The experts who comprise the USDA's Extension System work tirelessly to assist farmers and gardeners from coast to coast, yet rarely receive recognition. Until now.

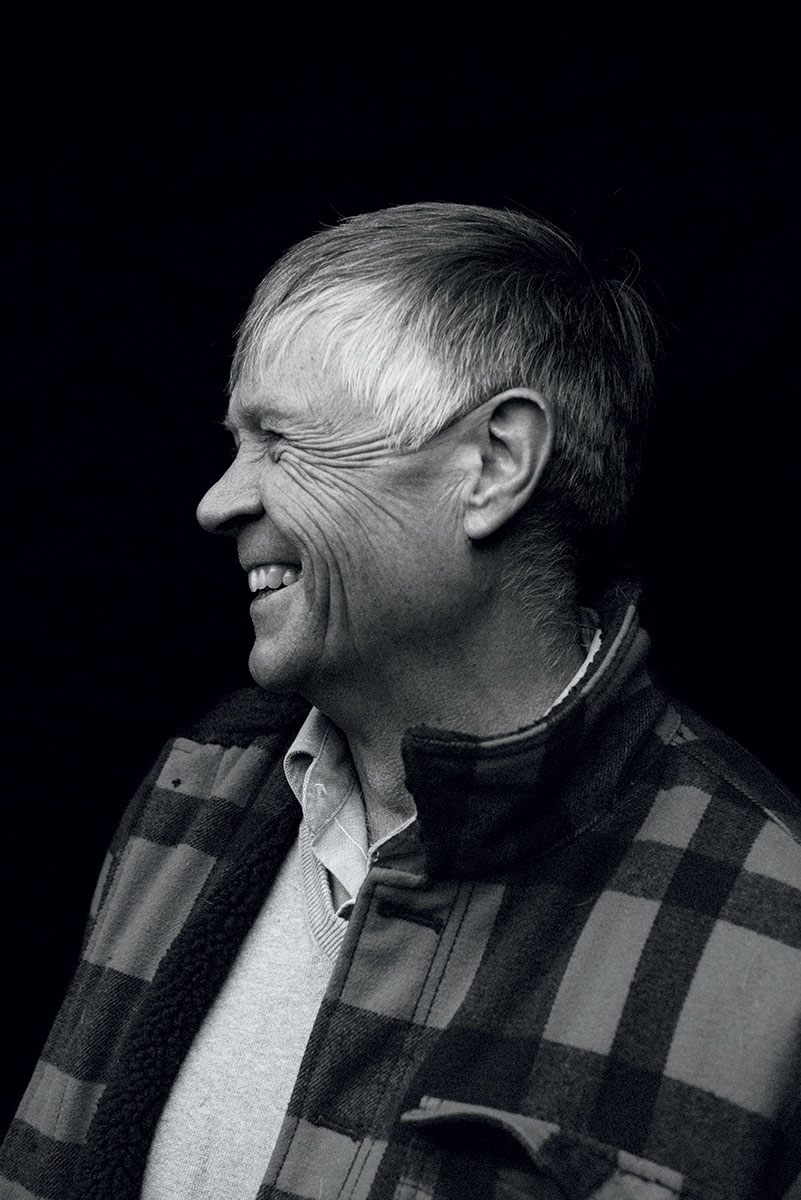

In 1914, when the United States government established the Cooperative Extension System, about one-third of Americans farmed full-time. Today, only 2 percent earn a living from the land. But the federal service’s cadre of agricultural experts, called extension agents, is still some 14,000 strong. Based in (primarily public) universities throughout the nation, these horticulturists, livestock specialists, and conservationists offer services – soil tests, pathogen diagnostics, on-site consultations – for fees that range from nominal to nil. The pros also deliver advice tailored to the local communities they serve, in terms of both the political and environmental climates. I know this firsthand. As a veteran Vermont farmer, I’ve relied on my extension agent for decades. To show Ann Hazelrigg (pictured above), and her equally capable colleagues, some long-overdue gratitude, I asked Modern Farmer‘s online audience to nominate standout agents in their regions. The resulting seven profiles, starting with my ode to Ann, salute the people who just might be the most important, least celebrated civil servants in the United States.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Ann Hazelrigg[/mf_h2]

Burlington, Vermont

University of Vermont

Years with extension: 34

When an entire section of blueberries on my farm withered and died, Ann Hazelrigg identified the cause as drowned roots. She diagnosed the soil-borne fungus attacking my tomatoes and prescribed crop rotation. Each time I encounter a sick plant, Hazelrigg suggests I send it to her, roots and all, or visits my farm to observe the issue in person – and swears she doesn’t mind. “I would not want to be stuck in a lab all day,” demurs the 61-year-old,who recently received her Ph.D. in plant and soil science from the University of Vermont.

