too little evidence.”

By this time Roosevelt had been elected president and his interest in the case had faded, as did that of the media, and eventually the public interest. Curry died in 1955, taking whatever he knew about the case – if anything – to the grave. The case remains unsolved today.

This story is adapted from Andrew Amelinckx‘s newest book, “Hudson Valley Murder & Mayhem” by The History Press.

You have some facts wrong in the Germonf case. I have just completed my 120 report on the case for the Futchess County Sheriffs Office. I am the only qualified person to have seen all the evidence in the DAs office county records and autopsy reports and inquest minutes

Please make formal request by email for a copy of this report

Regards

Vincent P. Cookingham, Ph.D

Retired Forensic Scientist