A Bitter Harvest: Inside Japanese-American Internment Camps During World War II

For the Japanese Americans interned during World War II, farming served as a tie to the past – and to the future.

A Bitter Harvest: Inside Japanese-American Internment Camps During World War II

For the Japanese Americans interned during World War II, farming served as a tie to the past – and to the future.

The Masumotos labored as hired hands, then went home to grow their own grapes, peaches, and plums on rented land. My grandparents, like many others, had been barred from buying property due to the discriminatory laws of the 1920s. But a thriving Japanese farm community persevered in California’s Central Valley. Most rented, some farmed under corporation names, many waited until their American-born children could finally plant deep roots. By the early 1940s, Japanese growers had established a large presence in the state’s produce and floral industries, dominating the markets in strawberries, celery, and peppers. Japanese Americans farmed more than 200,000 acres and accounted for 30 percent of California’s truck farmers.

Then World War II broke out, aiming venom at a people who looked like the enemy. The trajectory of a farm community was crushed, and an American dream shattered.

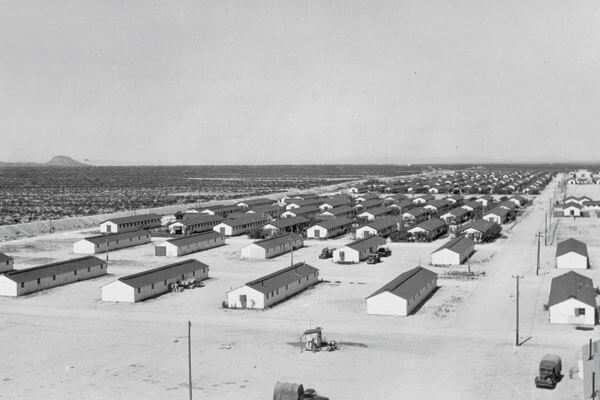

In February of 1942, President Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066, mandating that Japanese Americans be imprisoned in relocation camps in the nation’s interior. My family was forced to evacuate Fresno. Within a few weeks of receiving notice that summer, the Masumotos had sold their belongings, packed a few suitcases, boarded trains, and disembarked at a prison camp south of Phoenix, Arizona. They lived there, behind barbed wire and overseen by guard towers, for four years.

A stain on American history. A shame some never overcame. Many felt betrayed and became embittered. They internalized their anger, helpless and saddened that others had stood by and watched as they were stripped of their rights.

But in this dark moment of crisis, a handful of good neighbors emerged. They rose to the occasion, responding to the injustices before them. Some acts of kindness were simple and brief; others were long-term, bolstered by a fierce belief in doing the right thing. These were private acts that spoke loudly, especially in rural America, where conservative politics reigned.

By August, the grapes my family had been growing were a month away from harvest. My grandparents’ landlord offered pennies on the dollar for the crop and, a week before their forced exile, he kicked them off the farm to make way for new renters. Homeless, my father approached a nearby farmer. The neighbor felt bad that all he could offer was a barn. But that small gesture helped in a very difficult time: The Masumotos had shelter, even if just for a week. Not everyone shunned us and detested our faces.

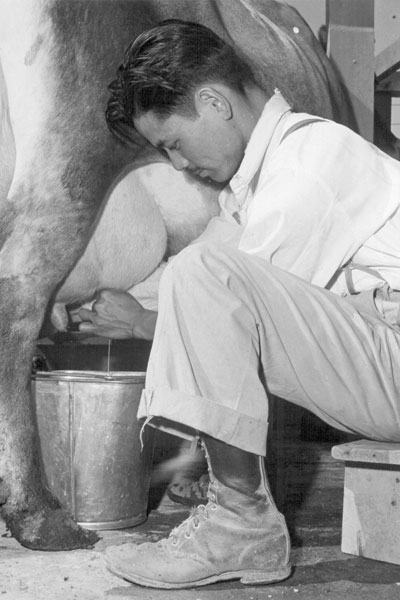

Even in the bleak environment of the internment camps, the spirit to work the land persevered.

