These new agrihoods have the potential to influence suburban life for decades to come.

Though the trend is new, the idea is an old one. From Frederic Law Olmsted’s faux-pastoral Riverside to the nostalgic, Disney-built town of Celebration, suburbs have always represented cultural aspiration more than reality. And like others before them, life in these agrihoods is more about the idea of living on a farm than the reality of it. Though residents reap the benefits of the agricultural life in the form of bucolic views and fresh meat and produce, their heirloom tomato patches, citrus groves and chicken coops are mostly tended by salaried farm managers.

Despite all this, the very existence of the agrihood trend is a powerful message that farm-to-table dining and environmental sustainability have become more than just buzzwords. They’ve become so deeply entrenched in our society that developers are using them to sell a lifestyle. And by looking at the legacy of the most influential planned communities of America’s past, it seems very possible that, like these neighborhoods before them, agrihoods have the potential to also shape the suburbs of the future.

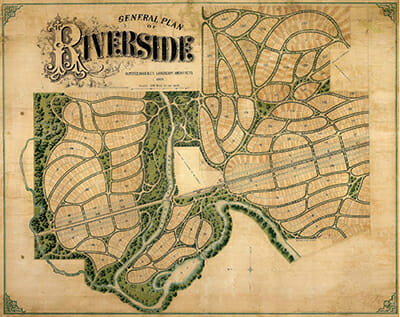

[mf_h5 align=”center” transform=”uppercase”]Riverside, Illinois[/mf_h5]

America’s wealthy and fashionable once lived in city centers, but the early- to mid-nineteenth century saw a huge influx of immigrants and factories, which made cities more dingy, disease-ridden and unsafe. The upper classes fled to the country, but not too far — thanks to technological advances like the expansion of commuter rail in the 1850s, they could still participate in the cultural and economic life of the city while living in park-like communities that were America’s first suburbs.

In 1869, the famous Central Park designers Frederic Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were hired to create Riverside on a tract about a half hour train ride from Chicago. The duo’s pastoral vision became the nation’s first planned community. They engineered the now-common curved suburban streets to make the place seem more rural; planted nearly 80,000 trees and shrubs for shade and visual disparity; and invented the front yard by dictating that all houses must be at least 30 feet from the road. Their resulting community lay somewhere between city and country, and is still one of the more affluent suburbs of Chicago.

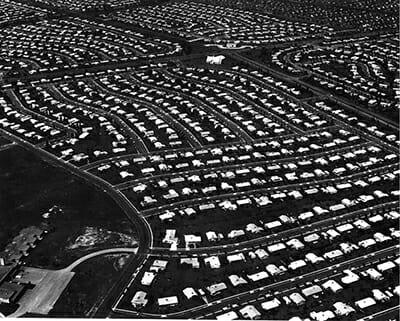

[mf_h5 align=”center” transform=”uppercase”]Levittown, New York[/mf_h5]

Suburbs changed in October 1947, the month that 300 families moved into Levittown, Long Island. The housing tract, created to provide affordable housing to World War II veterans and their families, was the first to use assembly-line tactics and pre-fabricated pieces to build houses in a hurry. This brought home prices down and, thanks also in part to a booming postwar economy, homeownership became feasible for many American families. The number of Americans who owned their own homes rose by 30 percent between 1940 and 1970.

If Riverside appealed to its wealthy residents because of its countryside vibe, Levittown and other developments like it provided normalcy and domesticity to families that had been torn apart during the war. Life wasn’t all Mad Men-esque bleakness and despair, either. People seemed happy enough, reported sociologist Herbert Gans, who lived in Levittown, New Jersey for two years and chronicled his experience in The Levittowners. “[In the suburbs], morale goes up, boredom and loneliness are reduced, family life becomes temporarily more cohesive, social and organizational activities multiply, and spare-time pursuits are [… ] concentrated on the house and yard,” he wrote.

[mf_h5 align=”center” transform=”uppercase”]Celebration, Florida[/mf_h5]

If you’ve ever walked down Main Street, U.S.A. in Disneyland or Disney World and thought, I wish I could live here, the Disney Corporation has been providing you with a chance since 1996. Celebration, Florida, just outside of Orlando, is the town that Disney built. From the outset, Celebration promised more than just a peaceful escape from the city, like Riverside, or a cozen haven for the middle class, like Levittown: It sold itself as a chance for a small town life that most only knew from movies. Early ads touched on fireflies, porch swings, grocery boys, Sunday morning cartoons and neighborly relations. Artificial leaves were dropped on Main Street during the fall; artificial snow in the winter.

Celebration was one of the most prominent examples of the growing New Urbanism: walkable suburbs built around a downtown. Like Gans before him, sociologist and NYU professor Dr. Andrew Ross took a year’s sabbatical to live in Celebration. His resulting book, The Celebration Chronicles, told the story of a town that had all the complications of real life underneath the Disney veneer. His first day in town, his neighbor told him “the pixie dust wears off quickly here,” and he quickly learned that the perfect houses Disney constructed were more like shoddily constructed stage sets.

Still, he found that the town had developed a community and sense of self, which persevered despite the weird Disneyficiation of everything. With their self-conscious lifestyle engineering, agrihoods owe as much to Celebration as to Riverside. Their influence on American culture is just beginning.

[mf_h5 align=”center” transform=”uppercase”]Fordlandia, Brazil[/mf_h5]

Cars need tires, and tires need rubber, and automobile baron Henry Ford didn’t have enough of it. In the early 20th century, he gathered together a group of workers and built Fordlandia, a community in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil next to a rubber farm he’d developed.

It was a spectacular failure. Though residents of Fordlandia imported the trappings of the Michigan suburban lifestyle, including swimming pools, square dances, golf courses, and American foods like hamburgers, they never really stuck in the Amazon jungle (it probably didn’t help that Ford imposed his own morals onto the town, banning booze). Natural predators preyed on the rubber trees. He gave the whole endeavor up after a few years. Nevertheless, Fordlandia might well have been the first planned agrihood — and as the still-empty buildings in Brazil will attest, a cautionary tale that once land is converted into suburbs, it’s hard to change it back.