In the far reaches of Norway, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault acts as an insurance policy against worst-case scenarios by securing the building blocks of our planet's food supply.

“VISIBILITY WAS LOW, winds were high, and the plane was bouncing and rocking about as it threaded its way through the mountain passes.” So writes agricultural evangelist Cary Fowler in the new book Seeds on Ice, about his initial 2004 visit to the Norwegian island where he ultimately helped establish the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. After two attempts to land, the pilot informed his passengers that he didn’t have enough fuel to try again. “My first trip to Svalbard ended without ever setting foot on it,” Fowler continues. “It was not an auspicious beginning.”

But the Tennessee native, who was given six months to live after being diagnosed with skin cancer four decades ago, isn’t a man who gives up easily. Not only would the now-67-year-old succeed in landing on Svalbard, he’d find a way to surmount the myriad challenges – political, technical, financial – involved in founding the first global seed bank, charged with no less a task than safeguarding the future of humanity.

Four years after that failed descent, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault officially opened for business. The fail-safe structure now houses seed samples from nearly 900,000 varieties of crops (more than half the estimated 1.5 million on the planet), ensuring that the genetic material critical for sustaining us remains protected, regardless of war, natural disaster, rapidly evolving pathogens and pests, and climate change. The seeds are stored at 0°F behind multiple locked doors, further secured by cameras, alarms, and motion-, fire-, and gas-detectors. The facility, financed by the country of Norway and managed by the Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen), holds its collection “in trust” for the international community. Storage is free to depositors – mostly agricultural research centers and national gene banks – who retain ownership of their seeds.

Already, there’s been one withdrawal. As civil war broke out in Syria, the Aleppo-based International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) submitted 116,000 varieties of wheat, barley, chickpeas, lentils, and other crops for safekeeping beneath the ice. In September 2015, with ICARDA’s former headquarters in the hands of opposition forces, the organization accessed a portion of its samples, so that researchers in Morocco and Lebanon could reestablish them for future generations.

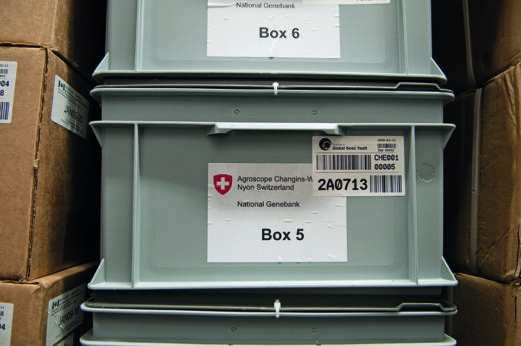

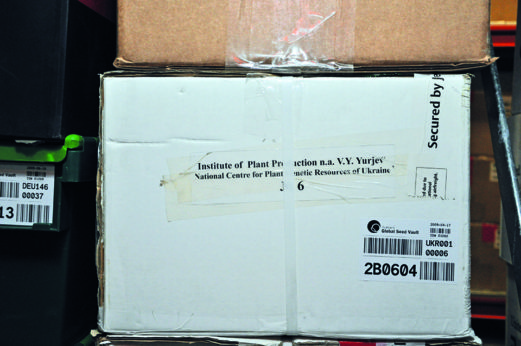

GALLERY ABOVE: Most depositors – agricultural organizations the world over – pack seeds in moisture-proof, airtight foil envelopes (fourth row, center) before sending them to Svalbard. Upon arrival at the vault, each box is affixed with a bar code that tracks precisely where the submissions are stored.

The vault now houses seed samples from nearly 900,00 varieties of crops, more than half the estimated 1.5 million on the planet, ensuring that the genetic material critical for sustaining us remains protected.

During construction, in 2007, the crew installed supplemental cooling units to quickly bring the facility’s temperature down to ”“18°C (roughly 0°F), ideal for long-term seed storage.

Shot in late September, this photograph of the Advent Valley – visible from the seed vault’s door – shows an extreme version

of dusk. In a few weeks, the sun will not rise above the horizon for months, a phenomenon known as “polar night.”