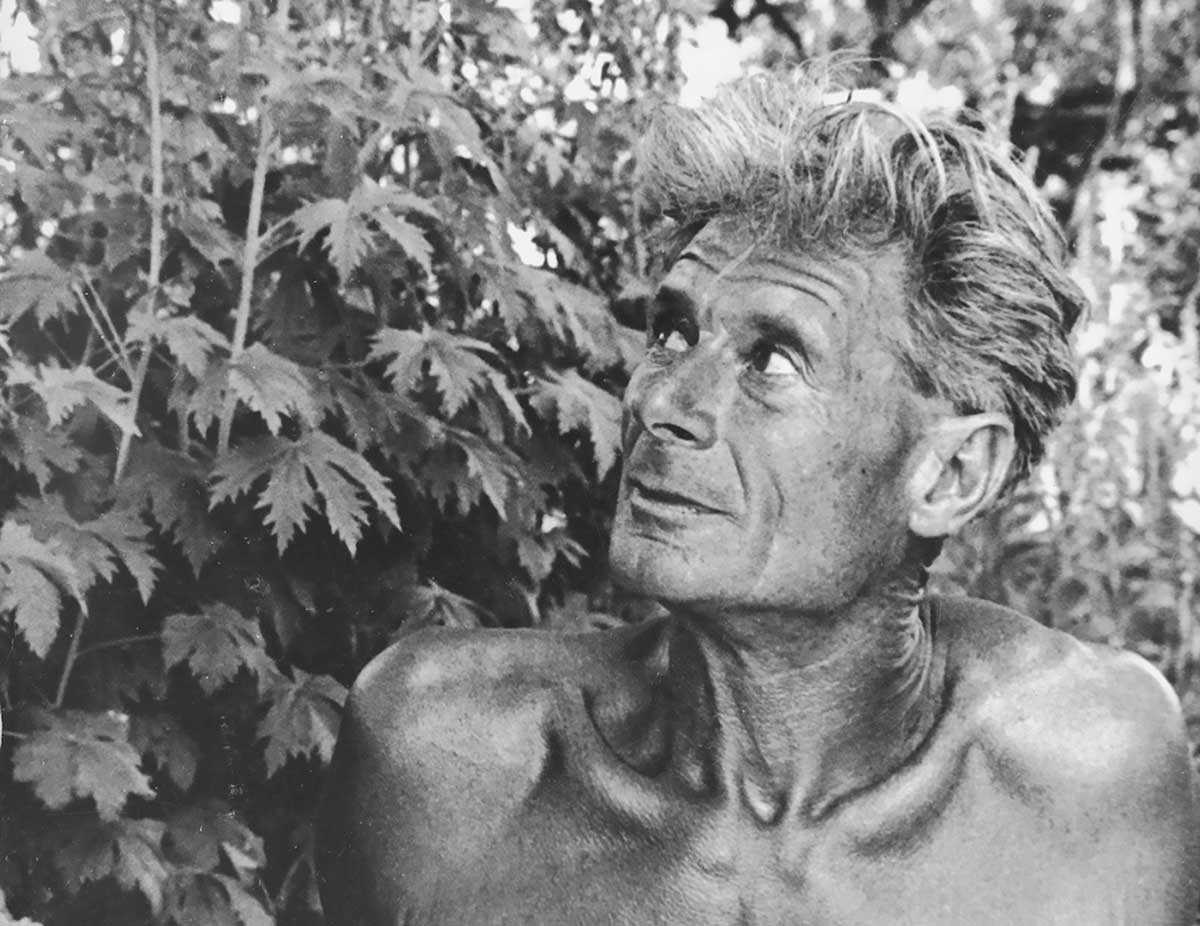

Meet Alan Chadwick, The High Priest of Hippie Horticulture

Biodynamic pioneer Alan Chadwick turned America on to radical growing methods – influencing everyone from Alice Waters to winemakers Fetzer and Frey. So how come you’ve never heard of him?

