How Regional Food Hubs Shrink the Path from Farm to Fridge

Farmers gain markets they can count on, while consumers enjoy fresh food sourced locally. What’s not to love about regional food hubs?

How Regional Food Hubs Shrink the Path from Farm to Fridge

Farmers gain markets they can count on, while consumers enjoy fresh food sourced locally. What’s not to love about regional food hubs?

It had never occurred to Donna Williams, a former Manhattan investment banker with an MBA from Columbia University, that her professional trajectory might one day land her on a turnip truck—literally.

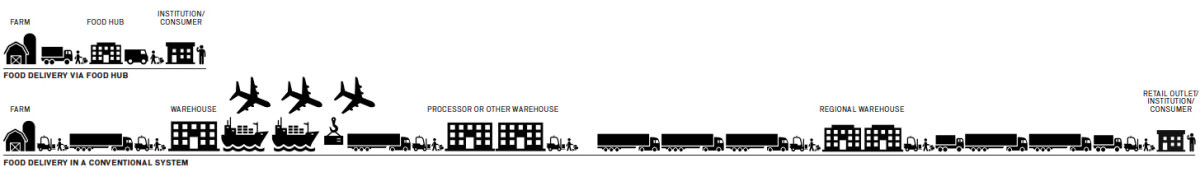

Then, in 2010, she was hired to prepare a feasibility study for a would-be agricultural incubator – a place for new farmers to train and share resources. Williams interviewed growers in and around the tiny hamlet of Athens, New York, where her parents owned a home, and heard the same complaint: Small farms with relatively low volumes of less-than-perfect produce found it impossible to win contracts from major retailers, and challenging to build a base of individual consumers. And while she understood that industrialized agriculture’s current distribution model racks up millions of earth-damaging food miles, Williams was surprised to learn that it also creates mountains of food waste – at every step in the chain, as fruits and vegetables travel from farm to warehouse to processor to local distribution center before reaching supermarket shelves (see “Shrinking the Distribution Chain,” below). The blame, she says, falls squarely on the shoulders of consumers, who prize convenience, low cost, and uniformity above all. “So long as consumer behavior stays the same, no new solution can do a meaningful job of fixing the problem.”

Williams decided to give it a go anyway, launching Field Goods four years ago. Her subscription-based service, located in Athens, operates like a CSA on steroids, connecting 80 farms to 3,000 customers. By taking on the role of intermediary – determining which products to include, drumming up demand, and delivering the goods to locations in New York and Connecticut – she relieves farmers of the burden of marketing and prods consumers to make better choices, without leaving a big carbon footprint.

Williams isn’t alone in her thinking. Regional “food hubs” – for-profit and nonprofit operations that manage the aggregation and distribution of food from area producers – are growing at an astonishing pace, according to a recent study by Michigan State University and the Wallace Center, in Arlington, Virginia. While large-scale aggregators like Organic Valley and Niman Ranch have been around for decades, 62 percent of the 300-plus hubs now in existence in the United States were formed during the past five years. Jeff Farbman, a senior program associate with the Wallace Center, calls food hubs “an astounding success,” responsible for “making farms more profitable, increasing acres in production, enabling farmers to achieve a better price and, in turn, to hire more workers.” Farbman points to “moral principles” (values related to sustainability, fair labor, and humane animal husbandry) and the sorts of personal relationships possible only in small supply chains as further reasons for the skyrocketing popularity of hubs.

To build her customer base, Williams pitched Field Goods to human resources departments as a wellness program. (“I mean, you can only do so many chair massages,” she says.) What began as a one-woman show – with Williams bagging all the produce, loading it into her dad’s un-air-conditioned 1994 Ford Taurus, and driving it around to offices and public libraries – now serves 500 workplaces and public drop-off points.

Williams aspires to keep each week’s selection, generally amounting to seven items (from a rotation of about 150, including some flash-frozen veggies), varied and surprising. A newsletter tucked into each bag and accessible online explains where and how each item was grown and offers suggestions for preparing it. Between the convenience and the value, says Williams – “sometimes when we price out our bags, it’s 30 percent less, relative to retail” – Field Goods has become “somewhat cultish.” Today, she pays nine full-time and 22 part-time employees, and she recently renovated an 18,000-square-foot cold-storage facility to accommodate her expanding business.

