To meet the demand for cheap pork, large-scale producers argue they must cut corners on animal welfare. One major company begs to differ.

Before entering New Hope, a 5,000-sow farm in south-central Pennsylvania, I was ordered to strip. Off came everything, including my hearing aids. Buck naked, I showered and shampooed, then pulled on freshly laundered socks, underpants, and overalls provided by the farm. I had encountered similar biosecurity protocols, intended to prevent the spread of disease, when visiting massive concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the past. But I expected this place to be different.

Overseen by Clemens Food Group, a pork company headquartered near Philadelphia, New Hope represents one of four Pennsylvania farms that house the female pigs who give birth to piglets who will ultimately become dinner for customers of Clemens’ Farm Promise brand. Though far from pasture-raised perfection, these farms aim to produce pork affordably, on a large scale, without sacrificing animal welfare. No less an authority than Josh Balk, senior director of food policy for the Humane Society of the United States and a strident critic of factory livestock farming, calls Clemens Food Group “the leaders in the pork industry.”

The most intelligent farm animals by a mile, pigs possess the mental capacity of 3-year-old children.

Typical factory pig farms confine each sow to one crate when pregnant, then another for birthing and nursing. Given the rate of reproduction (a litter every five months, despite a four-month gestation period) these animals often spend their entire lives in metal cages not much larger than human coffins. Beyond eating and drinking, a crated sow exercises virtually none of her natural impulses. No rooting, no walking, no gathering straw to build nests. Many can’t turn around or take a single step, and develop hoof and leg deformities. Others suffer from open, oozing sores where their fleshy rumps and shoulders press against the cages’ steel bars. Some literally go insane, frantically biting the bars until their lips and gums bleed.

Think about that the next time you score pork chops for $4 a pound. The most intelligent farm animals by a mile, pigs possess the mental capacity of 3-year-old children, according to researchers at the University of Cambridge Veterinary School in England. Yet the need for efficiency encourages the CAFO model: 80 percent of American sows are crated constantly, to prevent 400-pound mothers from accidentally crushing their 3-pound newborns or injuring each other while fighting for food. Almost immediately after weaning one litter, these female pigs will be artificially inseminated with the next. (A few “teaser boars,” also caged, merely supply the sexual odors necessary to bring the gals into heat.)

New Hope’s piglets are still separated from their mothers, who nurse through crate bars, which keep the 400-pound sows from accidentally crushing the 3-pound babies.

As New Hope’s manager, Bethel “Pidge” Ash, handed me rubber boots and escorted me to a birthing, or “farrowing,” room, I wished she’d supplied a gas mask, too. The air in the room, containing more than 700 piglets and 60 sows, crammed inside metal crates, was thick with the stench of ammonia and dung. So far, New Hope smelled and looked an awful lot like a factory pig farm I had toured a few years ago in Iowa.