Meet Alan Chadwick, The High Priest of Hippie Horticulture

Biodynamic pioneer Alan Chadwick turned America on to radical growing methods – influencing everyone from Alice Waters to winemakers Fetzer and Frey. So how come you’ve never heard of him?

When Alan Chadwick descended on the campus of the fledgling University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1967, it was as if a character had stepped right out of the pages of English literature. A tall and striking man with a shock of white hair and a regal bearing that bespoke his privileged upbringing, Chadwick was also a Shakespearean actor who had trained in London under the same teacher as Laurence Olivier and Harold Pinter.

Chadwick came to Santa Cruz on the recommendation of Freya von Moltke, the widow of a leader in the German resistance against Hitler. Her husband, Count Helmuth von Moltke, was arrested, accused of treason, and hanged. But before Helmuth was executed, he sent word to his wife requesting that she make a place where young people could learn about creation in a world of destruction. The countess, often described as Chadwick’s muse, may have had that request in mind when she mentioned his name to Paul Lee, a UCSC philosophy professor who had pitched the idea of developing a teaching garden to the school’s chancellor.

Chadwick arrived on campus without so much as a salary or official position. He simply began digging – 14 hours a day, seven days a week – on a steep and barren hillside of chaparral and poison oak. Within a year, he had transformed that hillside into a vibrant and abundant garden of flowers, vegetables, and fruit trees. Young men and women were soon drawn to work with this temperamental perfectionist who cared about his garden above all else.

One of them, Nancy Lingemann, recalls, “I’d lost all interest in school. The only thing I wanted to do was garden.” Lingemann ditched most of her classes to follow Chadwick and went on to create a wedding-flower business, called Flower Ladies, in the hills above the university.

Chadwick used the power and language of theater to proselytize on behalf of the biodiversity of plants and the sacrament of nature. He gave group lessons in mime, mien, and deportment, insisting his students stand up straight, carry themselves with dignity, and enunciate clearly. They were expected to memorize the Friar’s speech from Romeo and Juliet on the power of medicinal herbs. Above all, they had to embrace the ethos of hard work.

“His garden had a presence – like Alan himself,” says Stephen Decater, who labored in the UCSC garden almost the entire time Chadwick was there and is now the owner, with his wife, Gloria, of Live Power Community Farm in Covelo, California. “It wasn’t just a collection of plants. It was a living being that spoke through the plants.”

Chadwick’s mother, Elizabeth, was a follower of Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian philosopher and social scientist responsible for Waldorf education and biodynamic agriculture. She hired him one summer to tutor Alan and his older brother, Seddon, on horticulture and the finer points of composting. Steiner’s teachings took root, as many decades later Chadwick told an apprentice, “I’ll be 70 years old. There are seeds still sprouting in me today from things he told me.”

Chief among them? Double-digging, a labor-intensive technique that’s one of the key components of biodynamic agriculture. Chadwick was a stickler for this method, which involves removing the topsoil down to the level of the subsoil, which is then broken up, overlaid with manure or compost, and mixed in with topsoil. The method proved integral to returning the UCSC hillside to fertility.

“The site had great visibility and sun exposure, but there’d been a road dug into it,” remembers Jim Nelson, whose father was disappointed when he dropped out of college to work full time with Chadwick. “Sometimes you’d have to pick-axe through the crust.”

To Chadwick soil was alive and never to be confused with dirt. He once told a group of apprentices, “Everyone thinks that soil is dirt, is there forever, that you can tread on it, jump on it, bite it, kick it, eat it, throw stones on it, do anything you like on it, and it is the same in the fall as it is in the spring, and the same in the winter as it is in the summer. That is completely untrue.”

What Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters were to the psychedelic culture of the 1960s, Chadwick and his band of diggers were to food and gardening.

School administrators didn’t know what to make of him. Parents complained that he was a Pied Piper, stealing away promising students like Nelson, today the owner of Camp Joy, a small organic farm in nearby Boulder Creek. “I don’t think the university ever realized what they had in Alan,” Nelson says. “He had no credentials. He was an artist and a teacher, in the deepest sense of the word, though he didn’t consider himself a teacher. He pointed in directions, and it was up to you to find your place in the natural world.”