As director of the school’s Plant Diagnostic Clinic, Hazelrigg solves some 500 horticultural mysteries each year. During the growing season, she and her co-workers send out bimonthly emails, keeping us Green Mountain State growers apprised of, say, an onslaught of late blight or the dreaded spotted wing drosophila. Even after three decades with the extension service, Hazelrigg remains humble. “I’m still learning,” she insists, pointing to cases far freakier than mine. “Once, I had a state trooper come in with a pile of branches, wanting to know if they were native.” Her ID of the greenery, which had covered a dead body, aided in the murder investigation. She has also germinated seeds brought in by cops who suspected they were marijuana.

Her CSI talents aside, Ann Hazelrigg is, first and foremost, a farmer’s friend. I know that she’s got my back. I hate having to call Ann, but I always enjoy seeing her.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Ray Benson[/mf_h2]

Mississippi County, Arkansas

University of Arkansas

Years with extension: 6

Most of the farms under Ray Benson’s purview turn out commodity crops like corn, soybeans, and cotton. His aim: to help big ag leave a smaller environmental footprint. Benson, who studied agronomy and crop science as a University of Arkansas grad student, advocates for technology that helps area farmers monitor and, ultimately, reduce the amount of water, fertilizer, and pesticides used in their fields.

Some embrace the changes. David Wildly has adopted a number of Benson’s recommendations on his 80-year-old family farm, which encompasses some 12,000 acres of wheat, peanuts, and other crops. Among them: installing irrigation surge valves. “I can’t say that we’ve stopped wasting water 100 percent,” Wildly admits, “but we’re conserving quite a bit.”

For the more skeptical types, Benson coordinates on-site side-by-side demonstrations. In one area, pesticides, fertilizer, and water are applied according to the monitor-ing equipment’s data, while another gets a traditional schedule of amendments. Benson finds that the increased yields and end-of-season spreadsheets speak for themselves.

“I’d like to take steps now, so when our grand-kids want to farm, there are still adequate natural resources,” says the 48-year-old.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Monica Cooper[/mf_h2]

Napa, California

University of California

Years with extension: 7

Monica Cooper’s first year as an extension agent, 2009, was trial-by-fire. Or, rather, trial by Lobesia botrana. A routine check of a local vineyard for invasive mealy bugs revealed the presence of the incredibly destructive Mediterranean caterpillar that, until that moment, had never been seen in the United States.

“I’d been on the job exactly five months,” Cooper remembers. A graduate of the University of Florida with a degree in plant health (and, luckily, an emphasis on pest management), she possessed the know-how. “But I had to learn, quickly, to balance the scientific research with the needs of local growers and the massive media attention.” Cooper, whose region comprises roughly 600 grape growers and 48,000 vineyard acres, has since become a forensic pro, able to determine if the culprit is fungal, multi-legged, or weather-related: “When the vines aren’t performing well and farmers don’t know why, they come to me.” Mayacamas Olds, the director of operations at Huneeus Vineyards, is one of those seeking her advice. “Monica helps me work through all sorts of stuff, like controlling leaf-roll infections,” Olds says. “She always brings the right people to the table.”

Cooper also proves an adept gatekeeper. She fields near-constant requests from people in California’s tech industry eager to try out a new drone or mapping system on real farmland, and acts as a liaison between anxious entrepreneurs and growers who stand to benefit. “People with drones,” she says, “generally don’t know much about farms.”

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Martha Mobley[/mf_h2]

Franklin County, North Carolina

North Carolina State University

Years with extension: 28

“Ultimately we’re problem solvers,” explains Martha Mobley, offering a simple job description to encompass the myriad tasks she tackles. Among her most bizarre challenges: figuring out why horses developed kidney stones (bad hay), finding escaped pythons (under the house), and diagnosing cause of death in cattle (moldy sweet potatoes). “There’s something like that going on all the time,” she says.

Mobley, 57, also responds to wide-open queries – like “How can I make a living off my land?” by assessing the individual’s property and skill level, then advising on everything from acquiring dairy goats to cultivating vegetables.

While most ag agents tend to specialize, this one grew up on the diversified family farm she now runs, giving her decades of hands-on experience with organic produce, cows, pigs, sheep, and more. “Her breadth of knowledge is absolutely insane,” says Rebecca Larkin-Martinez, owner of Fort Clux Farm. “I’ll never understand where she gets her energy.”