When Bob Knight, a former telecommunications executive, established Old Grove Orange a decade ago, it was with two goals in mind: to get back to the land and to build a local movement focused on sustainability. In the aftermath of 9/11, Knight, who had worked overseas for two decades, relocated from Saudi Arabia to the 67 acres in Redlands, California, where his family has farmed for four generations. The father of two came up with the idea of selling his fruits and vegetables to school districts as a way of achieving scale. “A 30-member CSA and a run of eight restaurants are never going to sustain a local food shed,” he says.

Knight, who now works with 27 other farms, attributes the success of Old Grove to the connections he’s established with school nutrition directors and the fact that all deliveries are done by members of the food hub. “We don’t believe in growing stuff and letting a distributor take it,” he says. “When that happens, you lose the customer relationship.”While friends at the farmers market laugh at Knight’s low prices, he says, sheer volume ensures profitability. “A nutrition director is like a restaurant that serves 20,000 meals a day. We only have to keep 26 customers happy, but they represent 1.5 million kids.”

In any case, Knight adds, it’s not just produce he’s selling. “It’s open space, heritage preservation, local jobs.” Old Grove occasionally sets up mini farmers markets at its member schools and lets students choose what they want to eat. “We turn it into a nutrition exercise.”

Philadelphia native Haile Johnston and his wife, Tatiana Garcia-Granados, stumbled upon the notion for their food hub almost by accident. In 2005 the pair accompanied a friend to a produce auction in the Pennsylvania countryside. “We picked up a paddle and started bidding,” Johnston recalls, “and ended up with 10 bushels of apples.” They paid less than $5 per bushel – as opposed to the $25 they typically shelled out in the city. “Farmers aren’t being paid fairly for what they’re producing,” Johnston recalls realizing at the time. “They’re selling it for less than the cost of the box.”

On the ride home, Johnston and Garcia-Granados, both graduates of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, figured there must be a way to get more money into farmers’ pockets. At the same time, they’d been debating how to direct healthier food to the low-income, predominantly African American residents of the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood, where the couple lead the East Park Revitalization Alliance, an organization with a focus on gardening and nutrition. Though affluent Philadelphians had long been enjoying local fare at restaurants and from farmers markets, Johnston says, “access to good food had not yet been democratized.”

With funding from the USDA, the two teamed with a third partner to launch Common Market in 2008. The nonprofit currently connects 75 farms with schools, hospitals, workplaces, and grocery stores in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. As more farmers come on board, says Johnston, who oversees a 70,000-square-foot facility and five refrigerated trucks, the number of people in underserved communities who benefit from their efforts continues to grow. Today Common Market serves 16 hospitals and 26 charter schools and reaches 1,100 members through Farm Share, a CSA program that coordinates twice-weekly deliveries in Philadelphia and its environs.

Johnston and Garcia-Granados believe that scale is essential to effect true change, so Common Market recently partnered with Sodexo to reach the corporation’s institutional buyers in the Northeast. And this year, the nonprofit expanded, establishing a branch of Common Market in Atlanta; the couple hopes it will be the first of many affiliates across the country. “We want to make local food in an institutional context the norm,” says Johnston, “to capture this surging opportunity.”

Shrinking the Distribution Chain

The products on your supermarket shelves may have traveled thousands of miles to get there, consuming fossil fuels and resulting in food waste along the way. By keeping things local, regional food hubs eliminate steps between a farmer’s field and consumer’s fridge.

The Food Hub Goes Global

The Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership (CGEP), founded in 2007 by Bill Clinton and Frank Giustra (the owner of this magazine), implements the food-hub concept on an international level – connecting small farms in the developing world with corporate buyers seeking large volumes of agricultural goods. In Haiti, the initiative established a business that built regional hubs where peanut growers deliver their harvests for sale to corporate partners. Once the farmers have been paid, any profits are put toward the construction of new hubs, thus ensuring the growth of the enterprise. The CGEP is working with fruit and vegetable farmers in Colombia to supply that nation’s largest grocery store chain, and recently announced a partner-ship with Unilever to connect the multinational with farmers around the world. “By reverse-engineering the need of global companies for a reliable supply of products at scale and to their quality specs,” says Giustra, “we can organize small farmers and build the supply chain to meet that need.”

Dan Sullivan is a freelance writer and garlic farmer based in southeast Pennsylvania.

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Dan Sullivan, Modern Farmer

January 13, 2016

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.