Chadwick also had a savage temper and could be his own worst enemy. Paul Lee, his great champion at Santa Cruz, detailed in his 2013 book, There Is a Garden in the Mind: A Memoir of Alan Chadwick and the Organic Movement in California, the kind of “psychic vomit” Chadwick was capable of spewing. Lee described a kind of Dr. Doolittle, a man so gentle and in tune with nature that birds would land on his shoulder. But cross him, and all hell broke loose. “You either stood up to him or were broken by him,” Lee wrote. Chadwick once feuded with the young family living in the apartment above him. Lee recounts, “If they flushed the toilet after six, the sound of the water coursing through the pipes drove him nuts and set him off. He took to breaking wine bottles in the backyard after pounding on the ceiling and yelling his head off. They thought he was crazy.”

Deborah Madison, founding chef of the groundbreaking vegetarian restaurant Greens, in San Francisco, and a bestselling cookbook author, was a student at UCSC when Chadwick’s garden was in full splendor. During her first visit there, Chadwick screamed at her from clear across the garden. He accused her of stepping on a raised bed – something that Madison, a farm girl born and raised, would never do. “I don’t know how he could even have seen me from that distance,” she says. “I never went back.”

The Santa Cruz garden became a magnet for luminaries, drawing the composer John Cage, who made a pilgrimage to meet Chadwick and forage for wild mushrooms in the surrounding forest. Robert Rodale, the organic farm and garden publisher, popped in to see what Chadwick was up to, as did the farmer-poet Wendell Berry. After touring the garden, Joseph Williamson, the then-editor of California’s influential Sunset magazine, was so affected that he overnight became a voice for organic gardening.

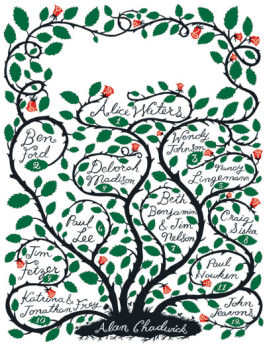

Today, many consider Chadwick one of the founders of the organic food movement. His garden at UCSC has evolved into the Center for Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems, a nucleus for research and education in the field. His acolytes have fanned out across the country, applying his methods and philosophy to a network of organic and sustainable farms. Even chef Alice Waters, founder of Chez Panisse, has cited him as a seminal influence. What Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters were to the psychedelic culture of the 1960s, Chadwick and his band of diggers were to food and gardening.

Chadwick left Santa Cruz in early 1972, driven out in what Lee and others have portrayed as an epic struggle for the heart of the university. It was a battle between reductionist material science and spiritual nature. Shortly after a UCSC chemist submitted that “the garden has done more to ruin the cause of science on this campus than anything else,” Chadwick was gone.

Within a few months, he’d been named head gardener of Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, just north of San Francisco. He was again accompanied by a coterie of dedicated apprentices; his dramatic tendencies went with him, too. Wendy Johnson, who lived and studied at Green Gulch from 1975 to 2000, described Chadwick’s antics in her 2008 book, Gardening at the Dragon’s Gate: “He wailed at top volume each time the wooden sounding block was struck for meditation and faithful Zen students mindfully put down their tools and headed calmly for the meditation hall. ‘Look at this – look at this!’ Alan ranted and seethed. ‘Perfectly able-bodied young men and women running to the atavistic sound of wood beating on wood. Running without shame, and leaving an old man like me to work alone in the garden!’ ”

Chadwick’s Green Gulch tenure proved even shorter than the one in Santa Cruz, largely because he lacked patience for those Buddhist apprentices. “He couldn’t fathom why we’d just go to meditation when there was work to be done,” recalls Deborah Madison, who had moved there to study Zen Buddhism after graduating from UCSC in 1968.

He was next invited to manage the Round Valley Garden Project, in Covelo, California. Widely regarded as Chadwick’s most fully realized garden, the enchanted property boasted vibrant poppies and his favorite heirloom roses.