Widowed when her husband passed away in 2013, Mobley is particularly passionate about support-ing other women. Recently, she launched a ladies-only forestry workshop called “Women in the Woods.”

Each September, Mobley personally hosts some 275 guests on her property for “Dinner in the Meadow,” a fundraiser that enables her to hand out small financial grants to area farmers. How on earth does Mobley find the time to produce such a massive benefit? That, she’ll tell you, is what vacation days are for.

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Adrian Card[/mf_h2]

Boulder, Colorado

Colorado State University Extension

Years with extension: 12

Adrian Card may have earned his master’s in agriculture from Colorado State, but his mediation skills rival those of any diplomat. “My job in Boulder County lies at the intersection of ag and politics,” says Card, whose community is embroiled in conflicts over irrigation management practices, GMOs, and organic-versus-conventional farming. “Right now, we’re dealing with great concern over nonorganic practices on public land,” he adds, referring to plots the government bought in the 1970s to guard against overdevelopment that it leases to farmers.

Recognizing that an informal atmosphere often fosters friendly communication, Card, 44, has begun hosting regular “Farmer Talk Tuesdays” at local microbreweries, where he moderates panels on a slew of agricultural issues. “Adrian tempers the extremes and keeps things balanced and level-headed,” says John Steiner, also a participant in Card’s nine-year-old “Building Farmers” education and mentorship program.

Michael Moss, who raises organic vegetables on government-owned land, consults Card, himself a former farmer, regarding matters even dirtier than politics. “Recently, Adrian met me in my greenhouse and talked for an hour about growing techniques, airflow, and irrigation,” Moss recalls. “Most extension agents are there to answer your questions, but Adrian is proactive and forward-thinking.”

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Jennifer Herrera[/mf_h2]

San Benito, Texas

Texas A&M AgriLife

Years with extension: 6

At the tender age of 25, Jennifer Herrera got a message from her office’s front desk: Someone had delivered a dozen roses with her name on them. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s nice!’” she recalls. “I expected a vase of pretty flowers, but to my surprise, I found a cardboard box full of long-stemmed roses that were crisp to the touch. Someone had dropped them off for me to inspect for disease.”

Perhaps Herrera should have known better, but the biology undergrad had just joined the extension office straight out of college. “When she came in, Jennifer didn’t know where to start,” says Chuck Malloy, president of the county’s association for master gardeners. “Now, her programs are so successful, other agents come to her for guidance.”

The 31-year-old, who has since earned her master’s in agricultural science from Texas A&M, credits her connection to the community for her effectiveness. Born and raised in Cameron County, Texas, Herrera hopes to improve the low-income food desert’s access to healthy, farm-fresh produce. “I work with home-owners and schools to teach people how to produce their own fruits and vegetables on a small scale,” she says. Herrera has fostered the start-up of 15 community gardens and arranges cooking demonstrations and classes on basic nutrition, crucial in an area with an obesity epidemic. “It’s too early to tell if we’re making a difference,” she admits. “But I’ve already noticed that people around here are much more willing to try new vegetables.”

[mf_h2 align=”left” transform=”uppercase”]Richard Kersbergen[/mf_h2]

Waldo, Maine

University of Maine

Years with extension: 29

Maine boasted 900 dairy farms when Richard Kersbergen joined one of the state’s 16 extension offices nearly three decades ago. Today, a mere 260 milking outfits remain in operation. Though the 58-year-old holds a master’s in animal nutrition, he thinks more about economics nowadays.”

I’d like to see these farms become financially viable again,” explains Kersbergen, “perhaps by switching to organic methods, improving forage quality, or introducing robotic milking systems.” To learn about the latter, he took a sabbatical in 2014 and traveled around the Netherlands, observing how small Dutch dairies use the machinery, blogging all the while to share the details with folks at home.

“He’s also an incredible resource when it comes to crops,” says Jean English of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association. “I’ve known Richard for 30 years, and I’ve seen him grow demonstration vegetable gardens and hold field days to share techniques like flame weeding.”

For Kersbergen, though, it always comes back to the cows. A few years ago, an area farmer reported strange skin lesions on a calf. Then another, 20 miles away, phoned about a similar condition. Kersbergen was mystified until his field studies on the first property revealed a large black spot underneath a tree. Turns out, the cow had taken shelter there during a thunderstorm, and what looked like a lesion was actually a burn. A charred tree on the second site confirmed that, in this case, lightning really did strike twice.