The Hiyamas of nearby Fowler scrambled to find a way to protect the farm they owned. They met with a local man named Kamm Oliver, and with a handshake reached an understanding. “The right thing to do,” Oliver told me years later. He’d ignored the accusations of “Jap lover” and “traitor.” Oliver took care of the Hiyama vineyard like it was his own, sending annual checks for the raisin harvest, until the Japanese-American family returned. At one point, he and another neighbor drove from Fresno to the Gila River Relocation Center, south of Phoenix. Loaded in Oliver’s truck were furniture and other belong ings for the Hiyamas to use in their barracks. As Oliver drove deep into the Arizona desert, he wondered aloud, “Who could live in this god-forsaken place?”

In the early 1900s, a group of Japanese Americans had formed a farming association in Livingston, California. During the war years, a handful of white lawyers, bookkeepers, and office managers kept the group’s thousands of acres alive. These good neighbors regularly journeyed to the Granada Relocation Center, in Amache, Colorado, to consult with the incarcerated farmers and distribute profits. For a few Japanese-American farm communities, in the fog of war, a distant light could be seen.

Even in the bleak environment of the internment camps, the spirit to work the land persevered. It was about maintaining identity with resilience and hope. Growing food renewed a tie to something real: farming the dirt and feeding others. My dad was anxious to do something, “anything,” he said. Others thought it the best way to make the most of a bad situation.

Japanese-American farmers transformed the barren acres of Manzanar, in the California mountains; the high deserts of Heart Mountain, Wyoming; and the densely wooded areas of Jerome, Arkansas. My family worked the farms, dairy, and produce-shipping operations at Gila River Relocation Center, in Rivers, Arizona. “We grew vegetables for all the other camps,” explained one farmer there. “They couldn’t get Japanese food, so we grew daikon for everyone.”

At the end of the war, some Japanese Americans abandoned their rural pasts, the lineage of farming broken. But others returned to California. As my father told me later, “We had no other place to go.” A fortunate few reclaimed farms and property, transitions made possible by the commitment of others who took care of their neighbors: quiet yet brave deeds, too-often invisible acts of courage.

The internment of Japanese-American farmers changed economic and social structures. In addition to those who never went back home were farmers who lost opportunities to expand. The nightmare of loss compelled families to pursue safe professions for their children, to send them off the farm and away to college. Shame wounded an entire generation, the spirit of entrepreneurship destroyed. It took years for my family to make a fruit label with our own name: Somehow it seemed easier to remain invisible.

It’s impossible to separate the past from the peaches and nectarines and raisins that I grow today. People don’t just buy my produce; with each peach, they consume a little of my family’s past. The taste can be bittersweet.

These portraits depict farmers at Arizona’s Gila River Relocation Center.

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/japanese-americans-tomato-seedlings.jpg” alt=”george nagamatsu” title=””]The family of George Nagamatsu, here with tomato seedlings, had owned a 300-acre farm in Santa Ana, CA.[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/japanese-americans-spinach.jpg” alt=”momayo yamamoto spinach” title=””]Momayo Yamamoto, formerly of Fresno, harvests spinach.[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/japanese-americans-flower-nursery.jpg” alt=”paul s goya” title=””]Paul S. Goya, who had run a flower business in Sierra Madre, CA, oversaw the internment camp’s flower nursery.[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/japanese-americans-daikon.jpg” alt=”momoyo yamamoto daikon” title=””]Momoyo Yamamoto, formerly of Fresno, harvests daikon. [/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/japanese-americans-nappa-plants.jpg” alt=”u shine” title=””]U. Shine, holding Nappa plants, had worked at a vineyard in Kingsburg, AZ.[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/japanese-americans-onion-plants.jpg” alt=”s hanasaki” title=””]Vegetable-seed specialist S. Hanasaki, who owned a seed business in San Jose, CA, examines onion plants ready to be harvested for seed.[/mf_image_grid_item]

David Mas Masumoto grows organic peaches on a farm near Fresno, CA. He is the author of Epitaph for a Peach and Wisdom of the Last Farmer (2009).

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by David Mas Masumoto, Modern Farmer

October 13, 2015

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

The biggest issue of this period is exploitation, rural imperialism as much as I can change the way people are treated. Moreover, these rural communities as a whole are filled with social experiences where even in times of xenophobic war ties between neighbours areined. Another point to highlight is that the text mentions a lot of the moral issue, doing the right thing, “because they were good people”, but it forgets that the practical materiality of things does not work with this bias. The care of the fellow is important for the social survival itself and also of the rural… Read more »