Everything had to be done by hand. It was how he had cleared the four acres of Santa Cruz hillside, working with nothing more mechanized than a British Bulldog spade and fork. One of his students, John Jeavons, who wrote the influential How to Grow More Vegetables, in 1979, introduced the tools to Paul Hawken, who would later popularize them with his company Smith & Hawken.

Chadwick’s ardent opposition to all forms of mechanized farming never waned. In 1978, at what would be his final garden, in a spiritual community in New Market, Virginia, he saw a woman trimming a box hedge with electric clippers. He strode over and yelled at her to quit – which she did, instantly, dropping the clippers and running away, the evil device still writhing on the ground.

He experimented with many ways to create compost and, in each of his gardens, always had numerous piles burning at any given time. One might include aged dairy-animal manure, while another derived from plants. On occasion, he used ingredients included in preparations learned from Steiner that are meant to regenerate the soil and strengthen the earth’s life forces.

Steiner’s preparations, which lie at the heart of biodynamic agriculture, famously include a cow horn stuffed with manure and buried in soil throughout the winter months. After the manure ferments, it is dug out and a small amount stirred in water – first in one direction, then in another, before it’s sprayed onto the soil.

Craig Siska, who apprenticed to Chadwick in Virginia, pored over Steiner’s esoteric 1924 lectures about the preparations and couldn’t make heads or tails of them. Finally, he asked the master gardener if he intended to apply the preparations to the Virginia garden. Chadwick’s reply: a firm no.

Siska recalls him saying, “When people come to this place and see the beauty and magic and robustiousness, I don’t want them to attribute it to potions. The garden comes out of the soul of the gardener and that person’s obedience and reverence for the laws of nature.”

In fact, according to Siska, Chadwick was taken to task by biodynamic practitioners for his failure to use the preparations. On one occasion, a group of Steiner devotees traveled to Virginia from their headquarters in Spring Valley, New York, in search of a meeting with Chadwick. “He avoided them,” Siska says. “He believed they put Steiner in a box, that it was all dogma, that they do everything by rote.”

Chadwick was in Virginia just over a year before the community disbanded and he returned to California. He was 70 and dying of prostate cancer when the Buddhists at Green Gulch welcomed him back. Though gaunt and weakened, it wasn’t long before he agreed to deliver weekly bedside talks to a small and select audience of future food and garden gurus: Alice Waters, Wendy Johnson, Deborah Madison.

By the time he died, in May 1980, Chadwick stood at the head of a lineage, his students having established some of the best organic farms and gardens in California and throughout the country. Even so, he expressed regret that he wasn’t the teacher he would have wished. “I have never been taught to be a teacher, and I know I’m impossible,” he confided to Siska.

Thirty-five-years later, Nancy Lingemann thinks of her teacher at least once a day. On a recent morning, she was in her greenhouse transplanting snapdragons when she heard his voice in her head: “Prick out the tiddlers,” it said, using an English term for a runt. “Don’t leave out the little ones just because they look weak. Very often they’re the rare color; they just need more time to grow.”

Lingemann smiled at the memory. “I will treasure forever what he gave me. It was direct transmission. It was precious, and we knew it was precious.”

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/alan-chadwick-covelo1.jpg” alt=”” title=””]Chadwick walks between protégés Warren Pierce (left) and Richard Joos in Covelo, CA. Courtesy of the Alan Chadwick Archive[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/alan-chadwick-shakespeare1.jpg” alt=”” title=””]A 1948 head shot shows the Shakespearean actor in full costume. Courtesy of Paul Lee[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/alan-chadwick-bulldog1.jpg” alt=”” title=””]Chadwick totes his Bulldog spade, later made famous by Smith & Hawken. Courtesy of CASFS; UC Santa Cruz[/mf_image_grid_item]

[mf_image_grid_item src=”https://modernfarmer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/alan-chadwick-digging1.jpg” alt=”” title=””]Chadwick, in the early ’70s, instructs UC Santa Cruz interns. Courtesy of CASFS; UC Santa Cruz[/mf_image_grid_item]

Sara Solovitch is the author of Playing Scared: A History and Memoir of Stage Fright (2015)

Follow us

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Want to republish a Modern Farmer story?