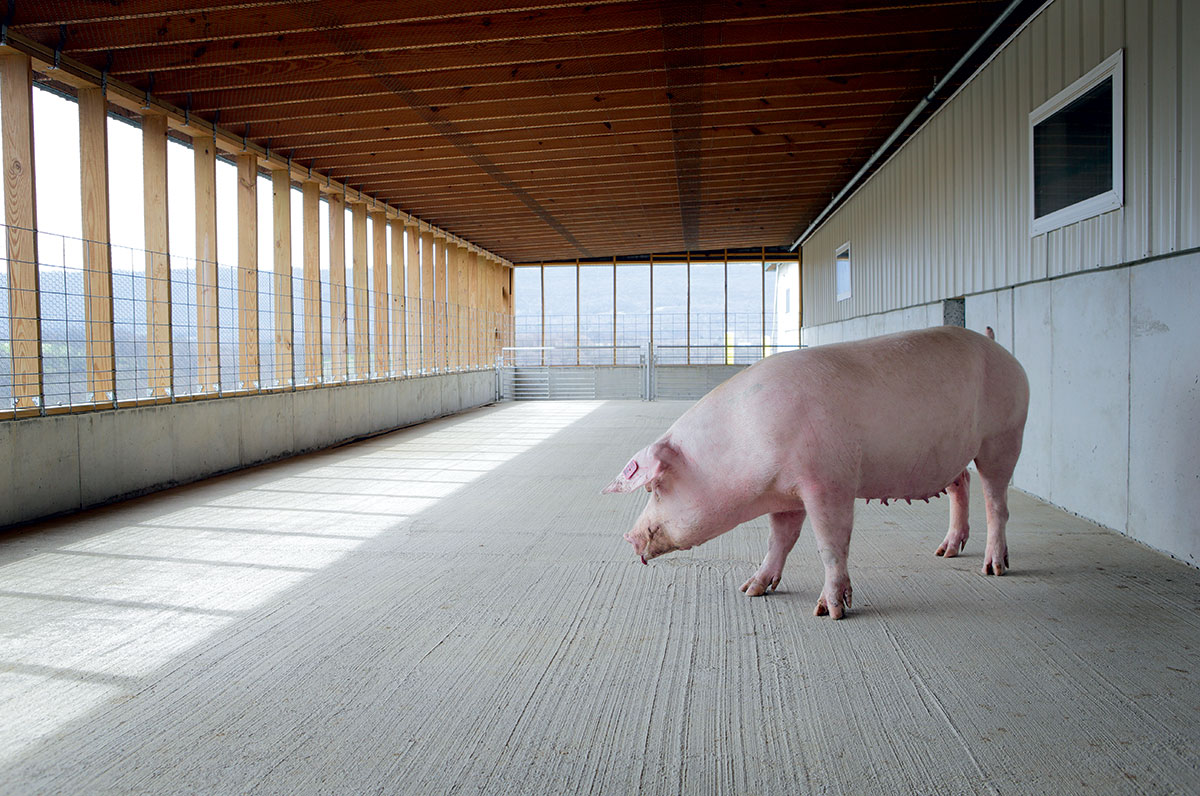

I sealed my nostrils and followed Ash down a long hallway lined with similar farrowing rooms. Finally, at the end of the hall, she revealed a massive space divided into pens the size of volleyball courts. Instead of wall-to-wall crates, each pen offered about 70 sows the option of snoozing in open stalls or roaming free in a central zone. There, pigs meandered about, occasionally taking a few trotting paces, activating water fountains, nipping sections of plastic piping tied to the edges of the stalls as toys, and probing Ash and me with their twitching snouts. When one sow approached a tunnel-like feeding station, its door automatically retracted. Ash explained that the pigs’ ear tags incorporate micro transmitters. If a given sow hasn’t eaten her daily rations, a computerized system grants access, then shuts the door to prevent others from entering and fighting her for food.

The system also allows Ash and her colleagues to monitor the pigs from handheld devices. “At a glance, I can see that she’s already eaten today,” Ash said, “and that she’s consumed her exact allotment of food.” The technology tells Ash when a sow is expected to give birth and alerts her if a New Hope employee has identified a possible health problem. The ultimate benefit of this open-housing arrangement: The pigs at New Hope spend only around 75 days a year in farrowing and gestation crates – as opposed to the usual 365.

A sow activates one of the farm’s high-tech water fountains.

Each sow has an ear tag that grants daily access to feeding stations – one pig at a time, to prevent food fights.

So how did Clemens Food Group, the 13th-largest domestic pork producer, come to adopt its animal-forward practices? Our nation’s Humane Society deserves some credit. Thanks to the nonprofit’s consumer-education efforts, a number of states have passed legislation limiting the use of crates. And more than 100 corporations, including McDonald’s and Costco, have pledged to source pork only from producers that eliminate full-time crating. Robert Ruth, who manages Clemens’ Farm Promise brand, had also noted the high-tech pig-farming methods gaining steam in Europe. “We’re always interested in trying new approaches,” he says, “so long as they’re financially viable and improve the care of our animals.”

More than 100 corporations have pledged to source pork only from producers that eliminate full-time crating.

Another Farm Promise operation in Pennsylvania, Willow Hill, is currently experimenting with innovative stalls that further reduce total annual crate time to 33 days. Although Ruth hopes to implement these stalls across the brand, the managers at Willow Hill continue to confront unacceptable piglet mortality rates. “It’s not ready for prime time,” Ruth admits. “But we’ll get there.” Already the farm has added a screened “pig porch” that affords sows a somewhat outdoorsy experience.

Willow Hill and New Hope (along with the other sow farms, Van Blarcom and Sullivan, that supply Farm Promise) don’t begin to resemble hog heaven. The pigs spend most of their lives inside on hard flooring. Had I not seen typical factory hog barns firsthand, I might have been appalled. “Crates are horrendous,” says the Humane Society’s Josh Balk. “They should never be used. But we’re trying to reduce and eventually eliminate the confinement of sows in crates as quickly and pragmatically as possible.”

A quick scan of each sow’s ear tag reveals vital information, such as whether she’s eaten that day and when she’s expected to give birth.

On the same day I hit New Hope and Willow Hill, Maisie Ganzler was checking out the facilities. Ganzler serves as the chief strategy and brand officer of Bon Appétit Management Company, a $1 billion food-service outfit that provides meals for universities, museums, and businesses, including Google, the Getty Center, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Though Bon Appétit (not connected to the magazine of the same name) maintains the highest standards of animal welfare possible, Ganzler recognizes that pasture-raised operations can’t meet her employer’s demand for nearly 3 million pounds of pork annually.

Last year, she agreed to buy as much meat as possible from Clemens. “We’re paying more for the product, but it’s a price we can afford,” she says. “To be clear, this is industrial pork, and while that’s not a romantic picture, we’re excited to see crates being used so minimally. Clemens shows other big companies that it can be done.”

Between clients like Bon Appétit and the ShopRite grocery chain, with 260 stores, Ruth faces a problem he never dreamed of when he decided to explore more humane practices: keeping up with demand. To do so, he and his employer hope to increase Farm Promise’s production fourfold in the next three years.

Ideal? Hardly. But as Balk pointed out to me, every step an uncrated sow takes is a step in the right direction.

Like New Hope, Willow Hill Farm is also in Pennsylvania and operated by the Clemens Food Group. One advantage here: a screened “pig porch.”

Barry Estabrook is the author of Tomatoland and Pig Tales.

Thank you for caring. All companies should have to do this.

Also want to start apiggery unit but ineed some ideas

Good going!!

Please, help me get pig farm wellfare desgining for scale 600 sows

Good piggry, I want to start up my own pig farm. So I need ideas on how to go about it thanks

Hi guys. Am Joseph I have working on pig farming-for past six moth now I have seen som improvement in my work in your help

Good piggery ideas required

for more production,good pigery units are required

I am exploring pig farming and I am in the process of researching as much as possible in order to ensure that I produce a great product from a well looked after animal. I do believe in my heart (this might not be scientifically true) that this improves the quality of the meat. This article has been helpful. Thank you.

This is wan of my work. I need more help guys