We are happy for Modern Farmer stories to be shared, and encourage you to republish our articles for your audience. When doing so, we ask that you follow these guidelines:

Please credit us and our writers

For the author byline, please use “Author Name, Modern Farmer.” At the top of our stories, if on the web, please include this text and link: “This story was originally published by Modern Farmer.”

Please make sure to include a link back to either our home page or the article URL.

At the bottom of the story, please include the following text:

“Modern Farmer is a nonprofit initiative dedicated to raising awareness and catalyzing action at the intersection of food, agriculture, and society. Read more at <link>Modern Farmer</link>.”

Use our widget

We’d like to be able to track our stories, so we ask that if you republish our content, you do so using our widget (located on the left hand side of the article). The HTML code has a built-in tracker that tells us the data and domain where the story was published, as well as view counts.

Check the image requirements

It’s your responsibility to confirm you're licensed to republish images in our articles. Some images, such as those from commercial providers, don't allow their images to be republished without permission or payment. Copyright terms are generally listed in the image caption and attribution. You are welcome to omit our images or substitute with your own. Charts and interactive graphics follow the same rules.

Don’t change too much. Or, ask us first.

Articles must be republished in their entirety. It’s okay to change references to time (“today” to “yesterday”) or location (“Iowa City, IA” to “here”). But please keep everything else the same.

If you feel strongly that a more material edit needs to be made, get in touch with us at [email protected]. We’re happy to discuss it with the original author, but we must have prior approval for changes before publication.

Special cases

Extracts. You may run the first few lines or paragraphs of the article and then say: “Read the full article at Modern Farmer” with a link back to the original article.

Quotes. You may quote authors provided you include a link back to the article URL.

Translations. These require writer approval. To inquire about translation of a Modern Farmer article, contact us at [email protected]

Signed consent / copyright release forms. These are not required, provided you are following these guidelines.

Print. Articles can be republished in print under these same rules, with the exception that you do not need to include the links.

Tag us

When sharing the story on social media, please tag us using the following: - Twitter (@ModFarm) - Facebook (@ModernFarmerMedia) - Instagram (@modfarm)

Use our content respectfully

Modern Farmer is a nonprofit and as such we share our content for free and in good faith in order to reach new audiences. Respectfully,

No selling ads against our stories. It’s okay to put our stories on pages with ads.

Don’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. We understand that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarize or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

Keep in touch

We want to hear from you if you love Modern Farmer content, have a collaboration idea, or anything else to share. As a nonprofit outlet, we work in service of our community and are always open to comments, feedback, and ideas. Contact us at [email protected].by Sara Solovitch, Modern Farmer

August 17, 2015

Modern Farmer Weekly

Solutions Hub

Innovations, ideas and inspiration. Actionable solutions for a resilient food system.

ExploreExplore other topics

Share With Us

We want to hear from Modern Farmer readers who have thoughtful commentary, actionable solutions, or helpful ideas to share.

SubmitNecessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and are used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies.

I met Maestro in Covelo. I was in charge of the Back 40 Acres Community Farm in East Palo Alto/Menlo Park. I apologized for using a tractor, and I brought him a sample of the adobe soil that we dealt with. We also had many seniors gardening. Double digging was impractical. Al was OK with it, mainly because we began to grow organically. He had been an officer in the Royal Navy in WW2. He spoke with me as a fellow “commander” as I managed the largest one-site community garden in California at that time. I use a synthesis of… Read more »

I worked under Alan in New Market, Va and at the end of his life there his lectures were powerful as he seemed to sense the end was near. Working in that garden and learning from his protoges was transformational. Later I worked at Green Gulch Farm and the garden created by one of his Covelo students, Skip Kimura. This was a beautiful article, thank you for writing it!

Double-digging is not a feature of Biodynamic agriculture. It’s a feature of French-intensive agriculture. Also I can’t find any evidence that Chadwick was schooled by Steiner. He attended courses yes, but first encountered philosopher during Steiner’s speaking tours in London in the early 1920’s